Abstract

Compared to other major food crops, progress in potato yield as the result of breeding efforts is very slow. Genetic gains cannot be fixed in potato due to obligatory out-breeding. Overcoming inbreeding depression using diploid self-compatible clones should enable to replace the current method of out-breeding and clonal propagation into an F1 hybrid system with true seeds. This idea is not new, but has long been considered unrealistic. Severe inbreeding depression and self-incompatibility in diploid germplasm have hitherto blocked the development of inbred lines. Back-crossing with a homozygous progenitor with the Sli gene which inhibits gametophytic self-incompatibility gave self-compatible offspring from elite material from our diploid breeding programme. We demonstrate that homozygous fixation of donor alleles is possible, with simultaneous improvement of tuber shape and tuber size grading of the recipient inbred line. These results provide proof of principle for F1 hybrid potato breeding. The technical and economic perspectives are unprecedented as these will enable the development of new products with combinations of useful traits for all stakeholders in the potato chain. In addition, the hybrid’s seeds are produced by crossings, rendering the production and voluminous transport of potato seed tubers redundant as it can be replaced by direct sowing or the use of healthy mini-tubers, raised in greenhouses.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Genetic yield progress accomplished by breeders of major field crops like maize, soybean, rice and wheat is approx. 1% per year (Duvick 2005). The reason that century old potato varieties such as Russet Burbank and Bintje are still cultivated is the lack of major genetic improvement in potato. This slow progress in potato breeding is illustrated by the many potato cultivars still lacking adequate levels of disease resistances, although these traits are needed and available in the potato germplasm. Traditional potato breeding for quantitative traits is mainly executed using phenotypic selection because the identification and mapping of genes involved in these quantitative traits have not yet resulted in validated genetic markers (Bradshaw et al. 2007; Li et al. 2010).

As a result of the traditional way of potato breeding, unfavourable alleles easily remain “hidden” in the tetraploid genome and become manifest at each breeding cycle. It takes large selection programmes on progeny plants derived from crosses between tetraploid potato cultivars to select a clone that has the right balance between unfavourable alleles and compensating alleles at the same or at other loci. Typically, it takes about 100,000 seedlings to generate one new variety. And still such a variety may contain numerous “masked” or “hidden” unfavourable alleles. As a consequence, the genetic gain in breeding is very limited. In order to achieve continuous progress in potato breeding, an alternative system should be developed that is based on the structural removal of unfavourable alleles. This is most efficiently achieved at the diploid (or even haploid) level as the chance that unfavourable alleles are homozygously present is much higher in diploids than in tetraploids. Such genes may be identified and eliminated in a breeding programme based on selfed generations.

Severe inbreeding depression and self-incompatibility in diploid germplasm have hitherto blocked the development of inbred lines in potato. However, there are no theoretical reasons why homozygotes could not be obtained in any crop. In some crops like leek and carrot, completely homozygous lines are still barely used as their performance is too weak for efficient hybrid seed production. In other crops, such as maize and beet, successful F1 hybrid breeding has been achieved by consistent breeding for high-performing inbred lines (Crow 1998).

The ideas of hybrid potato breeding go back more than 50 years ago (Hawkes 1956) and saw a revival during the onset of cell biology techniques in potato, about 30 years ago. Several studies reported the successful generation of haploid and dihaploid potato plants (De Jong and Rowe 1971; Van Breukelen et al. 1977; Uijtewaal et al. 1987; Chani et al. 2000) and the expectations for breeding pure lines were quite high. However, no progress has been reported in the generation of homozygous potato clones with acceptable agronomic performance. Why did the results of these studies not flow into practical breeding programmes? Most likely, the genetic variation, in a tetraploid crop, always embraced by breeders has been too high: The average number of different alleles per locus in tetraploid potato is 3.2 and at least ten alleles per locus are present in the commercial potato germplasm (Uitdewilligen et al. 2011). Although this represents a rich reservoir of useful alleles, it will inevitably also harbour alleles with negative effects. Breeders therefore rely for their success on a numbers game, as they usually raise about 100,000 seedlings to generate one new variety. Such a variety will still contain numerous unfavourable alleles. The main activity of a breeder is to select the best clone using phenotypic evaluations, while he is devoid of tools and knowledge with respect to the alleles that should be fixed or removed from the gene pool. This is the most important reason why the progress in potato breeding is very limited.

As a consequence of the high level of unfavourable alleles, techniques aimed at developing homozygotes in one step, although successful as a technology in various crops, certainly do not generate vigorous homozygous potatoes. For instance, if 20 of the 39,000 protein-encoding genes (PGSC 2011) on the potato genome harbour alleles causing severe fitness reduction, the chance to generate vigorous diploid selfed progenies without homozygous unfavourable loci from a parent genotype, that is heterozygous for these 20 loci, is only 0.3%. Obviously, tetraploids are much more tolerant for alleles with unfavourable effects as the chance to get a completely homozygous locus is far lower than for diploids. In conclusion, traditional tetraploid potato breeding allows the maintenance of a high abundance of unfavourable alleles.

No example is known of a tetraploid vegetatively propagated crop that has been converted into a diploid F1 hybrid crop. Usually, commercial potato varieties are tetraploid. In the Andean Centre of Origin of potato, still diploid varieties are cultivated, but these are preliminary landraces (Spooner et al. 2007), while incidentally diploid varieties are used in Europe and USA, mainly from Solanum phureja origin. At Wageningen University, a diploid breeding programme already runs for some decades (Hutten 1994). This breeding programme comprises variation for yield, tuber quality traits and resistances. Diploids usually have lower yields than tetraploids, although some diploids may outyield tetraploid standards (Hutten 1994). This yield gap between diploids and tetraploids may be bridged by breeding at the diploid level as this is still in its infancy. Studies on differences between related diploids and tetraploids have not been conclusive while there is much overlap in characters between diploids and tetraploids (Hutten et al. 1994; Spooner et al. 2007). As breeding at the diploid level is more efficient than at the tetraploid level, an efficient breeding programme may be executed at the diploid level while tetraploid F1 hybrids may be generated by oryzalin treatment of diploid parents or from diploid crosses by using unreduced gametes (Carputo et al. 2000; Chauvin et al. 2003).

Diploids are usually self-incompatible, prohibiting selfing that is needed to generate and maintain homozygous lines. Hosaka and Hanneman (1998a, b) reported about the Sli gene originating from Solanum chacoense that renders diploid potato self-compatible. They used repeated selfings to generate homozygous genotypes (Phumichai et al. 2005; Phumichai and Hosaka 2006; Phumichai et al. 2006). These homozygous clones showed poor agronomic performance as tuber quality and yield were extremely low. This could be considered as evidence for severe inbreeding depression in potato, and that inbreds will never have commercial value (Uijtewaal et al. 1987; Almekinders et al. 2009). However, in our opinion, the combination of a wide diploid germplasm with much allelic variation and this Sli gene are the crucial elements for a breeding programme aimed at selecting for inbreeding tolerance.

The present paper describes results, which demonstrate the feasibility of an F1 hybrid potato-breeding method. We started with the introduction of the Sli gene into elite diploid germplasm. The F1 progenies were selfed and the resulting F2 progenies were selected for self-compatibility, vigorous growth, tuber quality and yield. Single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) markers, well distributed over the potato genome, were applied to study the segregation of genetic loci and the level of homozygosity in parents and offspring. In this way, inbred lines were developed that combined self-compatibility with good agronomic performance. Although the number of such plants is still low, the progress made in this breeding programme is significant. Several self-compatible F3 plants with more than 80% homozygous loci were crossed to generate a first prototype of an F1 hybrid variety. The impact of these results on potato breeding, potato seed production, processing and consumption is discussed.

Materials and Methods

Materials

The Sli gene donor was kindly donated by Dr. K. Hosaka, National Agriculture Research Center for Hokkaido Region, Hokkaido, Japan and designated as DS (donor of Sli gene). The two other clones are from the laboratory of Plant Breeding of Wageningen University called IVP97-079-9 and IVPAA-096-18; for the sake of convenience, we designate these clones as D1 and D2, respectively.

Crosses, Progenies and Field Tests

D1 and D2 were crossed with DS, generating F1 progenies, which were subsequently selfed yielding F2 populations (Table 1). The crossing plants were grown in the winter in a greenhouse with artificial light and heating. Some self-compatible F2 plants were selfed and F3 progenies were collected.

In addition, the seeds of F2 populations were sown in a greenhouse with the day/night temperature set at 20/10 °C. Three weeks after sowing, the seedlings were transplanted into seedling trays and the young plants were transplanted into two trial fields; one with clay soil in Hazerswoude and one with sandy soil in Hoeven, both in The Netherlands. At the middle of the flowering period, plants were scored for spontaneous berry set in the field. Per population, the best plants with good berry set and plant performance were selected and selfed seeds were obtained. At the end of the growing season, all plants were scored for tuber quality and yield. The selfed (F3) seeds, originating from underperforming plants, were discarded.

Two hundred sixty-five random plants of six F3 populations (three of D1 × DS and three of DS × D2) were grown in the greenhouse and tested for segregation of markers and homozygosity/heterozygosity levels. To this end, a subset was selected per F3 population of 24 informative SNP markers derived from the 100 PotSNP marker loci (Anithakumari et al. 2010) covering all 24 chromosome arms of potato. DNA extractions were done using Klear Gene DNA Extraction Kits and PotSNP marker analyses by KASP SNP genotyping system (http://www.kbioscience.co.uk).

F3 plants, grown in the greenhouse and in the field, were evaluated for self-compatibility. Self-compatible F3 plants, originating from D1 × DS and DS × D2, were crossed to generate prototype F1 hybrids.

In addition, a small subset of 46 F3 plants was grown in winter in the greenhouse in two-liter pots and hand pollinated to stimulate fruit set and F4 seeds were harvested. Next spring, these F3 and F4 populations were planted in the field (Fig. 1).

Results

Introduction of the Sli Gene into Potato Germplasm

To study the transmission of the Sli gene into diploid elite germplasm, crosses were made between two elite clones (designated “D1” and “D2”) and the Sli donor (designated “DS”; Table 1). The progeny F1s were selfed and F2 and F3 populations were generated and analysed. The F1s were more than 50% self-compatible. F2 plants were grown and flowers were hand pollinated. Thirteen F2 plants with good pollen segregated into ten self-compatible and three self-incompatible plants. These results were not in conflict with a genetic hypothesis of one dominant Sli gene rendering self-compatibility into diploid potato.

Segregation of F3 progenies

We analysed the segregation of 24 informative markers over 265 plants of six F3 populations. Most markers showed homozygous loci, according to expectation in an F3 population. The homozygote frequencies of all loci per population ranged from 84% to 94% and per plant from 71% to 100%. The range of the expected level of homozygosity in F3 populations reflects the genotypes of the D1 and D2 parent (AA × BB or AA × AB). Remarkably, six plants were identified that were already 100% homozygous, given these 24 marker loci. Although there may be heterozygotic chromosome regions that have escaped our detection with on average one marker per chromosome arm, it still indicated that high levels of homozygosity were reached.

Three to eight markers segregated in the six F3 populations. The other markers were already homozygous in the F2 and did not segregate in the F3 (not shown). In total, 12 markers showed distorted segregation ratios that significantly deviated from expected monogenic inheritance. Usually, marker genotypes, homozygous for the non-DS parent, were underrepresented. These marker loci may represent loci with alleles, with a negative effect on plant fitness. Only one marker or locus showed extreme skewness as only one plant was identified with homozygous PotSNP100 donor alleles over 143 plants tested. The plant tuber yield of the F3 plants ranged from very low to more than 1 kg per plant, well within the range of their parent clones (Fig. 2).

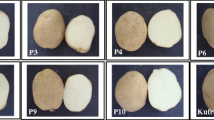

Tuber quality and yield from three individual F3 plants. The top panel shows the parent clones: the Sli donor on the left and the D2 parent clone on the right. The bottom panel shows three random F3 progeny plants from crosses between the parent clones. The homozygosity percentages were, from left to right: 100%, 86% and 83%, respectively. The total tuber yield of the plant at the right hand panel was close to 1,300 g

The First F1 Hybrid Prototypes

Most of the F3 plants were self-incompatible. Spontaneous self-compatible F3 plants were selected and F3 progenies from D1 × DS were crossed with F3 plants from the DS × D2 cross. These F3 plants showed at least 83% homozygous loci. F1 plants were raised as potted plants in a winter nursery. Although the parent F3 plants for this pilot experiment were only selected for self-compatibility, the F1 plants showed remarkable uniformity with good tuber quality and yield in this greenhouse environment, which was in a range similar to that of other diploid clones from crosses between non-inbred parents (results not shown). This provided evidence about the feasibility of F1 hybrid breeding in potato (Fig. 3).

The first prototype F1 hybrids. On the left, four different self-compatible F3 clones (D1 × DS) are shown. These were crossed with the same individual F3 plant (DS × D2) from the field that showed similar tubers as the DS parent (see Fig. 2). These crosses resulted in F1 hybrid prototypes that are indicated in the middle and right column. Note the remarkable uniform and high-quality tubers of the third F1 hybrid prototype

Breeding Programme

The development and testing of materials generated so far were executed to get proof of principle for F1 hybrid potato breeding. However, the plant performance and tuber characteristics were often still far from commercial standards. Therefore, we started a breeding programme aimed at developing self-compatible inbreds with good plant and tuber performance. In a summer field trial, F2 plants were grown and analysed for self-compatibility. Fifty-three F2 populations comprising 30 to 840 plants per family, in total 9,660 plants, were evaluated. Most of the populations showed a weak plant growth and a low frequency of self-compatibility. The progenies from the DS × D2 cross showed the best performances. In total, 29 F2 populations were tested and only 51 plants were selected that showed a combination of good plant performance, self-compatibility, tuber quality and yield (Table 1). In the following winter, 46 F3 plants were propagated in the greenhouse to F4. The latter were planted in the field and some populations also showed good fertility and some fruit set (Fig. 4).

Discussion

In this paper, we provide evidence that F1 hybrid seed breeding in potato is feasible. Inbred progenies have been obtained that combine a high level of homozygosity with good plant performance and good tuber quality and yield. Most importantly, F1 hybrids have been obtained by crossing highly homozygous inbred lines. These F1 hybrids were uniform and showed good tuber quality. This proof of principle has been substantiated by using SNP markers well distributed over the potato genome. Our results clearly show the abundance of genetic variation in potato as well as the segregation of genetic loci in various progenies. Remarkably, we did not observe absolute proof for a lethal allele, although many loci were found with distorted segregations, often in more than one population. Obviously, 24 markers do not cover all genetic loci and some chromosomes were not well represented by markers. So, some lethal allele may have escaped detection. In conclusion, lethal alleles do not occur at high frequency in our diploid potato germplasm. This offers good perspectives for breeding.

Still a Long Way Towards Commercial Products

Only a small fraction of the progeny plants combined self-compatibility with reasonable plant and tuber performance. Obviously, there are many loci with minor effects involved in these traits (Quantitative Trait Locus, QTL). Our current research focuses on identifying the crucial QTLs for these traits. The results will be applied in breeding and allow to increase efficiencies by using diagnostic markers for these traits. In addition, modern potato varieties are tailored to various markets for fresh consumption or processing with their typical requirements. It will still take many generations of breeding before commercial F1 hybrid cultivars are developed and released.

New Breeding Goals

The implementation of the F1 hybrid potato breeding technology will result in a completely new potato breeding system with a new breeding germplasm. From a breeding point of view, this can be considered as a completely new crop. For instance, enrichment of existing parent lines can be achieved by repeated backcrosses. This can be done in few years, with the great advantage that most of the traits, including processing traits, are already known and will remain unaltered. More importantly, traits can be stacked. This will take 1 or 2 years more and offers great advantages to develop suitable varieties for specific markets with similar performance but with a series of different additional traits (e.g., disease resistances). Breeding germplasm of potato comprises sufficient genetic variation to serve specific market niches. The fresh consumption market requires both firm and mealy types. Processing demands cultivars that resist cold storage and round tubers for crisps and long tubers for French fries. At this moment, there is hardly a rational strategy to specifically breed for these market niches. In due time, it is anticipated that groups of inbred lines can be developed that combine traits like yield and pathogen resistance with market-specific quality traits. In addition, neglected traits may receive more attention such as resistance to bacterial diseases (Dickeya spp.) and root knot nematodes (Meloidogyne spp.), abiotic stress resistance (heat, frost, drought and salinity) and input use efficiency. As a consequence of these developments and opportunities, the breeders’ tool box to react on market opportunities with completely new products is impelling. This advanced way of breeding is characterised by building and improving specific genetic populations and using advanced breeding tools based on state of the art research results embedded in a traditional setting of skilled breeders. This will completely change the way of potato breeding and is hence considered as a paradigm shift.

New Research Opportunities

The paradigm shift in breeding coincides with a paradigm shift in research. Scientific research programmes in potato already benefit from detailed physical and genetic maps and full genome sequences (Van Os et al. 2006; PGSC 2011). Homozygous potato lines will enable the generation of recombinant inbred lines, near isogenic lines and introgression libraries, which have proven to be extremely useful for forward genetics in other crops like tomato, barley and lettuce, as well as in Arabidopsis (Fridman et al. 2004). These genetic tools will greatly support the identification, mapping, isolation and functional analysis of useful genes that contribute to the genetic improvement of potato.

We anticipate a revival in forward genetics, as soon as well-defined homozygous genetic stocks and near isogenic lines allow the identification and stacking of alleles that contribute to yield and quality (Semel et al. 2006; Tan et al. 2010). Marker-assisted selection of favourable alleles enables the incremental improvement of the recipient homozygous and self-compatible inbred lines at a speed of two to three generations per year. Yield progress is not necessarily expected already from inbreds, but hybrid vigour of F1 hybrids will contribute to yield progress (Hua et al. 2003). Earlier examples such as maize show that hybrid vigour can partially be fixed in improved inbreds, but heterosis will remain an additional component in yield progress (Birchler et al. 2010).

We still lack fundamental knowledge on the performance of diploids versus tetraploids. At this moment, commercial tetraploids perform better than diploids, but this may be due to the limited breeding efforts in diploids versus tetraploids. If the removal of unfavourable alleles in diploid potato is successful, diploids may eventually outperform tetraploids. The other top three world staple crops, rice, wheat and corn, are all cultivated as diploids, while a crop like sugar beet has been converted from tetra, via tri- to diploid crop. As long as the underlying mechanisms of the phenotype changes in polyploid crops are unknown, plant performance at various ploidy levels should be empirically tested and the results applied in practice (Carputo and Barone 2005).

The F1 Hybrid System Allows High Multiplication Rates Without Clonal Propagation

The traditional clonal multiplication rate achieved with seed potatoes is only a factor of 10 and is constrained by the accumulation of pathogens, physiological decline and high costs for storage and transport. In contrast, one plant can easily produce thousands of F1 hybrid seeds. These seeds can be sown directly in the field or grown to produce disease-free mini-tubers in nurseries depending on local climate and logistic infrastructure. Hybrid seed production can be optimised through, e.g. cytoplasmic male sterility or self-incompatibility. Clonal propagation of tubers from F1 hybrid potatoes will still remain feasible as an alternative for farmers preferring Farmers Saved Seed systems.

In future, efficient production systems for potato seed have to be established. Most likely, that will greatly resemble seed production systems in vegetable crops, whereby phytosanitation, seed security and quality, etc. are crucial elements. The great advantage is that the most suitable locations wherever in the world can be chosen to produce the true potato seeds as transportation and storage costs are minimal as compared to seed tubers of potato.

References

Almekinders CJM, Chujoy E, Thiele G (2009) The use of true potato seed as pro-poor technology: the efforts of an international agricultural research institute to innovating potato production. Potato Res 52:275–293

Anithakumari AM, Tang J, Van Eck HJ, Visser RGF, Leunissen JA, Vosman B, Van der Linden CG (2010) A pipeline for high throughput detection and mapping of SNPs from EST databases. Mol Breed 26:65–75

Birchler JA, Yao H, Chudalayandi S, Vaiman D, Veitia RA (2010) Heterosis. Plant Cell 22:2105–2112

Bradshaw JE, Hackett CA, Pande B, Waugh R, Bryan GJ (2007) QTL mapping of yield, agronomic and quality traits in tetraploid potato (Solanum tuberosum subsp. tuberosum). Theor Appl Genet 116:193–211

Carputo D, Barone A (2005) Ploidy level manipulations in potato through sexual hybridisation. Ann Appl Biol 146:71–79

Carputo D, Barone A, Frusciante L (2000) 2n gametes in the potato: essential ingredients for breeding and germplasm transfer. Theor Appl Genet 101:805–813

Chani E, Veilleux RE, Boluarte-Medina T (2000) Improved androgenesis of interspecific potato and efficiency of SSR markers to identify homozygous regenerants. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult 60:101–112

Chauvin JE, Souchet C, Dantec JP, Ellissèche D (2003) Chromosome doubling of 2x Solanum species by oryzalin: method development and comparison with spontaneous chromosome doubling in vitro. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult 73:65–73

Crow JF (1998) 90 years ago: the beginning of hybrid maize. Genetics 148:923–928

De Jong H, Rowe PR (1971) Inbreeding in cultivated diploid potatoes. Potato Res 14:74–83

Duvick DN (2005) The contribution of breeding to yield advances in maize (Zea mays L.). Adv Agron 86:83–145

Fridman E, Carrari F, Liu YS, Fernie AR, Zamir D (2004) Zooming in on a quantitative trait for tomato yield using interspecific introgressions. Science 305:1786–1789

Hawkes JG (1956) Potato breeding in Russia—July, 1956. Euphytica 6:38–44

Hosaka K, Hanneman RE (1998a) Genetics of self-compatibility in a self-incompatible wild diploid potato species Solanum chacoense. 1. Detection of an S locus inhibitor (Sli) gene. Euphytica 99:191–197

Hosaka K, Hanneman RE (1998b) Genetics of self-compatibility in a self-incompatible wild diploid potato species Solanum chacoense. 2. Localization of an S locus inhibitor (Sli) gene on the potato genome using DNA markers. Eutphytica 103:265–271

Hua J, Xing Y, Wu W, Xu C, Sun X, Yu S, Zhang Q (2003) Single-locus heterotic effects and dominance by dominance interactions can adequately explain the genetic basis of heterosis in an elite rice hybrid. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100:2574–2579

Hutten RCB (1994) Basic aspects of potato breeding via the diploid level. Thesis, Wageningen University, Wageningen, ISBN 9054852925

Hutten RCB, Schippers MGM, Hermsen JGTh, Jacobsen E (1994) Comparative performance of diploid and tetraploid progenies from 2x.2x crosses in potato. Euphytica 81:187–192

Li L, Paulo M-J, Van Eeuwijk F, Gebhardt C (2010) Statistical epistasis between candidate gene alleles for complex tuber traits in an association mapping population of tetraploid potato. Theor Appl Genet 121:1303–1310

PGSC (2011) Genome sequence and analysis of the tuber crop potato. Nature 475:189–194

Phumichai C, Hosaka K (2006) Cryptic improvement for fertility by continuous selfing of diploid potatoes using Sli gene. Euphytica 149:251–258

Phumichai C, Mori M, Kobayashi A, Kamijima O, Hosaka K (2005) Toward the development of highly homozygous diploid potato lines using the self-compatibility controlling Sli gene. Genome 48:977–984

Phumichai C, Ikeguchi-Samitsu Y, Fuijmatsu M, Kitanishi S, Kobayashi A, Mori M, Hosaka K (2006) Expression of S-locus inhibitor gene (Sli) in various diploid potatoes. Euphytica 148:227–234

Semel Y, Nissenbaum J, Menda N, Zinder M, Krieger U, Issman N, Pleban T, Lippman Z, Gur A, Zamir D (2006) Overdominant quantitative trait loci for yield and fitness in tomato. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103:12981–12986

Spooner DM, Núñez J, Trujillo G, del Rosario HM, Guzmán F, Ghislain M (2007) Extensive simple sequence repeat genotyping of potato landraces supports a major reevaluation of their gene pool structure and classification. Proc Natl Acad Soc U S A 104:19398–19403

Tan MYA, Hutten RCB, Visser RGF, Van Eck, HJ (2010) The effect of pyramiding Phytophthora infestans resistance genes R (Pi-mcd1) and R (Pi-ber) in potato. Theor Appl Genet 121:117–125

Uijtewaal BA, Jacobsen E, Hermsen JGTh (1987) Morphology and vigour of monohaploid potato clones, their corresponding homozygous diploids and tetraploids and their heterozygous diploid parent. Euphytica 36:745–753

Uitdewilligen JGAML, Wolters A-M, Van der Vlies P, Visser RGF, Van Eck HJ (2011) SNP and haplotype identification from targeted next-generation re-sequencing in a set of 83 potato cultivars The 18th Triennial Conference of the European Association for Potato Research, Oulu, Finland, July 24–29, 2011 (Abstract book p 97)

Van Breukelen EWM, Ramanna MS, Hermsen JGTh (1977) Pathenogenetic monohaploids (2n = 2x = 12) from Solanum tuberosum L. and S. verrucosum Schlechtd. and the production of homozygous potato diploids. Euphytica 26:263–271

Van Os H, Andrzejewski S, Bakker E, Barrena I, Bryan GJ, Caromel B, Ghareeb B, Isidore E, De Jong W, Van Koert P, Lefebvre V, Milbourne D, Ritter E, Rouppe van der Voort JNAM, Rousselle-Bourgeois F, Van Vliet J, Waugh R, Visser RGF, Bakker J, Van Eck HJ (2006) Construction of a 10,000-marker ultradense genetic recombination map of potato: providing a framework for accelerated gene isolation and a genomewide physical map. Genetics 173(2):1075–1087

Acknowledgements

Dr. K. Hosaka (National Agriculture Research Center for Hokkaido Region, Hokkaido, Japan) is greatly acknowledged for providing the Sli gene-harbouring potato clones. The families of the co-founders of Solynta, Hein Kruyt, Theo Schotte, Johan Trouw and Pim Lindhout, are greatly acknowledged for their continuous trust in and support to the development of this F1 hybrid method.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Lindhout, P., Meijer, D., Schotte, T. et al. Towards F1 Hybrid Seed Potato Breeding. Potato Res. 54, 301–312 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11540-011-9196-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11540-011-9196-z