Abstract

A key requirement for the successful implementation of the Landing Obligation is the need to monitor and regulate unwanted catches at sea. This issue is particularly challenging because of the large number of vessels and trips that need to be monitored and the remoteness of vessels at sea. Several options exist in theory, ranging from patrol vessels to onboard observers and self-sampling. Increasingly though, technology is developing to provide remote Electronic Monitoring (EM) with cameras at lower costs. This chapter first provides an overall synthesis of the pro’s and con’s of several monitoring tools and technologies. Four EM technologies already trialled in EU fisheries are then summarised. We conclude that it is now possible to conduct reliable and cost-effective monitoring of unwanted catches at sea, especially if various options are used in combination. However, effective monitoring is a necessary condition for the successful implementation of the Landing Obligation but insufficient unless it is implemented with a high level of coverage and with the support of the fishing industry.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

Discarding in fisheries is driven by a combination of economic and regulatory factors. Fishers may choose to discard fish which are small, damaged, or of low-value to free up space on their vessels for more valuable catches, or they may lack sufficient quota to legally land a species, resulting in them being obliged or incentivised to discard that part of their catch. Global studies have systematically estimated high levels of discard rates in many European fisheries in the North East Atlantic (Kelleher 2005; Zeller et al. 2018). Catchpole et al. (2017) estimated that prior to the establishment of the Landing Obligation, discards of demersal species regulated by quota represented on average 30% of the catch. Of these, small fish (under Minimum Conservation Reference Size) represented only 30–40% of the total discards, highlighting that most discards in Atlantic EU countries are due to quota restrictions and/or are market driven. The scale of the issue demonstrates that there are strong incentives to discard when the practice is unregulated. Thus, a key challenge of the Landing Obligation is adequate enforcement, with two purposes: i) to force selectivity improvements and reduce incentives to discard and ii) to provide reliable catch statistics, since bias in catch estimation has a direct and negative impact on the precision of stock assessments.

A number of approaches are in theory available to conduct MCS (Monitoring, Control and Surveillance) activities. “Monitoring “is defined as the collection of data on catch and fishing effort;” Control “as the regulations and legislation required to stop illegal discarding, and “Surveillance” is defined as the tools available to measure compliance with the Landing Obligation.

This chapter aims first at reviewing the currently available and emerging options for the MCS of discarding of unwanted catches. Many approaches have been applied in a variety of fisheries for decades and their pro’s and con’s are therefore well-established. Then, this chapter focuses on a more in-depth review and analysis of the recent experiences gained in Europe with Remote Electronic Monitoring (REM –or simply EM) by summarising the main technologies currently available in European fisheries, and their use so far.

2 Available and Emerging Measures for MCS

A literature review for the various MCS options was conducted and synthesised. The options are briefly presented sequentially, and their advantages and disadvantages are summarised in Table 18.1.

2.1 Aerial and Patrol Vessel Surveillance

The use of aircraft (airplanes, helicopters) and patrol vessels for the MCS of fishing activities is a conventional method used in a variety of modern fisheries (Mangi et al. 2015). There are a number of advantages and disadvantages associated with both aerial and patrol vessel surveillance (European Union 2011; Course 2015) . With regards to advantages, both act as a high visibility deterrent for fishing vessels, and it has been observed that discarding is unlikely to occur whilst aerial or vessel patrols are in the vicinity. Also, both are able to observe non-national vessels which may partake in illegal fishing, providing fishers with a “level-playing field “where all boats in the area are under equivalent surveillance. Finally, they are able to monitor fishing on vessels of all sizes, including small ones.

There are however a number of disadvantages. Both aerial and patrol vessels have limitations in the monitoring of discarding, as they only supply data regarding fishing effort and not catch quantities or composition. Even then, data is limited, as coverage is extremely low. In the UK for example, aerial surveillance only monitored 0.026% of fishing effort (hours at sea) in 2013, and patrol vessel surveillance 0.05% of fishing effort (Course 2015). With such a small level of surveillance, this tool may only provide a short-term deterrent as there is no assurance that fishers will continue to comply when vehicles leave the area. A further disadvantage is the high cost associated with aerial and patrol vessel surveillance. It was estimated in 2011 that the Norwegian government spent £86 m a year for the coastguard, which used 70% of their time to enforce its discard ban (European Union 2011) . Despite this, patrol vessel surveillance remains at the heart of the control activity deployed by EU Member States together with the European Fisheries Control Agency EFCA (Nuevo et al., this volume).

Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs, or drones) and unmanned surface vessels (USV) offer a cheaper mechanism for the surveillance of unwanted catches (Miller et al. 2013; Selbe 2014; Linchant et al. 2015). High-resolution optical cameras mounted on drones or USVs enable their operators to visually observe discarding in a range of weather conditions and during both day and night. Drones can also be used to monitor the bycatch of marine mammals. However, lacking a crew, USV’s are unable to intervene if an illegal activity is observed, and can be vulnerable to hostile acts from vessels engaged in illegal activities. Furthermore, the legal position of USVs is unclear in some situations and operating a USV inside the national waters of another country could be considered a hostile act (Selbe 2014).

2.2 Vessel Transmitted Information and Vessel Detection Systems

Vessel-transmitted information is a general term for all routinely collected control data transmitted from fishing vessels to relevant on-shore authorities. The most common information covered is positional, such as Vessel Monitoring System (VMS) data - a well-established tool used in fisheries management and surveillance globally. The installation of VMS transmitters on fishing vessels is mandatory for all EU vessels above 12 m in length.

VMS data is transmitted via satellite from fishing vessels on a variable timescale, often between 30 min and 2 h intervals. In addition to location, transmissions can provide information regarding a vessel‘s speed and direction. The data transmitted through VMS can be used to infer spatial distribution of fishing effort (Needle and Catarino 2011) which then has a wide range of scientific and monitoring applications (e.g., Murawski et al. 2005; Lee et al. 2010; Aanes et al. 2011, ICES 2017).

VMS systems are present and active on fishing vessels at all times, and therefore represent a long-term deterrent to illegal fishing in closed areas (Davis 2000; Needle and Catarino 2011; Skaar et al. 2011). Additionally, VMS offers a less expensive alternative to surveillance vehicles, and the data provided are entirely autonomous from the skipper. But their utility remains nevertheless limited, since VMS does not provide information on catch. This is further reduced by infrequent transmissions, resulting in low resolution of spatial data and the potential for illegal fishing activity to take place between transmissions.

Electronic catch reporting (e-log) is another widely applied MCS tool. Catches are entered by the vessel’s skipper into an electronic logbook system and transmitted to control authorities on a daily or haul-by-haul basis. This means that accurate catch records can be made available to inspectors in advance of boarding and preliminary figures for catches aboard a vessel in advance of dockside inspection, reducing the potential for misreporting and high-grading. However, a key issue with e-log is the lack of incentive to accurately report discards at sea, if not constrained by other regulatory frameworks auditing them (Ulrich et al. 2015), so discard reporting must be framed in a dedicated self-sampling program (see Sect. 18.2.4 below).

The coupling of both sources of information (VMS and e-log) represents a powerful tool for the fine-scale mapping of catch patterns (e.g. Bastardie et al. 2010; Gerritsen et al. 2012; Hintzen et al. 2012; Ducharme-Barth et al. 2018; Russo et al. 2018), which can thus inform discard reduction strategies in real time. Such an approach was taken by the Scottish “real-time closures” scheme as one part of the North Sea cod recovery program, which aimed to establish a rolling set of closures and effort-penalised areas. These areas were based on the CPUE of cod, calculated from VMS-based effort and electronic catch reports made by fishers, at a spatial resolution of one quarter of an ICES statistical rectangle (Bailey et al. 2010). Non-compliance with this scheme, monitored through VMS, resulted in vessels losing the additional time at sea which they were granted for participating.

A further tool available to monitor fishing vessels is satellite surveillance technology and Vessel Detection Systems (VDS). VDS can detect vessels at sea under most weather conditions and information can be cross-checked with VMS positions to identify the vessel. Fishers are unable to detect VDS whilst at sea, and therefore VDS systems may be a long-term deterrent to fishing in prohibited areas. However, the coverage remains limited because of the high costs associated with satellite imaging. An alternative approach to spatial monitoring is the use of automatic identification system (AIS) data. AIS is an automatic tracking system installed on ships and initially developed by vessel traffic services as a collision avoidance mechanism. Vessels fitted with AIS transceivers can be tracked by base stations located along coast lines and when out of range of terrestrial networks, through a number of satellites fitted with specialised AIS receivers.

An advantage of AIS over other VMS-approaches is that since its primary purpose is navigational, the data are freely available and emitted more frequently. AIS data have been used by academics and NGOs (e.g. Natale et al. 2015; Russo et al. 2016; ICES 2017) to study fishing patterns and demersal impacts. A hindrance in its use as a discard monitoring tool is that it does not monitor catches nor provide information on gear used. Furthermore, as the system is based upon VHF radio transmissions, the range from land over which it is reliable is variable, but often around 60 km. Finally, a disadvantage is that much of the fleet is not required to carry AIS. The International Maritime Organization’s International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea requires AIS to be fitted aboard vessels larger than 300 GT, and all passenger ships regardless of size. Therefore the usefulness of AIS in monitoring compliance with discard regulations is overall limited.

2.3 Onboard Observers

Onboard observers are a key part of both MCS and scientific data collection in fisheries globally (Kennelly and Borges 2018; Fernandes et al. 2011). Observers usually remain on a vessel throughout a trip and collect data on the quantities and composition of the catch, discard rates, biological characteristics (such as length, weight and age), fishing effort (Cotter and Pilling 2007; Mangi et al. 2015), and collect tissue samples and otoliths. Observers may also have a role in enforcing fishery regulations, by increasing compliance trough changing fisher’s behaviour or by documenting any illegal fishing activities taking place during the trip (Porter 2010). But in many jurisdictions, there is a clear regulatory distinction between scientific and control functions of observers.

Observers are arguably the most valuable source of data on catch and fishing effort, and data collected by observers programs have been used extensively in fisheries management (Benoit and Allard 2009). For example, near real-time management of discarding in Alaskan fisheries is achieved using the high-quality data recorded through a full coverage observers program (Kennelly 2016). Data may also be used to monitor the bycatch of vulnerable species (Piovano and Gilman 2017). Observers can also act as a bridge between science and industry (Mangi et al. 2015), which may contribute to increased compliance with legislation such as the Landing Obligation.

Onboard observers are thus an appropriate tool for the MCS of unwanted catches and the precision of observers data is generally high. However, the main issue is the often-limited coverage of observers programs due to high costs, lack of human resources and/or safety concerns, among others. Observer programs in Scotland and England for example only covered 0.3% of the fishing fleet in 2013 (Course 2015) and observer programs in Fiji only covered 16.7% of the long-line fishery (Piovano and Gilman 2017). A low coverage may not guarantee that the data collected is representative of the whole fleet. Additionally, there is evidence that fishers may exhibit a change in behaviour when observers are onboard (known as observer’s effect), leading to bias in the data collected (Liggins et al. 1997), and observed in Europe particularly since the LO came into force (Borges and Dalskov 2018). This can also happen if the data collected by onboard observers is to be used to inform future quota decisions and management. This was documented in the North Pacific Groundfish Observer Program, where fishers avoided areas of high bycatch because data collected by observers are used to extrapolate bycatch rates for quota deduction (Faunce and Barbeaux 2011).

Additionally, with observer coverage on only a sample of the fleet, non-random deployment effects may occur (Benoit and Allard 2009; Faunce and Barbeaux 2011). In Europe, efforts are made to avoid this by designing statistically sound sampling programs in the frame of the EU Data Collection Framework (European Union 2016; Rodríguez-Gutierrez et al. 2018) .

Whatever the purpose of the observers program, when working under discard reduction measures such as the Landing Obligation, observers should be strongly protected (by having safety training and procedures in case of emergency, adequate regulatory framework, successful prosecutions when interfered, among others), as they inevitably are perceived by fishers to have an enforcement role. In Europe, with the majority of the industry having negative views towards the Landing Obligation (Mangi et al. 2015; Plet-Hansen et al. 2018), there is potential for increased hostility from fishers towards onboard observers (Porter 2010). Ultimately, if the programme coverage is low, an effort should be made to increase the sampling levels. This is not only to guarantee observers safety but to avoid bias in the data collected (Kennelly and Borges 2018).

2.4 Self-Sampling

Another solution for the MCS of unwanted catches is the use of data collected or sampled by fishers. Information collected and reported are typically related to catch (total catch and catch composition) and fishing activity (location, duration of fishing activity). Fishers may also be required to take samples, such as tissue samples and otoliths, from the catch (Pennington and Helle 2011). Data may be recorded electronically or on paper and entered into a database upon return. This information can then be processed and incorporated in stock assessments and management purposes, therefore having a role in the control of fishing activity.

Self-sampling and recording by fishers is a technique used for data collection in a variety of fisheries, and may be mandatory through legislation. In principle, EU fishers have been legally required to document discards over 50 kg since 2011, although this measure has largely not been enforced (Ulrich et al. 2015). However, the self-reporting may also be voluntary. In the Norwegian purse-seine fishery, fishers are paid to measure a sub-sample of fish from selected catches as well as collect otolith, stomach and genetic samples (Pennington and Helle 2011).

There are a number of advantages and disadvantages associated with the use of self-sampling for the MCS of unwanted catches (Lordan et al. 2011; Kraan et al. 2013). The major attraction of self-sampling for data collection is that a significant increase in sampling coverage can be achieved at little cost. Many studies have found that fishers welcome being involved with the data collection; although enthusiasm may drop over time (Mangi et al. 2014, 2015). Such engagement with the management process is a key ingredient to success in many fisheries. Additionally, fishers do not need to provide extra accommodation or room on vessels for outside observers. If correctly executed and following unbiased sampling protocols, data collected through self-reporting can be of high quality and used in stock assessment, as in the New Zealand rock lobster potting fishery (Starr 2000).

Though self-sampling is an effective, low-cost method, there are many disadvantages associated with the sampling technique. With negative attitudes towards the Landing Obligation widespread in the fishing industry, non-compliant behaviour may be common and self-reported data may be biased by non-random sampling or even fabricated (Ticheler et al. 1998; Graham et al. 2011; Mangi et al. 2016; Gray and Kennelly 2017). Data precision may also be below the level required for stock assessments. Data collected by fishers must therefore be quality assured and it is unlikely that self-sampling could be used as a stand-alone tool for monitoring compliance with the Landing Obligation.

2.5 Electronic Monitoring with Video

Electronic monitoring with video (EM) has been praised by many as a practical, innovative, and applicable solution for MCS in fisheries (Mangi et al. 2015; Course 2015; Mortensen et al. 2017). Through the combination of video cameras (initially analogue and closed circuit (CCTV), now mainly digital), GPS and sensor data, EM can be used to collect information regarding spatial fishing effort and catch data, which can then be used for monitoring and compliance. EM is already used in many fisheries in the world, as a full MCS program in North America and Australia, but with numerous trials also ongoing in South America and the Pacific. In EU, EM has been trialled in a number of fisheries since 2008, mainly associated with the Cod Catch Quota Management with fully documented fisheries (FDF) (Kindt-Larsen et al. 2011; Needle et al. 2015; Ulrich et al. 2015), but also to observe protected species (Kindt-Larsen et al. 2016).

EM with video meets most of the criteria necessary for the MCS of unwanted catches and has important advantages (McElderry 2006; Mangi et al. 2015; Course 2015). EM records from many sensors and at a much higher frequency than VMS or AIS (usually several times a minute). This information provides very rich granularity to distinguish specific vessel behaviours (e.g., gear setting, hauling, haul back, catch stowage, transit, etc.). EM offers thus the opportunity for 100% surveillance of fishing activities. Furthermore, EM has the ability to monitor illegal discarding, with video covering upper deck and lower deck discharge chute(s). Detection of illegal activity could potentially be used in prosecution (McElderry and Turris 2008; Diamond and Beukers-Stewart 2011). With EM systems recording vessel location and behaviour throughout a fishing trip, the technology is considered a plausible long-term deterrent to non-compliant behaviour (Course 2015).

EM is also suitable for monitoring unwanted catches, providing detailed data such as catch composition and length frequencies through video analysis (Needle et al. 2015; Sandeman et al. 2016). Such data can then be used for quota management or for the control of unwanted catches, for example, by closing fishing grounds if catches appear to be comprised of a large percentage of juveniles, vulnerable, or otherwise non-target species. Finally, while initial purchase and installation costs can be significant, running costs are low, and the amortized cost over the life of the equipment is thus very low as compared to human observers.

EM is however not without shortcomings. The main concern is the usually strong reluctance of fishers to accept onboard cameras that can be watched by the authorities. This lack of support from the industry is a major threat against the successful implementation of all MCS tools (Lordan et al. 2011; Kennelly 2016; Plet-Hansen et al. 2018). Incentives have been used to gain support by offering e.g. increased quota, days-at-sea, access to fishing grounds or more flexible gear use. In the cases where EM has been successfully implemented as full MCS programs, EM was first introduced offering incentives, and later made mandatory to all.

An older concern regarding the use of video footage was that data quality could be inconsistent. A meta-analysis by Wallace et al. (2013) found that, in almost all of the 59 EM studies reviewed, data quality was either poor or missing for a proportion of the study. However, modern technology including digital cameras has significantly improved data quality, so these issues are now less of a concern (Bergsson et al. 2017). Nevertheless, monitoring through video may remain challenging on vessels in mixed fisheries catching high volumes and with a diverse species composition (van Helmond et al. 2015). Considerations must thus be made regarding camera type and set up, and changes to conveyor belt layout may be necessary to reduce the volume of fish per video frame.

Another concern is about data quantity. If fisheries were to widely apply EM for the collection of catch data, this would represent a very large volume of data. If inspection is conducted manually by fisheries inspectors, a large onshore team of video viewers would need to be trained and employed to analyse such data. Viewing strategies and technology are therefore required to overcome this. First, viewing time can be reduced by selecting a representative sample of the fishing trips rather than all hauls. Second, video review involving machine learning and artificial intelligence to automatically analyse video footage is advancing (French et al. 2015; Bergsson et al. 2017).

In any case, even if only a portion of video recordings is reviewed, a key element of EM is that the awareness that everything is recorded and can be inspected anytime is expected to have an effective deterrent effect and increase compliance by fishers (Ulrich et al. 2015).

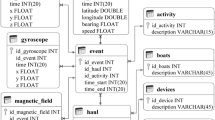

3 Overview of the EM Technology Trialled in EU

Several EM trials have been done in several EU countries since 2008, for different purposes and with different technologies. Initial trials used the EM Observe™ technology developed by Archipelago Marine Research (Canada), but new software was later developed within the EU. We briefly summarise the main features and technical characteristics of four systems: The EM Observe™ system (now operated by Marine Instruments since 2017), the Black Box developed by Anchor Lab K/S (Denmark), the Electronic Eye developed by Marine Instruments (Spain), and the iObserver system developed by CSIC (Spain) (Table 18.2).

The EM Observe™ is the first commercial EM system in the world and is used in several national monitoring programs with 100% fleet coverage of fleets comprising more than 200 vessels. It has been trialled by North Sea countries during various cod catch quota trials in the period 2008–2016 (see references in Table 18.2). Data are recorded on high capacity hard drives which are manually retrieved and replaced when the fishing vessel returns to port. The data are analysed using the EM Interpret software.

The AnchorLab Black Box system was developed to further support the EM trials in Denmark and has been used in a diversity of fisheries. Its main feature is the improvement of video storage and data transmission, where EM data are transmitted to the data receiver via GSM, Wi-Fi, 3G, 4G/LTE, LTE-A or satellite. The analyser software has a number of features facilitating length measurements including grid overlay and measuring line. A low power version to suit small-scale vessels and automated species identification for the system are under development.

The Marine Instruments’ Electronic Eye eEYE™ is in operation on a number of Spanish tuna purse seiners mainly to monitor the bycatch of endangered, threatened and protected species. It is also installed on some Scottish scallop dredgers. Data are stored in an internal hard drive and can be downloaded via USB or Wi-Fi. The cameras can also be visualised from the bridge.

The iObserver system has been developed by the scientific institute CSIC in Spain, but is not yet in operation onboard commercial vessels. It is not a full EM system as it does not observe the fishing deck, but is mainly focused on developing algorithms for robust automatic species recognition and size estimation of fish passing on the conveyor belt.

The four systems are quite different in their set up and operation and offer different capabilities. In their current state of development at the time of writing, they are not fully automated and still require human intervention for footage viewing, and their base price (system alone) is in the order of 6000–10,000 EUR per vessel. A direct comparison is however not possible as the systems have not been trialled on the same vessels and for the same purposes.

Additionally, a number of other EM systems are used throughout the world, but have not been trialled in Europe.

4 Discussion

4.1 Comparison of EM with Other MCS Options

This chapter has reviewed the pro’s and con’s of available and emerging approaches to the MCS of unwanted catches. All tools have advantages and disadvantages, but the potentials of EM technology seem nevertheless to surpass those of other more conventional tools presently used. With over 25,000 fishing days at sea monitored by EM studies, the conclusion is that such technology can be efficient and a practical method for the MCS of fishing activities (McElderry 2006; Course 2015). Compared to VMS it is obvious that EM offers much higher resolution information. VMS alone only enables the monitoring of geographical location, speed and direction. Compared to aerial and patrol vessel surveillance, the major benefit of EM with video is the potential coverage (i.e. amount of monitoring) that can be achieved. While surveillance through aerial and water-borne vehicles can only cover a small percentage of the fishing fleet and activity, EM has the potential for 100% surveillance of fishing activities, including catch monitoring, and at much lower cost.

Compared to onboard observers, while these can also offer full coverage, EM represents only a fraction of the cost (see below). Another major benefit of EM to onboard observers is its potential to offer 24/7 coverage, as it is not affected by differences in working times or by weather and is also less intrusive than accommodating an extra person onboard. On the other hand, EM cannot collect certain types of data otherwise provided by onboard observers, including tissue samples, weight measurements and otoliths. Onboard observers will therefore always be necessary if such data is required (Kennelly and Borges 2018). EM can neither provide a bridge between science and industry, improving communication and understanding.

Compared to self-sampling, a major advantage of data collected through EM is that data is anticipated to not be biased. Though research has found that information from self-sampling often reflects that from the EM videos, there is a lack of confidence in data collected when no surveillance and auditing is present (Ulrich et al. 2015). EM allows for the quality of self-reported data to be checked, and quality assured.

4.2 EM Costs

A number of studies have compared the costs of EM with observers. In the early days of development, McElderry and Turris (2008) stated that EM could be provided at a quarter of the daily cost of observers, Ames et al. (2007) a third and Kindt-Larsen et al. (2011) a tenth. Start-up and installation costs have remained high because of the limited consumer market and the specific requirements for the technology. However, operating and amortized costs are low and it takes only short time for the cumulated investment to become comparatively cheaper than observers (Needle et al. 2015). Improved technology using 3G/4G networks rather than hard disks and ensuring better connectivity between boat and shore (and reverse) has already contributed to reducing transmission costs (Mortensen et al. 2017).

A cost that has remained important in EM concerns data analysis. Video footage still needs to be manually reviewed and this may appear as a tedious and often expensive procedure. However, trials conducted over several years have contributed to the development of efficient analysis software and streamlined procedures that have significantly reduced review time. Bergsson et al. (2017) estimated that the catches of five gadoid species in a standard demersal trawl haul could be viewed and analysed in about 20 min. In the near future, it can be expected that technical advances involving computer learning and automatic image analysis will further reduce analysis costs.

Ultimately, the most important element in estimating analysis costs remains thus the number of hauls to be viewed and the amount of data to be collected. These depend on the design of the MCS program, its objectives and the required accuracy and precision of estimates. To reduce costs, EM can be used in combination with self-reporting. Self-reported catch data from fishers can be in broad agreement with EM analysis, provided that protocols are clear and that there is regular quality control and follow-up with fishers. EM can thus be used not as the main source of catch data but only to audit self-reported data, like black boxes used in trucks and airplanes. In doing so, a smaller amount of footage would be analysed, reducing costs of onshore viewers. For example, Needle et al. (2015) estimated that to obtain accurate estimates of all discarded species in a Scottish mixed demersal fishery from video footage alone, around 40% of footage must be reviewed. But other studies have found that in order to audit self-reported data, reviewing only 5–10% of hauls was sufficient (Roberts et al. 2015; Stanley et al. 2015).

4.3 Combination of Tools for Successful MCS Programs Design

Successful MCS programs have in reality involved a combination of tools. For example, in the Canadian Ground Fish Hook and Line Catch Monitoring Programme, dockside monitoring is used in conjunction with self-reported data and EM or onboard observers. This program is unique as fishers are offered a choice between EM and onboard observers, though observers are rarely used. Both EM and observers’ data are used to audit self-reported data, with full dockside monitoring providing further validation of data regarding catch (Stanley et al. 2015). This combination of tools results in the increased reliability of self-reported data, and gives the fishers some buy-in because they are collecting the data (both logbook and audit data) themselves, which gives them more ownership.

Iceland provides a different example. For a long time, compliance with the discard ban has been performed using patrol vessel surveillance combined with logbooks and catch comparisons (European Union 2011) . Fish are monitored throughout the whole supply chain. Data from the electronic logbooks, official weighings at harbour scales, purchasing receipts /receipts from fish auction, reweighing by processors, processing arrangement slips/production reports, sales- /export reports are all sent to the Directorate of Fisheries, which is then able to monitor for consistency in the mass balance (Óskarsdóttir and Gunnlaugsson 2015). Similar regulations are in place in some other countries where electronic data sharing and transparency is well advanced e.g. Faroe Islands and Norway. This type of monitoring is efficient in combination with other MCS tools and gives the authorities an indication of where they need to focus extra attention. The success of the discard ban in Iceland is also attributed to changes in social perception, with fishers themselves having the opinion that discarding is unacceptable and even reporting others if they are seen discarding (Karp et al., this volume). Nevertheless, none of the countries referred above have an independent large scale at-sea monitoring program, where discards quantities can be audited and verified. It is therefore noticeable that Iceland is currently moving towards introducing EM in its MCS programme. At the time of writing, the Directorate of Fisheries is considering a regulation which will require all commercial fishing vessels to be equipped with EM with video to remotely and electronically monitor potential discarding (Karp et al., this volume). Drones may also be introduced.

5 Conclusions

In conclusion, there are existing options to appropriately monitor and control the Landing Obligation, and the increased experience with their use together with technological developments will contribute to enhancing their capacity and reducing their costs. Nevertheless, MCS technology is only a tool and will not solve the discard issue alone. The crucial elements for the successful implementation of the Landing Obligation remain the MCS coverage level and compliance from the fishing industry. If the industry support remains low, there will always be ways to render MCS programs ineffective, especially if their coverage is low. Moving forward, this means that MCS is a necessary but insufficient tool for the successful reduction of discards, and MCS programs must thus be integrated into a broad mind shift within the fisheries and seafood sectors towards better accountancy, transparency and sustainability, and/or implemented with a high level of coverage.

References

Aanes, S., Nedreaas, K., Ulvatn, S. (2011). Estimation of total retained catch based on the frequency of fishing trips, inspections at sea, transhipment, and VMS data. ICES Journal of Marine Science, 68(8), 1598–1605.

Ames, R., Leaman, B., Ames, K., (2007). Evaluation of video technology for monitoring of multispecies longline catches. Northern American Journal of Fisheries Management, 27, 955–964.

Bailey, N., Campbell, N., Holmes, S., Needle, C., Wright, P. (2010). Real time closure of fisheries. European Parliament Directorate-General for Internal Policies. Brussels. 56 pp.

Bastardie, F., Nielsen, J.R., Ulrich, C., Egekvist, J., Degel, H. (2010). Detailed mapping of fishing effort and landings by coupling fishing logbooks with satellite-recorded vessel geo-location. Fisheries Research, 106(1), 41–53.

Benoit, H.P., & Allard, J. (2009). Can the data from at-sea observer surveys be used to make general inferences about catch composition and discards? Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, 66(12), 2025–2039.

Bergsson, H., Plet-Hansen, K.S., Jessen, L.N., Jensen, P., Bahlke, S.Ø. (2017). Final report on development and usage of REM systems along with electronic data transfer as a measure to monitor compliance with the Landing Obligation – 2016. Danish AgriFish Agency, Ministry of Food, Agriculture and Fisheries. 61 pp. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.23628.00645.

Borges, L. & Dalskov, J. (2018). Workshop 1 – European Union landing obligation. In Kennelly, S.J., & Borges, L. (Eds.). Proceedings of the 9th International Fisheries Observer and Monitoring Conference, Vigo, Spain. ISBN: 978-0-9924930-7-3, 397 pages.

Catchpole, T., Ribeiro-Santos, A., Mangi, S.C., Hedley, C., Gray, T.S. (2017). The challenges of the landing obligation in EU fisheries. Marine Policy, 82, 76–86.

Cotter, A.J.R., & Pilling, G.M. (2007). Landing, logbooks and observer surveys: Improving the protocols for sampling commercial fisheries. Fish and Fisheries, 8(2), 123–152.

Course, G. (2015). Electronic monitoring in fisheries management. WWF, UK. 38 pp.

Davis, J.M. (2000). Monitoring control surveillance and vessel monitoring system requirements to combat IUU fishing. FAO, Rome. 13 pp.

Diamond, B., & Baukers-Stewart, B. (2011). Fisheries discards in the North Sea: Waste of resources or a necessary evil? Reviews in Fisheries Science 19(3), 231–245.

Ducharme-Barth, N.D., Shertzer, K.W., Ahrens, R.N. (2018). Indices of abundance in the Gulf of Mexico reef fish complex: A comparative approach using spatial data from vessel monitoring systems. Fisheries Research, 198, 1–13.

European Union. (2011). Studies in the field of the common fisheries policy and maritime affairs. Lot4: Impact assessment studies related to the CFP. Impact assessment of discard reducing policies: Case study annex. European Commission. Brussels.

European Union. (2016). Commission Implementing Decision (EU) 2016/1251 of 12 July 2016 adopting a multiannual Union programme for the collection, management and use of data in the fisheries and aquaculture sectors for the period 2017-2019 (notified under document C(2016) 4329). C/2016/4329. Official Journal of the European Union, L207/113.

Faunce, C.H., & Barbeaux, S.J. (2011). The frequency and quantity of Alaskan groundfish catch-vessel landings made with and without an observer. ICES Journal of Marine Science, 68(8), 1757–1763.

Fernandes, P., Coull, K., Davis, C., Clark, P., Catarino, R., Bailey, N., et al. (2011). Observations of discards in the Scottish mixed demersal trawl fishery. ICES Journal of Marine Science, 68(8), 1734–1742.

French, G., Fisher, M.H., Mackiewicz, M., Needle, C. (2015). Convolutional neural networks for counting fish in fisheries surveillance video. In Amaral, T., Matthews, S., Plötz, T. et al. (Eds.). Proceedings of the machine vision of animals and their behaviour (MVAB), (pp. 7.1–7.10). BMVA Press, Swansea. ISBN 1-901725-57-CX.

Gerritsen, H., Lordan, C., Minto, C., Kraak, S. (2012). Spatial patterns in the retained catch composition of Irish demersal otter trawlers: High-resolution fisheries data as a management tool. Fisheries Research, 129–130, 127–136.

Graham, N., Grainger, R., Karp, W.A., MacLennan, D.N, MacMullen, P., Nedreaas, K. (2011). An introduction to the proceedings and a synthesis of the 2010 ICES Symposium on Fishery-Dependent Information. ICES Journal of Marine Science, 68(8), 1593–1597.

Gray, C.A., Kennelly, S.J. (2017). Evaluation of observer- and industry-based catch data in a recreational charter fishery. Fisheries Managment and Ecology, 24(2), 126−138.

Hintzen, N.T., Bastardie, F., Beare D., Piet, G.J., Ulrich, C., Deporte, N., et al. (2012). VMStools: Open-source software for the processing, analysis and visualization of fisheries logbook and VMS data. Fisheries Research, 115–116, 31–43.

ICES. (2017). Interim Report of the Working Group on Spatial Fisheries Data (WGSFD), 29 May – 2 June 2017, Hamburg, Germany. ICES CM 2017/SSGEPI:16.

Karp, W.A., & McElderry, H. (1999). Catch monitoring by fisheries observers in the United States and Canada. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Integrated Fisheries Monitoring. Rome: FAO.

Karp, W.A., Breen, M., Borges, L., Fitzpatrick, M., Kennelly, S. J., Kolding, J., et al. (this volume). Strategies used throughout the world to manage fisheries discards – Lessons for implementation of the EU Landing Obligation. In S.S. Uhlmann, C. Ulrich, S.J. Kennelly (Eds.), The European Landing Obligation – Reducing discards in complex, multi-species and multi-jurisdictional fisheries. Cham: Springer.

Kelleher, K. (2005). Discards in the world’s marine fisheries – An update (FAO Fisheries Technical Paper. No. 470, p. 131). Rome: FAO. ISBN:92-5-105289-1.

Kennelly, S.J. (Ed.) (2016). Proceedings of the 8th international fisheries observer and monitoring conference, San Diego, USA (p. 349). ISBN:978-0-9924930-3-5.

Kennelly, S.J., & Borges, L. (Eds.) (2018). Proceedings of the 9th international fisheries observer and monitoring conference, Vigo, Spain (397 pp). ISBN:978-0-9924930-7-3.

Kindt-Larsen, L., Kirkegaard, E., Dalskov, J. (2011). Fully documented fishery: a tool to support a catch quota management system. ICES Journal of Marine Science, 68(8), 1606–1610.

Kindt-Larsen, L., Berg, C.W., Tougaard, J., Sørensen, T.K., Geitner, K., Northridge, S., et al. (2016). Identification of high-risk areas for harbour porpoise Phocoena phocoena bycatch using remote electronic monitoring and satellite telemetry data. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 555, 261–271.

Kraan, M., Uhlmann, S., Steenbergen, J., Van Helmond, A.T., Van Hoof, L. (2013), The optimal process of self-sampling in fisheries: Lessons learned in the Netherlandsa. Journal of Fish Biology, 83, 963–973. https://doi.org/10.1111/jfb.12192.

Lee, J., South, A.B., Jennings, S. (2010). Developing reliable, repeatable, and accessible methods to provide high-resolution estimates of fishing-effort distributions from vessel monitoring system (VMS) data. ICES Journal of Marine Science, 67(6), 1260–1271.

Liggins, G.W., Bradley, M.J., Kennelly, S.J. (1997). Detection of bias in observer-based estimates of retained and discarded catches from a multispecies trawl fishery. Fisheries Research, 32(2), 133–147.

Linchant, J., Lisein, J., Semeki, J., Lejeune, P., Vermeulen, C. (2015). Are unmanned aircraft systems (UASs) the future of wildlife monitoring? A review of accomplishments and challenges. Mammal Review, 45(4), 239–252.

Lordan, C., Cuaig, M., Graham, N., Rihan, D. (2011). The ups and downs of working with industry to collect fishery-dependent data: the Irish experience. ICES Journal of Marine Science, 68(8), 1670–1678.

Mangi, S.C., Smith, S., Armstrong, S., Catchpole, T.L. (2014). Self-sampling in the inshore sector (SESAMI). Final report, CEFAS, UK, p. 53.

Mangi, S.C., Dolder, P.J., Catchpole, T.L., Rodmell, D., Rozarieux, N. (2015). Approaches to fully documented fisheries: practical issues and stakeholder perceptions. Fish Fish, 16, 426–452. https://doi.org/10.1111/faf.12065

Mangi, S.C., Smith, S., Catchpole, T.L. (2016). Assessing the capability and willingness of skippers towards fishing industry-led data collection. Ocean & Coastal Management, 134, 11–19.

McElderry, H. (2006). At-Sea observing using video-based electronic monitoring (p. 25). ICES CM 2006/N:14.

McElderry, H., & Turris, B. (2008). Evaluation of monitoring and reporting needs for groundfish sectors in New England. Pacific fisheries management incorporated and Archipelago Marine Research Ltd., p. 68.

Miller, D.G.M., Slicer, N.M., Hanich, Q. (2013). Monitoring, control and surveillance of protected areas and specially managed areas in the marine domain. Marine Policy, 39, 64–71.

Mortensen, L.O., Ulrich, C., Olesen, H.J., Bergsson, H., Berg, C.W., Tzamouranis, N. et al. (2017). Effectiveness of fully documented fisheries to estimate discards in a participatory research scheme. Fisheries Research, 187:150–157.

Murawski, S.A., Wigley, S.E., Fogarty, M.J., Rago, P.J., Mountain, D.G. (2005). Effort distribution and catch patterns adjacent to temperate MPAs. ICES Journal of Marine Science, 62(6), 1150–1167.

Natale, F., Gibin, M., Alessandrini, A., Vespe, M., Paulrud, A. (2015). Mapping fishing effort through AIS data. PLoS One, 10(6), e0139746.

Needle, C., & Catarino, R. (2011) Evaluating the effect of real-time closures on cod targeting. ICES Journal of Marine Science, 68, 1647–1655.

Needle, C.L., Dinsdale, R., Buch, T.B., Catarino, R.M., Drewery, J., Butler, N. (2015). Scottish science applications of remote electronic monitoring. ICES Journal of Marine Science, 72(4), 1214–1229. https://doi.org/10.1093/icesjms/fsu225.

Nuevo, M., Morgado, C., Sala, A. (this volume). Monitoring the implementation of the Landing Obligation: Last Haul programme. In S.S. Uhlmann, C. Ulrich, S.J. Kennelly (Eds.), The European Landing Obligation – Reducing discards in complex, multi-species and multi-jurisdictional fisheries. Cham: Springer.

Óskarsdóttir, K., & Gunnlaugsson, V. (2015). Flæði gagna milli aðila í sjávarútveginum. Reykjavík: Matís.

Pennington, M., & Helle, K. (2011). Evaluation of the design and efficiency of the Norwegian self-sampling purse-seine reference fleet. ICES Journal of Marine Science, 68(8), 1764–1768.

Piovano, S. & Gilman, E. (2017). Elasmobranch captures in the Fijian pelagic longline fishery. Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems, 27(2), 381–393.

Plet-Hansen, K.S., Eliasen, S.Q., Mortensen, L.O., Bergsson, H., Olesen, H.J., Ulrich, C. (2018). Remote electronic monitoring and the landing obligation – some insights into fishers‘ and fishery inspectors‘ opinions. Marine Policy, 76, 98–106.

Porter, R.D. (2010). Fisheries observers as enforcement assets: Lessons from the North Pacific. Marine Policy 34(3), 583–589.

Roberts, J., Course, G., Pasco, G., Sandeman, L. (2015). Catch quota trials – South West Beam Trawl. Marine Management Organisation, London. 22 pp.

Rodríguez-Gutierrez, J., Castro, J., Salinas, I., Araujo, H., Marin, M. (2018). Improving protocol of selection of vessels to reduce bias. In Kennelly, S.J. & Borges, L. (Eds.) Proceedings of the 9th International Fisheries Observer and Monitoring Conference, Vigo, Spain (p. 397). ISBN:978-0-9924930-7-3.

Ruiz, J. (2013). Pilot study of an electronic monitoring system on a tropical tuna purse seine vessel in the Atlantic Ocean. Norwegian College of Fisheries Science: Master’s Degree Thesis in International Fisheries Management. Tromso: UiT, p. 59.

Ruiz, J., Krug, I., Gonzalez, O., Gomez, G., Urrutia, X. (2014). Electronic eye: Electronic monitoring trial on a tropical tuna purse seiner in the Atlantic Ocean. SCRS/2014/138. Collect Vol Science Papers ICCAT 71(1), 476–488, (2015).

Ruiz, J., Krug, I., Justel-Rubio, A., Restrepo, V., Hammann, G., Gonzalez, O., Legorburu, G., Alayon, P.J.P., Bach, P., Bannerman, P., GalÃn, T. (2016). Minimum standard for the implementation of electronic monitoring systems for the tropical tuna purse seine fleet. SCRS/2016/180. Collect Vol Science Papers ICCAT, 73(2), 818–828 (2017).

Russo, T., D’Andrea, L., Parisi, A., Martinelli, M., Belardinelli, A., Broccoli, F., et al. (2016). Assessing the fishing footprint using data integrated from different tracking devices: Issues and opportunities. Ecological Indicators, 69, 818–827.

Russo, T., Morello, E.B., Parisi, A., Scarcella, G., Angelini, S., Labanchi, L., et al. (2018). A model combining landings and VMS data to estimate landings by fishing ground and harbour. Fisheries Research, 199, 218–230.

Sandeman, L., Royston, A., Roberts, J. (2016). North Sea Cod catch quota trials: Final report 2015 (p. 38). London: Marine Management Organisation.

Selbe, S. (2014). Monitoring and Surveillance Technologies for Fisheries (p. 132). La Jolla: Waitt Institute.

Skaar, K.L., Jorgensen, T., Ulvestad, B.K.H., Engås, A. (2011). Accuracy of VMS data from Norwegian demersal stern trawlers for estimating trawled areas in the Barents Sea. ICES Journal of Marine Science, 68(8), 1615–1620.

Stanley, R.D., Karim, T., Koolman, J., McElderry, H. (2015). Design and implementation of electronic monitoring in the British Columbia groundfish hook and line fishery: a retrospective view of the ingredients of success. ICES Journal of Marine Science, 72(4), 1230–1236.

Starr, P. (2000). Fishery management innovations in New Zeal and New Zealand Seafood Industry Council (p. 6).

Ticheler, H., Kolding, J., Chanda, B. (1998). Participation of local fishermen in scientific fisheries data collection: A case study from the Bangweulu Swamps, Zambia. Fisheries Management and Ecology, 5(1), 81–92.

Ulrich, C., Olesen, H.J., Bergsson, H., Egekvist, J., Håkansson, K. B, Dalskov, J., et al. (2015). Discarding of cod in the Danish fully documented fisheries trials. ICES Journal of Marine Science, 72(6),1848−1860.

van Helmond, A.T.M., Chen, C., Poos, J.J. (2015). How effective is electronic monitoring in mixed bottom-trawl fisheries? ICES Journal of Marine Science, 72(4), 1192–1200.

van Helmond, A.T.M., Chen, C., Trapman, B.K., Kraan, M., Poos J.J. (2016). Changes in fishing behaviour of two fleets under fully documented catch quota management: Same rules, different outcomes. Marine Policy , 67, 118–129.

van Helmond, A.T.M., Chen, C., Poos, J.J. (2017). Using electronic monitoring to record catches of sole (Solea solea) in a bottom trawl fishery. ICES Journal of Marine Science, 74(5), 1421–1427. https://doi.org/10.1093/icesjms/fsw241.

Vilas, C., Antelo, L.T., Ordoñez, T., Pérez-Martín, R.I., Alonso, A.A., Valeiras, J. et al. (2018a). An Innovative Technology for On Board Automatic Identification and Quantification of the Catch. In: Proceedings of the international conference on advances in marine technologies applied to discard mitigation and management (MARTEC 18), Vigo, Spain.

Vilas, C., Antelo, L.T., Ordoñez, T., Pérez-Martín, R.I., Alonso, A.A., Valeiras, J. et al. (2018b). On board automatic identification and quantification of the total catch: The iObserver. In: Kennelly, S.J., & Borges, L. (Eds.), Proceedings of the 9th Fisheries Observer & Monitoring Conference (IFOMC), Vigo, Spain. ISBN:978-0-9924930-7-3. 395 pp.

Wallace, F., Faunce, C., Loefflad, M. (2013). Pressing rewind: A cause for a pause on electronic monitoring in the North Pacific. ICES CM 2013/J:11.

Zeller, D., Cashion, T., Palomares, M., Pauly, D. (2018). Global marine fisheries discards: A synthesis of reconstructed data. Fish Fish, 19, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1111/faf.12233

Acknowledgments

This chapter is largely based on work carried out in the DiscardLess project and the Life iSEAS project. The DiscardLess project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement DiscardLess No 633680. The Life iSEAS project has been co-funded under the LIFE+Environment Program of the European Union (LIFE13 ENV/ES/000131). This support is gratefully acknowledged. Authors also want to thank Ms. Esther Abad, Mr. Xesºs Morales, Ms. Marta QuinzÃn and Mr. Julio Valeiras for their contribution to the development of the iObserver.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2019 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

James, K.M. et al. (2019). Tools and Technologies for the Monitoring, Control and Surveillance of Unwanted Catches. In: Uhlmann, S., Ulrich, C., Kennelly, S. (eds) The European Landing Obligation. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-03308-8_18

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-03308-8_18

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-03307-1

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-03308-8

eBook Packages: Biomedical and Life SciencesBiomedical and Life Sciences (R0)