Abstract

Herbivore-induced plant defences influence the behaviour of insects associated with the plant. For biting–chewing herbivores the octadecanoid signal-transduction pathway has been suggested to play a key role in induced plant defence. To test this hypothesis in our plant—herbivore—parasitoid tritrophic system, we used phenidone, an inhibitor of the enzyme lipoxygenase (LOX), that catalyses the initial step in the octadecanoid pathway. Phenidone treatment of Brussels sprouts plants reduced the accumulation of internal signalling compounds in the octadecanoid pathway downstream of the step catalysed by LOX, i.e. 12-oxo-phytodienoic acid (OPDA) and jasmonic acid. The attraction of Cotesia glomerata parasitoids to host-infested plants was significantly reduced by phenidone treatment. The three herbivores investigated, i.e. the specialists Plutella xylostella, Pieris brassicae and Pieris rapae, showed different oviposition preferences for intact and infested plants, and for two species their preference for either intact or infested plants was shown to be LOX dependent. Our results show that phenidone inhibits the LOX-dependent defence response of the plant and that this inhibition can influence the behaviour of members of the associated insect community.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Insects can use herbivore-induced plant chemicals as cues during host selection (Bruinsma and Dicke 2008; D’Alessandro and Turlings 2006; Schoonhoven et al. 2005). Both herbivores and their carnivorous natural enemies can use information on the infestation status of plants to their own benefit. Carnivores search for plants infested with their host or prey, while most herbivores prefer uninfested plants, avoiding oviposition on plants that are conspicuous to their enemies and might harbour herbivorous competitors (Dicke 2000; Dicke and Vet 1999; Schoonhoven et al. 2005; Turlings et al. 1990). However, in some cases, oviposition on plants infested with heterospecific herbivores can be advantageous, because it can decrease the searching efficiency of their enemies (Shiojiri et al. 2002). Infestation of a plant with a herbivorous insect leads to induced responses that may drastically change interactions of the plant with community members over longer time periods (Kessler and Baldwin 2004; Poelman et al. 2008a, b; Van Zandt and Agrawal 2004). Understanding which mechanisms underlie such induced responses allows the experimental manipulation of these responses in order to investigate plant phenotypic plasticity in the context of community ecology (Kessler and Baldwin 2002).

The octadecanoid pathway has been shown to play an important role in plant responses to caterpillar damage (e.g. Arimura et al. 2005; De Vos et al. 2005; Dicke and Van Poecke 2002; Kessler and Baldwin 2002; Van Poecke 2007). Lipoxygenase (LOX) is a key enzyme in this pathway and is induced by wounding. The conversion of linolenic acid into its 9- and 13-hydroperoxides is catalysed by 9- and 13-LOXs (Feussner and Wasternack 2002). The hydroperoxides are subsequently converted to aldehydes and oxoacids. Products derived from 13(S)-hydroperoxy linolenic acid can be further transformed by several enzymes to eventually produce jasmonic acid (JA) or, when mediated by hydroperoxide lyase, to the green leaf volatile (Z)-3-hexenal, and subsequently to (Z)-3-hexen-1-ol and (Z)-3-hexen-1-yl acetate (Fig. 1; Kessler and Baldwin 2002; Koch et al. 1999). LOX-deficient plants are more susceptible to herbivore attack (Halitschke and Baldwin 2003; Kessler et al. 2004; Royo et al. 1999). Furthermore, caterpillar damage upregulates the expression of LOX genes in plants such as Arabidopsis thaliana, tobacco and tomato (Bell et al. 1995; Halitschke and Baldwin 2003; Heitz et al. 1997), as well as in the plant we studied, Brassica oleracea (Zheng et al. 2007). The redox-active compound 1-phenyl-pyrazolidinone (phenidone) is known to inhibit the activity of LOXs (Fig. 1; Cucurou et al. 1991; Engelberth et al. 2001; Koch et al. 1999), by reducing the active form of LOX to an inactive form. Therefore, phenidone is an effective inhibitor of the octadecanoid pathway, and we hypothesised that it would inhibit the plant’s induced defence system (Dicke and Van Poecke 2002) and therefore affect its interactions with the associated insect community.

Indeed, several studies found that in Lima bean plants (Phaseolus lunatus) phenidone treatment inhibited the emission of several volatiles upon treatment with cellulysin, a fungal elicitor of the octadecanoid pathway (Engelberth et al. 2001; Koch et al. 1999; Piel et al. 1997). Besides plant volatile emission, extra floral nectar (EFN) secretion is also affected by LOX inhibition. Exogenous application of phenidone resulted in a suppression of EFN secretion of nine Acacia species, but treatment with JA could restore the EFN secretion (Heil et al. 2004). The inhibitory effect of phenidone is not restricted to LOXs from plants, it also inhibits lipo- and cyclooxygenases from animals (Cucurou et al. 1991; Hlasta et al. 1991; Li et al. 2008).

In the present study, we tested the hypotheses that: (1) inhibition of LOX, as the primary catalytic step in the octadecanoid pathway, will lead to reduced herbivore-induced plant defence in terms of oxylipin accumulation; (2) a reduced level of direct plant defence will reduce avoidance behaviour of herbivorous insects attacking the plant; (3) a reduced level of indirect plant defence will affect the emission of herbivore-induced plant volatiles and reduce the attraction of carnivorous insects. We studied the interactions between B. oleracea, three biting–chewing specialist herbivores, i.e. Plutella xylostella, Pieris rapae and Pieris brassicae, and the endoparasitoid Cotesia glomerata, a natural enemy of the latter two species. To achieve LOX inhibition, we applied phenidone as a specific inhibitor.

Materials and methods

Insect and plant material

Brussels sprouts plants, Brassica oleracea L. var. gemmifera cv. Cyrus, were grown from seeds in plastic pots (11 × 11 cm) in a greenhouse at 20–28°C, 40–80% relative humidity (RH) and a 16:8-h light:dark (L:D) photoperiod (>200 μmol m−2 s−1 photosynthetically active radiation; QMSW-SS quantum meter; Apogee Instruments, Logan, Utah). The large cabbage white, Pieris brassicae L., the small cabbage white, Pieris rapae L. (Lepidoptera: Pieridae), and the diamondback moth Plutella xylostella L. (Lepidoptera: Yponomeutidae) were reared on Brussels sprouts plants in a climatised room at 20–22°C, 50–70% RH and a 16:8-h L:D photoperiod. The parasitoid wasp Cotesia glomerata L. (Hymenoptera: Braconidae) was maintained on P. brassicae feeding on Brussels sprouts plants in a greenhouse at 22–24°C, 50–70% RH and a 16:8-h L:D photoperiod. Adult wasps emerged in a cage without any plants or hosts (and were therefore designated naïve with respect to cues related to herbivore-infested plants), and were provided with honey and kept at the same climatic conditions as the rearing until use in the experiments.

Plant treatments

Six- to 7-week-old plants, with eight to nine leaves, were sprayed with 15 ml of a 2 mM aqueous solution of the inhibitor phenidone containing 0.1% of polyoxy-ethylenesorbitan monolaurate (Tween 20) (both obtained from Sigma–Aldrich, St Louis, Mo.) until run-off. After 30 min, 15 P. brassicae or P. rapae second-instar larvae were placed on the three middle leaves of the plant i.e. five caterpillars per leaf. To test the effect of this inhibitor treatment we used two control treatments: plants that were treated with a 0.1% Tween 20 solution and after 30 min infested with 15 P. brassicae or P. rapae larvae to induce a full volatile blend, and plants that were treated solely with the inhibitor solution. After 24 h at 22–24°C, 50–70% RH and a 16:8-h L:D photoperiod, the plants were used in the bioassays.

Oviposition preference of P. rapae and P. brassicae

Adult butterflies emerged from pupae in a 67 × 100 × 75-cm cage in a greenhouse compartment at 22–24°C and 50–70% RH. Artificial light (SON-T sodium vapour lamps, 500 W; Philips, The Netherlands) was used in the cage from 8.00 a.m. until 2.00 p.m. in addition to natural daylight. The butterflies were provided with a 10% sucrose solution to feed on and a Brussels sprouts plant for oviposition. One day before an experiment started, one male and one female butterfly were introduced into a 67 × 50 × 75-cm experimental oviposition cage. They were provided with sucrose solution to feed on. Two leaves, freshly excised from plants belonging to two different treatment groups were introduced into the cages at 8.30 a.m. and the butterflies were allowed to oviposit until 2.00 p.m. Subsequently, the leaves were removed from the cages and the number of eggs on each leaf was counted. The experiment was performed using ten butterfly pairs per day and each treatment was replicated 20–30 times. Each day, new pairs of butterflies and new plants were used.

First, leaves infested with caterpillars were tested against uninfested leaves, to test whether the butterflies discriminated between them. The leaves were infested with larvae of the same species as the butterflies whose behaviour was investigated. Subsequently, for P. brassicae butterflies we tested: (1) (locally) infested leaves with and without phenidone, and (2) phenidone-treated leaves with and without caterpillars.

To test the effect of pure phenidone on the oviposition preference of P. brassicae butterflies, intact plants were sprayed with either phenidone or control solution and the preference of P. brassicae for leaf material excised from these plants was tested 24 h later.

Oviposition preference of P. xylostella

Plutella xylostella prefers to lay eggs on cabbage leaves infested with conspecific larvae (Shiojiri and Takabayashi 2003) or Pieris rapae caterpillars over uninfested leaves (Poelman et al. 2008a; Shiojiri et al. 2002). We tested whether this preference could be modified by inhibiting LOX. The set-up of these experiments was the same as used by Poelman et al. (2008a). One male and one female moth were placed in a plastic cylinder (diameter 13 cm, height 22 cm) with two excised leaves that had been treated 24 h before. The females were allowed to oviposit overnight, and the number of eggs on each leaf was counted the next morning. We first tested leaves from an infested plant against leaves from an intact plant. Subsequently, we tested leaves from plants treated with phenidone and infested with 15 P. rapae caterpillars against leaves from intact plants treated with phenidone. Both infested (locally damaged leaves) and systemic leaves (leaves without damage, but from a damaged plant) from these plants were tested. As a final comparison we tested leaves from two infested plants against each other, one of which was sprayed with 0.1% Tween 20 and the other with phenidone solution.

Bioassays with C. glomerata

To determine whether the application of phenidone to infested plants changed the attractiveness of the plants for C. glomerata, we performed dual-choice windtunnel tests (Geervliet et al. 1994). In the windtunnel, a plant infested with P. brassicae and treated with the inhibitor was tested: (1) against a plant infested with P. brassicae without inhibitor, and (2) against an uninfested plant treated with the inhibitor. All combinations were tested on at least 5 different experimental days and the position of the plants in the windtunnel was switched after five wasps to avoid any possible directional bias. Brussels sprouts plants were treated the same way as for the herbivore experiments and tested 24 h after treatment, except that whole plants were used instead of freshly excised leaves. Naïve wasps were used when they were 4–7 days old. Female wasps were separated from the males on the day before the experiment. They were released individually in the windtunnel on a piece of leaf from a previously infested Brussels sprouts plant from which all caterpillars, their excreta and silk had been removed just prior to the experiment. The release point was 60 cm downwind from the two plants. The wasps were observed until they landed on one of the plants. When a wasp did not land on a plant within 10 min, this was recorded as no-choice, and the wasp was discarded from the analysis. The windtunnel conditions were set at 25–27°C, 60–80% RH and a wind speed of 20 cm s−1 (Thermisches Anemometer; Lambrecht, Göttingen, Germany).

Oxylipin analysis

For 12-oxo-phytodienoic acid (OPDA) and JA analysis leaf material was sampled from five plants of each of five treatments: leaves from undamaged plants, damaged leaves from plants with 15 P. rapae caterpillars, damaged leaves from plants with 15 P. brassicae caterpillars, damaged leaves from plants sprayed with 2 mM phenidone and infested with 15 P. rapae caterpillars, and damaged leaves from plants sprayed with 2 mM phenidone and infested with 15 P. brassicae caterpillars. Leaf samples were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen after sampling and subsequently stored at −80°C until analysis. For OPDA and JA analysis frozen plant material (ca. 500 mg fresh weight) was transferred into a 2-ml vial. After addition of a ceramic bead (6 mm diameter), tissue was homogenised with a vibrating ball mill (20 s−1, 3 min). Methanol (1 ml), internal standards (100 ng [D5]OPDA and 50 ng dihydrojasmonic acid), and 50 μl acetic acid were added and the mixture was homogenised again (30 s−1, 3 min). After centrifugation (10 min, 14,000 r.p.m.; centrifuge 5415C; Eppendorf, Hamburg), 800 μl of the supernatant was transferred to a 1.5-ml Eppendorf cup and dried in a vacuum centrifuge Christ Speed-Vac RVC 2-18 (Christ, Osterode am Harz, Germany). The residue was dissolved in 20 μl acetonitrile and transferred to a microvial. Prior to high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)−mass spectrometry (MS) analysis, 80 μl of ammonium acetate (1 mM, pH 6.6) was added. Analysis was carried out on a Waters/Micromass (Milford, Mass.) Quattro Premier Triple Quadrupol mass spectrometer coupled to an Agilent 1200 series (Agilent, Waldbronn, Germany) HPLC system, equipped with a 1200 binary pump and 1200 standard autosampler. A pre-column (Purospher Star 18e; 4 × 4 mm, 5-μm particle size; Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) and Purospher Star RP 18e column (125 × 2 mm, 5-μm particle size; Merck) were used. The injection volume was 15 μl, and the HPLC flow rate was 0.2 ml min−1 using the following gradient of ammonium acetate (1 mM, pH 6.6):acetonitrile—10 min at 95:5, 5 min at 5:95, then at a flow rate of 0.3 ml min−1 for 15 min at 95:5. Mass spectra were acquired using electrospray ionisation in negative ion mode and multiple reaction monitoring (MRM). The capillary and cone voltage were set at 3.00 kV and 40.00 V, the flow rates of cone gas and desolvation gas were 50 and 800 l/h, and the source temperature and desolvation temperature were 120 and 400°C, respectively. Data were acquired with MassLynx 4.1 software. Quantification of the compounds was performed by integration of the peak area in the MRM chromatograms. Oxylipin concentrations were calculated by reference to the integrated peak areas of the internal standards.

Volatile analysis

Volatiles were collected from plants: (1) sprayed with phenidone, (2) sprayed with phenidone and subsequently infested with 15 P. brassicae, and (3) sprayed with 0.1% Tween 20 and then infested with 15 P. brassicae. The headspace collection was performed in a climate room at 22–24°C, 50–70% RH and a light intensity of 95 ± 5 μmol m−2 s−1 PAR (QMSW-SS quantum meter; Apogee Instruments). Pressurised air was filtered over silica gel, a molecular sieve (4 Å) and activated charcoal, and passed through a 30-l clean glass jar. Clean air was passed through the jar at a flow rate of 100 ml/min overnight to remove any remaining volatile contaminants. Just before placing the plant in the jar, the pot of the plant was removed and the roots and soil were packed tightly in aluminium foil. The plant was placed in the jar, which was closed with a glass lid with a Viton O-ring in between and the lid was tightly closed with a metal clamp. The jar with the plant was purged for 1 h with an air flow through the jar of 50 ml/min. Subsequently, headspace volatiles were collected at the outlet of the jar for 4 h on a glass tube filled with 90 mg Tenax-TA 25/30 mesh at a flow rate of 40 ml/min. After collection the tube was closed and stored at room temperature until gas chromatography (GC)–MS analysis. Two plants of different treatments were sampled at the same time, and five or six replicates per treatment were sampled and analysed. Headspace samples were analysed with a Varian 3400 GC connected to a Finnigan MAT 95 MS. The collected volatiles were released from the Tenax by heating the trap in a thermodesorption cold trap unit (Chrompack) at 250°C for 10 min and flushing with helium at 14 ml/min. The released compounds were cryofocused in a cold trap [0.52 mm internal diameter (ID) deactivated fused silica] at −85°C. By ballistic heating of the cold trap to 220°C the volatiles were transferred to the analytical column (DB-5 ms, 60 m × 0.25 mm ID, 0.25 μm film thickness; J&W, Folsom, Calif). The temperature program started at 40°C (4-min hold) and rose 5°C min−1 to 280°C (4-min hold). The column effluent was ionised by electron impact ionisation at 70 eV. Mass scanning was done from 24 to 300 m/z with a scan time of 0.7 s/d and an interscan delay of 0.2 s. Compounds were identified by comparison of the mass spectra with those in the Wiley library and in the Wageningen Mass Spectral Database of Natural Products and by checking the retention index.

Statistical analysis

Data on parasitoid behaviour in response to the same plant treatments and obtained on different days were pooled after testing for differences between experimental days using a n × 2 contingency table test (SAS 9.1) and analysed with a binomial test (MS Excel). Herbivore oviposition preference was tested, depending on the distribution of the data, with a paired t-test or a Wilcoxon matched-pair signed-ranks test. OPDA and JA levels were compared with ANOVA with LSD post-hoc tests using SPSS 15.0. The volatile patterns of differently treated plants were analysed using principal component analysis (PCA) and projection to latent structures-discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) using the software program SIMCA-P 10.5 (Umetrics, Umeå, Sweden) (Eriksson et al. 2001; Wold et al. 1989). These methods aim to identify which compounds are important for the differences between the complex volatile blends resulting from the three plant treatments. PCA obtains so-called scores by projecting data observations onto model planes, which are defined by the extracted principal components. The integrated peak areas, corrected for the fresh weight of the plants, were normalised, i.e. peak areas of all analysed compounds (x variables) were log transformed (the constant 0.00001 was added to provide non-detectable components with a small non-zero value; Sjödin et al. 1989) and mean-centred, scaled to unit variance and represented as a matrix x (Eriksson et al. 2001). The objective of PLS-DA is to find a model that discriminates the x data according to the plant treatments (Eriksson et al. 2001). PLS-DA is a supervised technique, so class memberships of the observations need to be predefined. Therefore, an additional y matrix was made with G columns containing the values 1 and 0 as dummy variables for each of the plant treatments respectively. The number of significant PCs and PLS components were determined by cross-validation (Eriksson et al. 2001; Wold et al. 1989). In addition, we calculated the variable importance in the projection (VIP). Variables with VIP values larger than 1 are most influential for the model (Eriksson et al. 2001; Paolucci et al. 2004).

Results

Oviposition preference of P. brassicae

For the herbivores we first assessed oviposition preference for infested versus uninfested leaves. P. brassicae discriminated between infested and uninfested leaves, and preferred uninfested over infested leaves (Wilcoxon matched-pair signed-ranks test: Z = −3.244, n = 31, P = 0.001; Fig. 2a). When infested and uninfested plants were treated with phenidone P. brassicae did not discriminate between the treatments, although there still was a tendency towards preference for uninfested plants (Wilcoxon matched pair signed ranks test: Z = −1.894, n = 33, P = 0.058; Fig. 2b). When infested leaves that had been pre-treated with phenidone or control solution were compared, the butterflies did not prefer one treatment over the other (Wilcoxon matched pair signed ranks test: Z = −0.573, n = 36, P = 0.573; Fig. 2c). Phenidone treatment of intact plants did not affect P. brassicae oviposition behaviour: the butterflies did not discriminate between intact plants treated with either phenidone or control solution (Wilcoxon matched pair signed ranks test: Z = −0.211, n = 22, P = 0.842).

Oviposition preference of Pieris brassicae on a P. brassicae-infested versus uninfested (control) leaves, b phenidone-treated leaves with or without P. brassicae, c P. brassicae-infested leaves with or without phenidone. The thick line indicates the median, the box represents the interquartile range from first to third quartile. **P < 0.01. n.s. Not significant (Wilcoxon matched pair signed rank test)

Oviposition preference of P. rapae

Pieris rapae did not discriminate between infested and uninfested plants, for the experiments with 15 caterpillars per plant and 24 h feeding, although a tendency towards uninfested leaves was observed (paired t-test: t = 1.797, df = 42, P = 0.079). As expected, phenidone treatment did not affect the oviposition preference of P. rapae (Wilcoxon matched pair signed ranks test: Z = −1,656, n = 33, P = 0.099). When the amount of damage was increased by a threefold increase in caterpillar density, the butterflies did discriminate and preferred the uninfested leaves over infested leaves (Wilcoxon matched pair signed ranks test: Z = −3.531, n = 24, P < 0.001).

Oviposition preference of P. xylostella

In contrast to the Pieris butterflies, Plutella xylostella moths prefer leaves infested with Pieris rapae over uninfested leaves (Wilcoxon matched pair signed ranks test: Z = −4.541, n = 44, P < 0.001; Fig. 3a). However, when phenidone was sprayed on the plants before infestation, this treatment eliminated the preference for the infested plants (Wilcoxon matched pair signed ranks test: Z = −1.542, n = 46, P = 0.123; Fig. 3b), and did discriminate between infested plants sprayed with phenidone or Tween 20 solution, P. xylostella preferring the ones sprayed with Tween 20 (Wilcoxon matched pair signed ranks test: Z = −2.892, n = 40, P = 0.004; Fig. 3c).

Oviposition preference of Plutella xylostella on a Pieris rapae-infested versus uninfested (control) leaves, b phenidone-treated leaves with or without Pieris rapae, c Pieris rapae-infested leaves with or without phenidone. The thick line indicates the median, the box represents the interquartile range from first to third quartile. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 (Wilcoxon matched pair signed rank test)

Plutella xylostella did not discriminate between the systemic leaves (undamaged leaves from infested plants) from infested and uninfested plants, although they tended to prefer the leaves from infested plants (Wilcoxon matched pair signed ranks test: Z = −1.635, n = 41, P = 0.102). Not surprisingly, the moths did not discriminate between leaves from uninfested and infested plants either when both were treated with phenidone, but the tendency we observed in the previous comparison disappeared (Wilcoxon matched pair signed ranks test: Z = −0.110, n = 44, P = 0.912).

The moths also deposited many eggs on the cage walls. The distribution of eggs that were deposited on leaves or on the cage differed between treatments (contingency table test: χ 2 = 130.3, df = 4, P < 0.001). The percentages seem to depend on the attractiveness of the leaves offered. When the leaves from the most attractive plants in our tests (locally damaged plants without phenidone treatment) were offered as one of the two alternatives, the moths deposited on average 36 and 46% of their eggs on the cage, while for the other tests the percentages varied from 52 to 59%.

Bioassays with C. glomerata parasitoids

P. brassicae-infested plants treated with phenidone were less attractive to C. glomerata than infested plants treated with control solution (binomial test, n = 42, P = 0.008; Fig. 4). However, infested plants treated with phenidone were still more attractive than intact plants sprayed with phenidone (binomial test, n = 39, P < 0.001; Fig. 4).

Attraction of Cotesia glomerata to plants sprayed with phenidone (phen) or sprayed with a control solution, with or without infestation with Pieris brassicae (PB). Numbers to the left of the bars indicate the total number of parasitoids tested, numbers in parentheses indicate the number of parasitoids that landed on a plant. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 (binomial test)

Oxylipin analysis

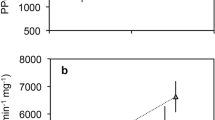

To test whether phenidone treatment of Brussels sprouts plants affects the accumulation of octadecanoid-pathway intermediates downstream from LOX, we analysed OPDA and JA levels. The results show an increase in OPDA and JA levels after P. brassicae feeding (ANOVA LSD post-hoc tests: OPDA, P = 0.001; JA, P < 0.001). Application of phenidone before infestation resulted in lower concentrations of OPDA and JA compared to the infested plant without phenidone (ANOVA LSD post-hoc tests: OPDA, P < 0.001; JA, P < 0.001; Fig. 5).

Effect of phen treatment and caterpillar infestation on a 12-oxo-phytodienoic acid (OPDA), and b jasmonic acid levels in Pieris rapae-infested (PR), PB-infested, phen-treated P. rapae-infested (PR + phen) and phen-treated P. brassicae-infested (PB + phen) Brussels sprouts plants. Different letters indicate significant differences between treatments. For other abbreviations, see Fig. 4

For P. rapae feeding the effect was similar for JA levels and somewhat less strong for OPDA. OPDA and JA levels increased upon caterpillar feeding (ANOVA LSD post-hoc tests: OPDA, P = 0.017; JA, P < 0.001) and were lower after pre-treatment with phenidone, though not significantly for OPDA (ANOVA LSD post-hoc tests: OPDA, P = 0.112; JA, P = 0.001; Fig. 5).

Volatile analysis

In the headspace of phenidone-treated intact plants, P. brassicae-infested plants, and phenidone-treated P. brassicae-infested Brussels sprouts plants, we detected 18 compounds (alcohols, esters, aldehydes, and terpenoids; Table 1). Major compounds in all volatile blends were the monoterpenes sabinene, limonene, and 1,8-cineole, and the green leaf volatile (Z)-3-hexen-1-yl acetate. Plants with feeding damage emitted many compounds in larger amounts than intact plants. Several, though not all, green leaf volatiles and terpenes were emitted in slightly lower amounts after phenidone treatment. The PCA extracted one significant principal component that explained 44.7% of the variation in the data (Fig. 6a). Although all three treatments showed considerable variation, they could be significantly separated by PLS-DA that takes the total blend into account (1 PLS-component, R 2 X = 0.418, R 2 Y = 0.333, Q 2 = 0.164). PLS-DA mostly separated the infested plants from phenidone-treated intact plants, while the phenidone-treated infested plants differ slightly from the Tween-treated infested plants (Fig. 6b). Compounds that were most influential for the separation of the groups (based on VIP values) were (Z)-3-hexen-1-yl acetate (VIP = 1.49), (Z)-3-hexen-1-ol (VIP = 1.46) and (E)-4,8-dimethyl-1,3,7-nonatriene [(E)-DMNT; VIP = 1.42; Fig. 6c].

Multivariate data analysis of the volatile pattern of plants infested with PB, phen-treated PB-infested plants (PHEN + PB), and phen-treated intact plants (PHEN). Percentage variation explained in parentheses. The ellipse defines the Hotelling’s T 2 confidence region (95%). a Score plot of principal component analysis (PCA), and b score plot of projection to latent structures-discriminant analysis (PLS-DA), and c loading plot of PLS-DA as based on the relative amounts of 20 volatile compounds from the differently treated Brussels sprouts plants. Compound identification numbers correspond to numbers in Table 1. For other abbreviations, see Fig. 4

Discussion

We demonstrate that the inhibition of the first enzymatic step in the octadecanoid pathway influences the responses of three herbivores and a parasitoid to infested Brassica plants. To our knowledge this is the first study that uses an inhibitor of the octadecanoid pathway, such as phenidone, to study not only plant responses, but to investigate also the effect of LOX inhibition on the behavioural responses to the plants by insects at two trophic levels. Treatment with phenidone before infestation reduces LOX-dependent plant responses that subsequently influence the behavioural responses of herbivorous and carnivorous insects, confirming the three hypotheses we tested. This approach provides insight into the sensitivity of insects to plant metabolomic changes resulting from induction of the octadecanoid pathway. Recently, two inhibitors (glyphosate and fosmidomycin) of other pathways (the shikimic acid and the methylerythritol 4-phosphate pathways, respectively) were shown to be suitable tools with which to study induced indirect plant defences (Bruinsma and Dicke 2008; D’Alessandro et al. 2006; D’Alessandro and Turlings 2006; Mumm et al. 2008).

Phenidone treatment of Brussels sprouts plants resulted in a reduced attractiveness of infested plants to C. glomerata. Two other inhibitors of the same pathway, diethyldithiocarbamic acid and propyl gallate, had similar negative effects on C. glomerata attraction (Bruinsma 2008). The herbivores P. rapae and P. brassicae were less sensitive to changes in plant metabolic profiles induced by caterpillar feeding and LOX inhibition respectively than their natural enemy C. glomerata. We found that P. rapae did not discriminate between undamaged plants and plants with feeding damage caused by 15 caterpillars for 24 h. Only high densities of P. rapae caterpillars (45 per plant) that are much higher than densities occurring in the field (Poelman et al. 2008a) change the oviposition preference of the butterflies. Previous studies have obtained diverse results with P. rapae oviposition. Poelman et al. (2008a) found no preferences of P. rapae for either infested or uninfested leaves of two cabbage cultivars when infested with ten P. rapae for 1 week. In contrast, Sato et al. (1999) observed a preference for Rorippa indica plants infested with 100 P. rapae larvae for 24 h in a field experiment; however, this experiment tested only one plant per treatment and the caterpillar density was unrealistically high. Bruinsma et al. (2007) compared the oviposition preference of P. rapae on JA-induced and non-induced leaves and found that the butterflies preferred non-induced leaves, at doses of 0.1 and 1 mM JA, but did not discriminate at lower doses, whereas the parasitoid C. glomerata was attracted by plants induced with 0.01 mM (Bruinsma et al. 2009). Thus, both after induction by JA or herbivores, and inhibition of the octadecanoid pathway with phenidone, C. glomerata is more sensitive to changes in plant chemistry than P. rapae.

P. brassicae was more selective than P. rapae. Large cabbage white butterflies discriminated between uninfested plants and plants that were damaged by 15 P. brassicae caterpillars for 24 h. Treatment with phenidone of both uninfested and infested plants eliminated this preference. Since C. glomerata was less attracted to infested plants when they were treated with phenidone, lower induction levels due to phenidone treatment may reduce the risk of parasitism for P. brassicae. The fundamentally different oviposition strategies of the two Pieris species can explain the difference in selectiveness between them. P. rapae is a solitary butterfly, which means that it lays a single egg at a time and spreads its eggs over many plants. P. brassicae, on the other hand, is a gregarious butterfly and lays its eggs in clusters of about 20–100 eggs, a single cluster per plant (Davies and Gilbert 1985). Depositing more than one egg cluster on a single Brassica plant is known to lead to intraspecific competition for larval food and forces larvae to migrate and search for additional host plants in order to complete larval development. Therefore, the choice of an oviposition site is likely to have higher fitness consequences for P. brassicae than P. rapae; P. brassicae can therefore be expected to be more selective. The two caterpillar species may also differentially induce the defence responses of the plant as a result of the differences in spatial distribution of feeding damage.

To test the possible effect of phenidone itself on insect behaviour, we applied phenidone to intact leaves and assessed whether the herbivores discriminated between Tween 20- and phenidone-treated leaves. For both Pieris brassicae and Plutella xylostella, phenidone neither affected oviposition preference nor the area consumed by Pieris rapae after 24 h (Wilcoxon matched pair signed ranks test: Z = −0.507, n = 7, P = 0.612). Also total development time and pupal weight did not differ between P. rapae fed on control or phenidone-treated plants (Mann–Whitney U-test, respectively: Z = −0.256, n = 19, P = 0.798; Z = −0.024, n = 19, P = 0.990). Furthermore, oxylipin analysis confirmed the inhibition of the plants’ defence response. Therefore, we ascribe our results to inhibition of the defence response of the plant regulated by the octadecanoid pathway, rather than to a direct effect of phenidone itself.

Our results show that inhibiting LOX activity reduces the plant’s indirect defence. In the arms race between plants and herbivores, any herbivore that would be able to silence a plant’s induced defence signalling would have a higher chance of surviving and reproducing. One way of accomplishing this might be to inhibit LOX activity. No herbivore has yet been shown to repress LOX activity. However, caterpillar saliva inhibited wound-induced nicotine production in tobacco (Musser et al. 2002, 2005). Furthermore, for spider mites, intraspecific variation exists in traits regarding susceptibility to JA-dependent defences as well as repression of these defences in their host plant (Kant et al. 2008), but the mechanisms underlying this observed repression have not yet been elucidated. However, the consequences of interference with LOX activity should also be seen in the context of competition among herbivores. Interference with LOX activity may increase competition from other herbivores and therefore, the selection on herbivores to interfere with LOX activity is dependent on the balance between selection pressures from natural enemies versus competitors.

Plutella xylostella prefers to oviposit on plants infested with Pieris rapae caterpillars (Fig. 3; Poelman et al. 2008a; Shiojiri et al. 2002). Shiojiri et al. (2002) showed that this is a beneficial strategy for P. xylostella. Its parasitoid Cotesia plutellae was less efficient in host searching on plants infested with both Pieris rapae and Plutella xylostella, than on plants with only Plutella xylostella. This resulted in lower parasitism rates on plants also colonised by P. rapae. We show that this preference of Plutella xylostella for Pieris rapae-infested plants over uninfested plants is LOX dependent, since phenidone treatment of uninfested and infested plants eliminated the preference. Moreover, P. xylostella females preferred infested plants sprayed with Tween over infested plants sprayed with phenidone, indicating that the phenidone treatment can reduce the induction of oviposition cues for this species. P. xylostella did not show the same preference for the systemic leaves (undamaged leaves from infested plants) as for the locally damaged leaves. Possibly the induction of systemic leaves is less strong or requires more than 24 h induction. For example, BoLOX (a LOX gene that is involved in the defence response of Brussels sprouts plants) expression after 24 h of feeding by 16 P. rapae caterpillars was upregulated in both local and systemic leaves of Brussels sprouts, but was approximately 40-fold higher in local than in systemic leaves (Zheng et al. 2007). Probably the induction level in systemic leaves is not sufficient (yet) for P. xylostella to prefer induced systemic leaves over non-induced systemic ones for oviposition.

Phenidone treatment reduced oxylipin accumulation upon Pieris feeding, as expected based on our first hypothesis (Fig. 5). Since phenidone inhibits LOX, an early step of the octadecanoid pathway, and we show that it reduces oxylipin accumulation in response to herbivory, we expected that phenidone treatment would reduce emission of green leaf volatiles and terpenoids which were shown to be induced by JA treatment of Brussels sprouts plants (Bruinsma et al. 2009). The volatile emission differed in many compounds between intact and infested plants; phenidone treatment slightly changed volatile emission of infested plants (Table 1; Fig. 6). Possibly, the large variation in volatile emission combined with low sample size obscured detection of subtle changes and changes in minor compounds that may be important for the associated insects. Yet, the three compounds that were most influential for separation of the treatment (i.e. highest VIP values), (Z)-3-hexen-1-yl acetate, (Z)-3-hexen-1-ol and (E)-DMNT, are known to elicit electrophysiological responses from the olfactory receptors of the parasitoid C. glomerata (Smid et al. 2002). Of these compounds (E)-DMNT differed most between the phenidone-treated P. brassicae-infested (mean ± SE: 0.5 ± 0.3) and Tween-treated P. brassicae-infested (1.3 ± 0.4) plants. Although the (E)-DMNT emission did differ significantly between treatments (ANOVA: F = 4.282, df = 2, P = 0.037), the difference was not significant between the phenidone-treated P. brassicae-infested and Tween-treated P. brassicae-infested plants (LSD: P = 0.083).

The results of the insect bioassays, as well as the oxylipin and volatile emission analyses, show that phenidone does not block induction completely. Lack of complete inhibition may be due to the reduction of only a fraction of the LOX molecules to the inactive form by phenidone, or to induction of plant defences by alternative routes when LOX activity is blocked. Therefore, we cannot postulate that LOX activity is crucial, but we do show that it plays an important role in plant defence against herbivorous insects in Brussels sprouts plants and affects the responses of both herbivorous and carnivorous insects.

The role of LOX in direct and indirect defences against herbivorous arthropods has now been demonstrated in several ways, through genotypic and phenotypic induction and inhibition. Genetic interference in LOX production in several plants species, such as Arabidopsis thaliana, Nicotiana attenuata and potato, resulted in reduced volatile emission, defence gene expression, attraction of parasitoids and increased plant damage in the field (e.g. Kessler et al. 2004; Royo et al. 1999; Van Poecke and Dicke 2002; Van Poecke et al. 2002). A difference between LOX inhibition with chemicals and genotypic modification is that phenidone blocks all LOXs, whereas genetic modification blocks the expression of one specific LOX gene. Combining different approaches, phenotypic manipulation (elicitors and inhibitors of different pathways) and genotypic differences (using mutants and genetically modified plants), and studying plant genomics, metabolomics as well as insect behaviour and interactions, will increase our understanding of the infochemical network that mediates interactions between plants, herbivores and their natural enemies. This will be instrumental in making progress in understanding how individual plant-insect interactions contribute to community dynamics.

References

Arimura G-I, Kost C, Boland W (2005) Herbivore-induced, indirect plant defences. Biochim Biophys Acta 1734:91–111

Bell E, Creelman RA, Mullet JE (1995) A choloroplast lipoxygenase is required for wound-induced jasmonic acid accumulation in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 92:8675–8679

Bruinsma M (2008) Infochemical use in Brassica-insect interactions: a phenotypic manipulation approach to induced plant defences. PhD, Wageningen University, Wageningen, The Netherlands

Bruinsma M, Dicke M (2008) Herbivore-induced indirect defence: from induction mechanisms to community ecology. In: Schaller A (ed) Induced plant resistance to herbivory. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, New York, pp 31–60

Bruinsma M, Van Dam NM, Van Loon JJA, Dicke M (2007) Jasmonic acid-induced changes in Brassica oleracea affect oviposition preference of two specialist herbivores. J Chem Ecol 33:655–668

Bruinsma M, Posthumus MA, Mumm R, Van Loon JJA, Dicke M (2009) Jasmonic acid-induced volatiles in Brassica oleracea attract parasitoids: effects of time and dose, and comparison with induction by herbivores. J Exp Bot 60:2575–2587

Creelman RA, Mulpuri R (2002) The oxylipin pathway in Arabidopsis. In: Somerville CR, Meyerowitz EM (eds) The Arabidopsis book. American Society of Plant Biologists, Rockville

Cucurou C, Battioni JP, Thang DC, Nam NH, Mansuy D (1991) Mechanisms of inactivation of lipoxygenases by phenidone and BW755C. Biochemistry 30:8964–8970

D’Alessandro M, Turlings TCJ (2006) Advances and challenges in the identification of volatiles that mediate interactions among plants and arthropods. Analyst 131:24–32

D’Alessandro M, Held M, Triponez Y, Turlings TCJ (2006) The role of indole and other shikimic acid derived maize volatiles in the attraction of two parasitic wasps. J Chem Ecol 32:2733–2748

D’Auria JC, Pichersky E, Schaub A, Hansel A, Gershenzon J (2007) Characterization of a BAHD acyltransferase responsible for producing the green leaf volatile (Z)-3-hexen-1-yl acetate in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J 49:194–207

Davies CR, Gilbert N (1985) A comparative study of the egg-laying behaviour and larval development of Pieris rapae L. and Pieris brassicae L. on the same host plants. Oecologia 67:278–281

De Vos M et al (2005) Signal signature and transcriptome changes of Arabidopsis during pathogen and insect attack. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 18:923–937

Dicke M (2000) Chemical ecology of host-plant selection by herbivorous arthropods: a multitrophic perspective. Biochem Syst Ecol 28:601–617

Dicke M, Van Poecke RMP (2002) Signaling in plant-insect interactions: signal transduction in direct and indirect plant defence. In: Scheel D, Wasternack C (eds) Plant signal transduction, vol 38. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 289–316

Dicke M, Vet LEM (1999) Plant-carnivore interactions: evolutionary and ecological consequences for plant, herbivore and carnivore. In: Olff H, Brown VK, Drent RH (eds) Herbivores: between plants and predators. Blackwell Science, Oxford, pp 483–520

Engelberth J, Koch T, Schuler G, Bachmann N, Rechtenbach J, Boland W (2001) Ion channel-forming alamethicin is a potent elicitor of volatile biosynthesis and tendril coiling. Cross talk between jasmonate and salicylate signaling in lima bean. Plant Physiol 125:369–377

Eriksson L, Johansson E, Kettaneh-Wold N, Wold S (2001) Multi- and megavariate data analysis: principles and applications. Umetrics Academy, Umeå

Feussner I, Wasternack C (2002) The lipoxygenase pathway. Annu Rev Plant Biol 53:275–297

Geervliet JBF, Vet LEM, Dicke M (1994) Volatiles from damaged plants as major cues in long-range host-searching by the specialist parasitoid Cotesia rubecula. Entomol Exp Appl 73:289–297

Halitschke R, Baldwin IT (2003) Antisense LOX expression increases herbivore performance by decreasing defense responses and inhibiting growth-related transcriptional reorganization in Nicotiana attenuata. Plant J 36:794–807

Heil M et al (2004) Evolutionary change from induced to constitutive expression of an indirect plant resistance. Nature 430:205–208

Heitz T, Bergey DR, Ryan CA (1997) A gene encoding a chloroplast-targeted lipoxygenase in tomato leaves is transiently induced by wounding, systemin, and methyl jasmonate. Plant Physiol 114:1085–1093

Hlasta DJ et al (1991) 5-Lipoxygenase inhibitors—the synthesis and structure–activity-relationships of a series of 1-phenyl-3-pyrazolidinones. J Med Chem 34:1560–1570

Kant MR, Sabelis MW, Haring MA, Schuurink RC (2008) Intraspecific variation in a generalist herbivore accounts for differential induction and impact of host plant defences. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci 275:443–452

Kessler A, Baldwin IT (2002) Plant responses to insect herbivory: the emerging molecular analysis. Annu Rev Plant Biol 53:299–328

Kessler A, Baldwin IT (2004) Herbivore-induced plant vaccination. Part I. The orchestration of plant defenses in nature and their fitness consequences in the wild tobacco Nicotiana attenuata. Plant J 38:639–649

Kessler A, Halitschke R, Baldwin IT (2004) Silencing the jasmonate cascade: induced plant defenses and insect populations. Science 305:665–668

Koch T, Krumm T, Jung V, Engelberth J, Boland W (1999) Differential induction of plant volatile biosynthesis in the Lima bean by early and late intermediates of the octadecanoid-signaling pathway. Plant Physiol 121:153–162

Li ZY et al (2008) Phenidone protects the nigral dopaminergic neurons from LPS-induced neurotoxicity. Neurosci Lett 445:1–6

Mumm R, Posthumus MA, Dicke M (2008) Significance of terpenoids in induced indirect plant defence against herbivorous arthropods. Plant Cell Environ 31:575–585

Musser RO et al (2002) Caterpillar saliva beats plant defences. Nature 416:599–600

Musser RO, Cipollini DF, Hum-Musser SM, Williams SA, Brown JK, Felton GW (2005) Evidence that the caterpillar salivary enzyme glucose oxidase provides herbivore offense in solanaceous plants. Arch Insect Biochem Physiol 58:128–137

Paolucci U, Vigneau-Callahan KE, Shi HL, Matson WR, Kristal BS (2004) Development of biomarkers based on diet-dependent metabolic serotypes: characteristics of component-based models of metabolic serotypes. Omics J Integr Biol 8:221–238

Piel J, Atzorn R, Gabler R, Kuhnemann F, Boland W (1997) Cellulysin from the plant parasitic fungus Trichoderma viride elicits volatile biosynthesis in higher plants via the octadecanoid signalling cascade. FEBS Lett 416:143–148

Poelman EH, Broekgaarden C, Van Loon JJA, Dicke M (2008a) Early season herbivore differentially affects plant defence responses to subsequently colonizing herbivores and their abundance in the field. Mol Ecol 17:3352–3365

Poelman EH, van Loon JJA, Dicke M (2008b) Consequences of variation in plant defense for biodiversity at higher trophic levels. Trends Plant Sci 13:534–541

Royo J et al (1999) Antisense-mediated depletion of a potato lipoxygenase reduces wound induction of proteinase inhibitors and increases weight gain of insect pests. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96:1146–1151

Sato Y, Yano S, Takabayashi J, Ohsaki N (1999) Pieris rapae (Lepidoptera : Pieridae) females avoid oviposition on Rorippa indica plants infested by conspecific larvae. Appl Entomol Zool 34:333–337

Schoonhoven LM, Van Loon JJA, Dicke M (2005) Insect-plant biology, 2nd edn. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Shiojiri K, Takabayashi J (2003) Effects of specialist parasitoids on oviposition preference of phytophagous insects: encounter-dilution effects in a tritrophic interaction. Ecol Entomol 28:573–578

Shiojiri K, Takabayashi J, Yano S, Takafuji A (2002) Oviposition preferences of herbivores are affected by tritrophic interaction webs. Ecol Lett 5:186–192

Sjödin K, Schroeder LM, Eidmann HH, Norin T, Wold S (1989) Attack rates of scolytids and composition of volatile wood constituents in healthly and mechanically weakend pine trees. Scand J For Res 4:379–391

Smid HM, Van Loon JJA, Posthumus MA, Vet LEM (2002) GC-EAG-analysis of volatiles from Brussels sprouts plants damaged by two species of Pieris caterpillars: olfactory receptive range of a specialist and a generalist parasitoid wasp species. Chemoecology 12:169–176

Turlings TCJ, Tumlinson JH, Lewis WJ (1990) Exploitation of herbivore-induced plant odors by host-seeking parasitic wasps. Science 250:1251–1253

Van Poecke RMP (2007) Arabidopsis-insect interactions. In: Somerville CR, Meyerowitz EM (eds) The Arabidopsis book. American Society of Plant Biologists, Rockville

Van Poecke RMP, Dicke M (2002) Induced parasitoid attraction by Arabidopsis thaliana: involvement of the octadecanoid and the salicylic acid pathway. J Exp Bot 53:1793–1799

Van Poecke RMP, Posthumus MA, Dicke M (2002) Signal transduction in Arabidopsis: molecular genetic and chemical analysis of different genotypes. In: Van Poecke RMP (ed) Indirect defence of Arabidopsis against herbivorous insects: combining parasitoid behaviour and chemical analysis with a molecular genetic approach. Thesis, Wageningen, pp 81–101

Van Zandt PA, Agrawal AA (2004) Community-wide impacts of herbivore-induced plant responses in milkweed (Asclepias syriaca). Ecology 85:2616–2629

Wold S et al (1989) Multivariate data analysis: converting chemical data tables to plots. Intell Instrum Comput 19:7–216

Zheng S-J, Van Dijk J, Bruinsma M, Dicke M (2007) Sensitivity and speed of induced defense of cabbage (Brassica oleracea L.): dynamics of BoLOX expression patterns during insect and pathogen attack. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 20:1332–1345

Acknowledgments

We thank Leo Koopman, André Gidding and Frans van Aggelen for the supply of insects, Unifarm for the supply of plants, Ferran Bustos Salvador and Hans van den Biggelaar for their help with the Plutella experiments, Gabriele Gresser for her contribution to the oxylipin analysis, and Roland Mumm for advice on the data analysis of the volatile patterns. This work was financially supported by a VICI grant from the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research, NWO (865.03.002). We declare that all experiments presented in this manuscript comply with the current laws of the countries in which they were performed (The Netherlands and Germany).

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by Richard Karban.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Bruinsma, M., van Broekhoven, S., Poelman, E.H. et al. Inhibition of lipoxygenase affects induction of both direct and indirect plant defences against herbivorous insects. Oecologia 162, 393–404 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-009-1459-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-009-1459-x