Abstract

Large changes in biodiversity are expected to occur if climate change continues at its current pace. Adverse effects include changes in species habitats and compositions, and consequently changes in ecosystem functioning. We assessed the magnitude of expected changes of biodiversity by performing a meta-analysis of the responses of species distributions to climate change. We focused on the proportion of local remaining species and their habitats. We summarized 97 studies and calculated two effect-size metrics from their results to quantify changes in biodiversity. These metrics are the fraction of remaining species (FRS) and the fraction of remaining area (FRA) with suitable climate for each species. Both metrics calculate deviations from the original biodiversity state and together they indicate biodiversity intactness. We found an expected gradual decrease in both FRS and FRA with significant reductions of 14% and 35% between 1 and 2 °C increase in global mean temperatures. Strong impacts are projected for both mammals and plants with FRS reductions of 19%. The climate-change response of biodiversity varies strongly among taxonomic groups and biomes. For some taxonomic groups the FRA declines strongly beyond 3 °C of temperature increase. Although these estimates are conservative, as we assume that species are unable to disperse or adapt, we conclude that already at moderate levels (i.e., 1–2 °C) of temperature increase a significant decrease of original biodiversity is projected. Our research supports the pledge to limit climate change to 1.5 °C and preferably lower to protect biodiversity.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Biodiversity is under increasing threats by many anthropogenic pressures (Alkemade et al. 2009; Leadley et al. 2014; Tittensor et al. 2014; Visconti et al. 2015; Johnson et al. 2017; Ripple et al. 2017). A major pressure of biodiversity decline in this century is climate change (Parmesan and Yohe 2003; Thomas et al. 2004; Warren et al. 2011; Bellard et al. 2012; Pacifici et al. 2015; Urban 2015). Climate change affects biodiversity as climate variables largely determine the geographical distribution ranges of species (i.e., species’ climate envelopes; Box 1981; Guisan and Zimmermann 2000; Pearson and Dawson 2003). Hence, in areas where climate is no longer suitable, species shift their geographical ranges and go extinct locally, depending on their dispersal capacities (Guisan and Zimmermann 2000; Bellard et al. 2012). Species’ phenology and physiology and community structures and ecosystem functions are also affected (Bellard et al. 2012). All these negative impacts exacerbate the challenge to manage and conserve biodiversity (CBD 2019).

The average global temperature has increased by almost 1 °C since 1880, and the adverse effects of such increase on biodiversity are already witnessed and documented by many studies (Thomas et al. 2004; Parmesan 2006; Butchart et al. 2010; Cardinale et al. 2012; Cook et al. 2012; IPCC 2013; Peñuelas et al. 2013; sCBD 2014; Pacifici et al. 2017; Pecl et al. 2017). They all show that the decline of biodiversity continues worldwide as many ecosystems lose suitable conditions for the survival of a proportion of their species. Some studies project the already observed negative impacts on species (e.g., Parmesan et al. 2013; Warren et al. 2013), and their results feed into the ongoing debate of constraining the increase of global temperatures (e.g., by the climate-change target to keep global temperature increase well below 2 °C above pre-industrial levels in the Paris Agreement (UNFCCC 2015; Rogelj et al. 2018)). Yet, how biodiversity will respond to a global mean temperature increase of 2 °C, or any increase close to this target, is not yet clear and represents a fundamental research challenge.

The primary objective of this study is to quantify the response of terrestrial biodiversity to climate change covering global mean temperature increase up to 6 °C in 2100 (and implicitly considering associated climate variables, such as precipitation change) above the pre-industrial level. For this purpose, we performed a meta-analysis of studies that used bioclimatic models and climate-change scenarios. These studies reported climate-change effects on contemporary ecosystems and different taxonomic groups around the world. The climate-change level in these studies was indicated by their scenario’s global mean temperature increase. Most climate-change scenarios project that global mean temperature continues to increase to between 2 and over 5 °C in 2100 (Kintisch 2009; Moss et al. 2010; IPCC 2013; Rogelj et al. 2018). Similar to previous modeling studies that assessed the overall decline of biodiversity (e.g., Alkemade et al. 2009), we focused on the proportion of remaining biodiversity. We calculated two effect metrics: the fraction of remaining (i.e., persisting) species (FRS) at a location and the fraction of remaining area (FRA) with suitable climate for species. These metrics assess the changes of species richness over a region compared to the original situation in the selected study. Both metrics indicate a deviation from the original biodiversity state and indicate biodiversity intactness (Scholes and Biggs 2005; Alkemade et al. 2009). FRS indicates a decrease of species within the study region. FRA indicates a suitable climate-area (e.g., habitat) contraction within the study region. A potential increase of species or extending its geographical range is excluded from these metrics. As a result, FRS and FRA generally indicate a decline regardless of the global temperature interval. The changes in species composition can also indicate consequences for ecosystem’s functioning, but we do not address this. The results of our meta-analysis allow to generalize projected trends and to assess effects across a broad range of climate-change projections. The established meta-regression models can be used in models, such as the GLOBIO model (Alkemade et al. 2009; Alkemade et al. 2011), to assess biodiversity change in scenario studies in combination with other pressures of global biodiversity loss.

2 Methods and materials

2.1 Systematic literature review

In June 2016, we queried the ISI Web-of-Science database to identify bioclimatic modeling studies that assess the effects of global mean temperature increase on terrestrial biodiversity. We reviewed all studies following the guidelines provided by the Collaboration for Environmental Evidence (CEE) (CEE 2013) (see Online Resource 1 for a detailed description of the process). The guidelines indicate the stages for conducting a systematic research in environmental science, and these stages were combined into three main steps.

Firstly, we defined several search terms and classified them into four main search strings to conduct the review: (i) Climate change elements: (climat* SAME change*) OR (temperature SAME change*) OR (temperature SAME increase) OR (global SAME warming) OR (climat* SAME warming); (ii) biodiversity elements: (biodiversity) OR (diversity SAME species) OR (species SAME richness*) OR (species SAME distribution*) OR (species SAME abundance*) OR (species SAME occurrence*) OR (species SAME turnover) OR (species SAME loss*) OR (species SAME gain*) OR (species SAME composition) OR (species SAME assemblage*); (iii) bioclimatic modeling elements: (bioclimat* model*) OR (niche* model*) OR (climat* model*) OR (distribution model*) OR (habitat model*) OR (ecologic* model*) OR (occurrence model*) OR (species distribution model*) OR (model* distribution*) OR (model* range*) OR (climat* envelope*) OR (envelope* model*); and (iv) modeling projection elements: (future SAME distribution*) OR (climat* SAME scenario*) OR (climat* SAME projection) OR (climat* SAME prediction) OR (climat* SAME pathway*). Additionally, we defined seven inclusion criteria to determine the pertinence of the studies (see criteria in Online Resource 1). These criteria allowed to further restrict the selection by rejecting those studies that did not support our objective. All studies were screened by title for their relevance to the purpose of our study. Those studies selected were then screened by abstract and, when providing limited information in their abstracts, were fully screened, both in content and supporting material. Secondly, the potentially relevant studies were critically revised to select those fulfilling the inclusion criteria. Finally, the relevant data were extracted from all selected studies and synthesized in a biodiversity-impact database. These data included number of species and their area with suitable climate in the original and the projected climate situations, taxonomic group, study location, spatial resolution, and the used global mean temperature increase. Many studies that reported climate effects on single species or exotic species (particularly weeds and insect pests, and aquatic species) were excluded from the database. These studies do not provide data on the original species composition or do not consider terrestrial species.

2.2 Calculation of effect sizes

We calculated the effect sizes, which are measures commonly used in meta-analyses, for each selected study. For studies that assessed the number of species affected by increasing temperatures, we used the fraction of species remaining at a location (fraction remaining species (FRS) as the effect size; for studies assessing the loss of area with suitable climate for a species, we used the fraction of remaining area with suitable climate (fraction remaining area (FRA)) under a projected increase of global mean temperature (Fig. 1). Both FRS and FRA are effect sizes compared to the original situation in the selected study. The original situation refers to the ecosystem’s condition before its climate changed (i.e., original area with suitable climate). Results from multiple climate-change scenarios and time periods, or different bioclimatic modeling algorithms (e.g., generalized linear model, generalized additive model, maximum entropy modeling) that are reported in a study, were all included as separate effect sizes in our database.

We specifically estimated the proportion of remaining biodiversity (i.e., a conservative option assuming that species are unable to disperse or adapt) for three main reasons: (i) on average, the projected climate distributions of species are closer to projections without dispersal than projections with full dispersal (Midgley et al. 2006; Hellmann et al. 2016); (ii) uncertainty associated to the capacity of species to disperse (Pearson and Dawson 2003; Pearson et al. 2006) or adapt (Berry et al. 2013) under climate change is reduced; and (iii) FRS and FRA fit into the domain of the GLOBIO model, more specifically, they relate to the relative Mean Species Abundance (MSA) indicator from GLOBIO (Alkemade et al. 2009) and the Biodiversity Intactness Index (BII) (Scholes and Biggs 2005; Newbold et al. 2016) of the local remaining biodiversity.

FRS is calculated as average of ratios between the remaining number of species and the original number of species within each locality (e.g., a grid cell) of the study area’s map after projected climate change:

where Sdi is the expected number of remaining species in grid cell i after climate change as characterized by global mean temperature increase (°C) and Soi is the number of species in grid cell i in the original situation. n is the total number of grid cells. FRS is a relative index between 0 (no original species present) and 1 (all original species present). FRS decreases if the climate is not suitable anymore for a species at one of the grid cells within the study area. FRS represents the local response of species to climate change (e.g., in a specific grid cell).

FRA is calculated per species as the ratio between the original suitable climate area and the remaining suitable climate area:

where Adj is the remaining suitable climate area for species j after climate change, Aoj is the suitable climate area for species j in original situation without climate change, and S is the number of species. FRA is also a relative index between 0 (no original suitable climate area) and 1 (suitable climate area unchanged).

We estimated sampling variances for both effect sizes FRS and FRA to determine the weight to be assigned during the meta-analysis. The calculation of sampling variances is provided in the Online Resource 1.

2.3 Harmonization of climate-change effects

All studies reported their baseline and projected climate conditions. Following Warren et al. (2011), we converted projected temperatures from the climate-change scenarios for each study to a common pre-industrial reference (approximately 1880) (Eq. 3). To this end, the assumed temperature increase between pre-industrial and the 1961–1990 climatic normal was 0.3 °C, between pre-industrial and 1981–1990 was 0.5 °C, and between pre-industrial and 1990 was 0.6 °C. These are the baseline conditions often reported by the selected studies (see Online Resource 2).

where GMTIn is global mean temperature increase converted to a common pre-industrial reference point for study n, Tscen is the projected temperature, and ∆Tpre-ref is the assumed temperature increase between the pre-industrial and the baseline conditions, which are both driven by (or based on) climate-change scenarios. We defined four intervals of temperature increase for the meta-analysis: 1–2 °C, 2–3 °C, 3–4 °C, and ≥ 4 °C. Temperature increases between 0 and 1 °C usually correspond to short-term climate-change scenarios depicting low carbon emissions and/or stringent mitigation policies.

2.4 Meta-analysis

We conducted a meta-analysis to derive the pooled effect for all effect sizes as a response to global mean temperature increase. We used the package “Metafor” in the R-3.2.2 software (Viechtbauer 2010) and the rma.mv() function assuming independence between the effect size and sampling variance. The included studies are a selection from a larger population of bioclimatic modeling studies (see Online Resource 2).

We ran mixed-effect models with random-effect structures (see Online Resource 1). We compared them using the Bayesian information criterion (BIC). We then fitted random-effect meta-models with restricted maximum likelihood (REML) to different taxa subsets. These are “all species,” “plants,” “vertebrates,” “birds,” “mammals,” “herptiles,” and “insects,” for the effect sizes FRS and FRA, and for all four intervals of global mean temperature increase. We introduced the variable “biomes” as a moderator to determine sources of heterogeneity (see Moderator Variable and Table OR1.1 in Online Resource 1).

For the meta-analyses and the meta-regression analyses ratios are often transformed using logit or log transformations to reach normality assumption for the effect sizes (Urban 2015; Benítez-López et al. 2017). We ran the mixed-effect models separately for the untransformed effect sizes FRS and FRA, the logit-transformed and the log10-transformed FRS and FRA, and checked the results for robustness (see Mixed-effect models in Online Resource 1). In addition, meta-regression analyses were used to relate pooled effect sizes FRS and FRA to global mean temperature increase.

We visually inspected the funnel plots of asymmetry to explore the possibility of publication bias (Viechtbauer 2010; Kuiper et al. 2014). We assessed heterogeneity by the formal test of heterogeneity “Q” (Borenstein et al. 2009; Viechtbauer 2010). Variability among the effect sizes was expected due to differential characteristics of the studies (e.g., different taxonomic groups, biomes, and temperature-change intervals).

3 Results

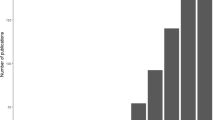

The systematic literature search yielded 302 relevant studies after the title screening. These studies were screened by abstract, out of which 138 fulfilled the criteria for full text screening. We finally selected 97 studies that assessed species composition of the originally occurring species at a location spanning publication dates between 1992 and 2015. Figure 2 shows the results from the systematic literature review. The selected studies allowed the calculation of 370 effect sizes for FRS (data from 60 studies) and 146 for FRA (data from 50 studies). The studies and the relevant information extracted are provided in the Online Resource 2. The types of bioclimatic models in the selected studies cover, in some cases, the entire distribution of each species studied. For instance, these models were derived for a continental species distribution or for endemic species. In other studies the models do not cover the entire range of all species and this likely slightly overestimates the effects of climate change.

The meta-analyses show similar results for untransformed, logit-transformed, and log-transformed effect sizes, suggesting robustness of these results. Here we present the results of log10-tranformed FRS and FRA, which is the most commonly used transformation. Results for untransformed effect sizes and logit-transformed FRS and FRA are provided in Tables OR3.5–OR3.8 in the Online Resource 3. We retained the random-effect structures (1 | Study ID + 1 | Extent) for the meta-analysis of FRS (BIC = − 502.4888) and (1 | Extent) for the meta-analysis of FRA (BIC = 14.8613) (see Table OR3.1 in Online Resource 3 for results of all random-effect structures).

Results from the meta-regressions to estimate the response changes of FRS and FRA to global mean temperature increase are shown in Fig. 3. The effect sizes decrease with increasing climate change—the rate of decrease is generally larger for FRA than for FRS.

Meta-regressions on global mean temperature increase for log10 effect sizes. a Fraction of remaining species and b fraction of remaining area with suitable climate. Confidence intervals (CI 95%) are shown by the shadowed line. Each effect size is represented by a circle, and the size of the circle indicates the number of species in the original study

Table 1 provides the results of the random-effect meta-models for FRS and FRA for all species. FRS and FRA were significantly lower under each global mean temperature increase interval. Overall, the FRS and FRA were reduced by 19% (95% confidence interval: 14–23%) and 47% (95% confidence interval: 37–55%), respectively (see Fig. OR3.1 Forest plots in Online Resource 3).

The first interval 1–2 °C for the all species group results in a FRS of 86% (95% confidence interval: 79–93%) and a FRA of 65% (95% confidence interval: 56–75%). These estimates imply that under a global mean temperature increase of up to 2 °C, terrestrial ecosystems could lose on average 14% of their current local species and that species could lose on average 35% of their suitable climate area. The intervals 2–3 °C and 3–4 °C result in larger reductions of FRS and FRA compared to the first interval: FRS is projected to reduce to 83% (95% confidence interval: 78–88%) and 78% (95% confidence interval: 72–86%), and FRA to 50% (95% confidence interval: 39–64%) and 46% (95% confidence interval: 34–63%), respectively. However, the largest reductions occur under a global mean temperature increase beyond 4 °C: only 68% of the local current species are projected to remain on average across the Earth’s terrestrial ecosystems (95% confidence interval: 57–80%) and their suitable climate area will likely be reduced to less than 46% (95% confidence interval: 25–85%). These responses are based on a wide range of climate projections with up to 6 °C increase in bioclimatic studies assessing distributions for birds and plants species (e.g., Shoo et al. 2005; Sekercioglu et al. 2008; Meyer et al. 2016).

FRS and FRA responses differ among taxonomic groups. The responses of the taxonomic group plants are lower than for vertebrates in all temperature-increase intervals (Fig. 4; see Table OR3.2 in Online Resource 3). In the interval of 1–2 °C, the fraction of local originally occurring plant species is reduced by 18%, whereas the vertebrate species fraction is reduced by 10%. Under a more extreme temperature-increase interval (e.g., 3–4 °C), the suitable climate area for plant species is reduced by 53% and for vertebrate species by 50%. These results differ significantly from the original situation (see values in Table 1). The visual inspection of the funnel plots of asymmetry for FRS and FRA (Fig. OR3.2 and Fig. OR.3.3 in Online Resource 3) indicates that a bias is absent.

Mixed-effect model results per taxonomic group plants and vertebrates for a fraction of remaining species and b fraction of remaining area with suitable climate. Whiskers indicate confidence intervals (CI 95%) and boxes demarcate standard errors. Top numbers indicate the number of studies (k) providing data for each group

We found that mammals show the largest reduction in FRS, which quickly declines beyond 2 °C. Contrary to this FRS case, FRA for birds reduces to a larger extent under all intervals (Fig. OR3.4 and Table OR3.3 in Online Resource 3).

Estimates of FRS and FRA can also be used to rank biomes to indicate sensitivities to climate change. The resulting effect-size estimates from our mixed-effect models were used to run meta-regressions to assess the response of biomes to global mean temperature increase (Fig. 5 and Fig. OR3.5 in Online Resource 3 for the FRA results). We found that deserts, temperate forests, and shrublands experience the largest reductions in FRS and tropical and boreal forests in FRA. These are thus likely the most sensitive biomes to increasing global temperatures.

Mixed-effect model—meta-regressions on global mean temperature increase for different terrestrial biomes. Circles indicate the log10 effect size fraction of remaining species, and the size of the circles corresponds to the number of species in the original study. Results obtained with meta-regression and 95% confidence

4 Discussion and conclusions

The projections of both the FRS and the FRA overall show continuous decreases. This indicates losses of local species richness (on average by 14% at 2 °C of global mean temperature increase) and losses of suitable climate area of many species (on average by 35% at 2 °C of global mean temperature increase). These results indicate that many species will be extirpated locally and disappear from areas where they now occur. This finding is supported by other studies (e.g., Wiens 2016) and will certainly challenge species conservation in many places (Johnson et al. 2017; Warren et al. 2018). However, this does not mean that total species richness will necessary decrease as new species can potentially expand their ranges and establish, depending on their ability to disperse (Hellmann et al. 2016), but such emerging species are logically ignored in our effect sizes.

We estimated that reductions exacerbate as global mean temperature goes beyond 2 °C. For example, at 3 °C of global mean temperature increase the local species richness decreased on average by 17% and the suitable climate area of species by 50%. In addition, these effects are expected not only to increase biodiversity losses but also to accelerate for every degree rise in global mean temperature. As a result, all the local decreases will likely lead to global extinctions.

The results of FRS and FRA vary among taxonomic groups and biomes. This means that the species responses are closely related to their individual sensitivities and exposures to changes in temperature (Urban et al. 2016). For example, the response of vertebrate species to increases in global mean temperature was a decrease in both FRS (on average 10% at 2 °C of global mean temperature increase) and FRA (on average 47% at 2 °C of global mean temperature increase). We found that within the vertebrate group, mammals are projected to undergo the largest local species reduction (i.e., overall FRS reduced by 22%). Our finding is consistent with previous studies (Pacifici et al. 2017), which conclude that many threatened mammals are also negatively affected by climate change. For plant species, the projected FRS and FRA decreased by 18% and 34%, respectively, at 2 °C of global mean temperature increase. The lower plant species’ FRS response probably resulted from a higher variability among effect sizes (Q test for heterogeneity in Table OR3.2 and funnel plots of asymmetry in Fig. OR3.1 in Online Resource 3) than the variability for vertebrate species’ FRS. This high variability likely relates to methodological issues (e.g., different modeling algorithms) that are inherent to bioclimatic modeling and that affect species-range shifts and abundances. Although exotic and aquatic species were excluded from our study, the different climate-change responses of these groups (e.g., Schnitzler et al. 2007; Kalwij et al. 2015) contribute to the challenge of setting a climate-protection target. Our analysis with the mixed-effect model with biomes as a moderator resulted in a lower heterogeneity in effect sizes compared to plants and vertebrate species. This indicates that biomes is an important explanatory variable when assessing the projected effect of global mean temperature increase on biodiversity.

FRS and FRA focus on assessing the remaining proportion of biodiversity under the conservative assumption of no dispersal. On average, no dispersal is close to reality for most species (Midgley et al. 2006; Hellmann et al. 2016). This implies that FRS and FRA generally indicate decreases. FRS is consistent with indices that estimate the naturalness or intactness, such as the BII (Scholes and Biggs 2005) or the MSA (Alkemade et al. 2009; Alkemade et al. 2011). As these indices are officially accepted by the Convention on Biologically Diversity to indicate the expected responses of original occurring species, our outcomes can also be used in international assessments of biodiversity change, such as the Global Biodiversity Outlook (sCBD 2014) and other global studies (e.g., PBL 2012; Kok et al. 2018). FRS, however, differs from other biodiversity indices, such as the Species Richness Index (Newbold et al. 2014), because FRS ignores new species for which the future climate becomes suitable. FRA accounts for suitable climate-area reduction of local species. Previous studies that analyzed suitable habitat of species to estimate global species richness patterns (e.g., Visconti et al. 2015) and/or the average proportional change in species distributions to estimate species extinction risks (e.g., Thomas et al. 2004) used similar approaches as our FRA. These studies inform developing goals for local biodiversity conservation and designing protected areas (Newbold et al. 2014; Virkkala et al. 2014). However, such studies also ignore reductions in areas with suitable climate of the originally occurring local species and the local community compositions.

Contrary to the instant loss of biodiversity caused by some non-climatic anthropogenic pressures, climate change triggers more gradual and long-term effects on species (Bertrand et al. 2011) and such temporal dynamics must be considered to interpret the FRS and FRA results. In this study, we estimated the effects of global mean temperature increase assuming that any increase materializes simultaneously, but in reality higher increases in temperature are projected to occur at the end of this century, whereas increases of 2 °C are possible already in 2050 (van Vuuren et al. 2011; IPCC 2013). Although our results support the notion that higher impacts of climate change will occur with higher temperatures, our results do not provide evidence that a climate target of keeping global temperature well below 2 °C protects biodiversity. Therefore, we support the pledge to keep climate change below 1.5 °C and preferably lower, as this helps to maintain the composition of local communities and their climatically suitable areas.

Understanding the climate-change impacts on biodiversity helps to prioritize biodiversity conservation strategies (Gärdenfors 2001; Broennimann et al. 2006). Our results generically relate climate change and biodiversity loss. This relationship is useful to assess relative adverse effects of different climate-change scenarios and to stress the importance of holding climate change well below 2 °C. Furthermore, our results can be used to explore interactions between climate change and other biodiversity-loss pressures, and estimate interactive effects. This implies that reducing the rate of biodiversity loss is critical and only possible if all pressures are reduced or eliminated (sCBD 2014). This means that it would be helpful if the UN Conventions on Biological Diversity and Climate Change closely collaborate to address multiple urgent environmental challenges.

References

Alkemade R, Bakkenes M, Eickhout B (2011) Towards a general relationship between climate change and biodiversity: an example for plant species in Europe. Reg Environ Chang 11:143–150. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-010-0161-1

Alkemade R, van Oorschot M, Miles L, Nellemann C, Bakkenes M, ten Brink B (2009) GLOBIO3: a framework to investigate options for reducing global terrestrial biodiversity loss. Ecosystems 12:374–390. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-009-9229-5

Bellard C, Bertelsmeier C, Leadley P, Thuiller W, Courchamp F (2012) Impacts of climate change on the future of biodiversity. Ecol Lett 15:365–377. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2011.01736.x

Benítez-López A, Alkemade R, Schipper AM, Ingram DJ, Verweij PA, Eikelboom JAJ, Huijbregts MAJ (2017) The impact of hunting on tropical mammal and bird populations. Science 356:180–183. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaj1891

Berry P, Ogawa-Onishi Y, McVey A (2013) The vulnerability of threatened species: adaptive capability and adaptation opportunity. Biology 2:872–893. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology2030872

Bertrand R et al (2011) Changes in plant community composition lag behind climate warming in lowland forests. Nature 479:517–520. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature10548

Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, Rothstein HR (2009) Introduction to meta-analysis. John Wiley & Sons, New York. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470743386

Box EO (1981) Macroclimate and plant forms: an introduction to predictive modeling in phytogeography. Dr. W. Junk Publishers, The Hague

Broennimann O, Thuiller W, Hughes G, Midgley GF, Alkemade J, Guisan A (2006) Do geographic distribution, niche property and life form explain plants’ vulnerability to global change? Glob Chang Biol 12:1079–1093. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2005.01157.x

Butchart SH et al (2010) Global biodiversity: indicators of recent declines. Science 328:1164–1168. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1187512

Cardinale BJ et al (2012) Biodiversity loss and its impact on humanity. Nature 486:59

CBD (2019) Biodiversity and the 2030 Agenda for sustainable development. Technical note. Secretariat of the convention on biological diversity, Montréal. doi:https://www.cbd.int/development/doc/biodiversity-2030-agenda-technical-note-en.pdf

CEE (2013) Guidelines for systematic review and evidence synthesis in environmental management. Version 4.2. Centre for Evidence-Based Conservation, Bangor University, UK. www.environmentalevidence.org/Documents/Guidelines/Guidelines4.2.pdf

Cook BI et al (2012) Sensitivity of spring phenology to warming across temporal and spatial climate gradients in two independent databases. Ecosystems 15:1283–1294. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-012-9584-5

Gärdenfors U (2001) Classifying threatened species at national versus global levels. Trends Ecol Evol 16:511–516. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0169-5347(01)02214-5

Guisan A, Zimmermann NE (2000) Predictive habitat distribution models in ecology. Ecol Model 135:147–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0304-3800(00)00354-9

Hellmann F, Alkemade R, Knol OM (2016) Dispersal based climate change sensitivity scores for European species. Ecol Indic 71:41–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2016.06.013

IPCC (2013) Climate change 2013: the physical science basis. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Johnson CN, Balmford A, Brook BW, Buettel JC, Galetti M, Guangchun L, Wilmshurst JM (2017) Biodiversity losses and conservation responses in the Anthropocene. Science 356:270–275. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aam9317

Kalwij JM, Robertson MP, van Rensburg BJ (2015) Annual monitoring reveals rapid upward movement of exotic plants in a montane ecosystem. Biol Invasions 17:3517–3529. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-015-0975-3

Kintisch E (2009) Projections of climate change go from bad to worse. Science 323:1546–1547. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.323.5921.1546

Kok MTJ et al (2018) Pathways for agriculture and forestry to contribute to terrestrial biodiversity conservation: a global scenario-study. Biol Conserv 221:137–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2018.03.003

Kuiper J, Janse J, Teurlincx S, Verhoeven J, Alkemade R (2014) The impact of river regulation on the biodiversity intactness of floodplain wetlands. Wetl Ecol Manag 22:647–658. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11273-014-9360-8

Leadley P et al (2014) Progress towards the Aichi biodiversity targets: an assessment of biodiversity trends, policy scenarios and key actions. Technical series 78. Secretariat of the convention on biological diversity, Montreal

Meyer SE, Leger EA, Eldon DR, Coleman CE (2016) Strong genetic differentiation in the invasive annual grass Bromus tectorum across the Mojave-Great Basin ecological transition zone. Biol Invasions 18:1611–1628. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-016-1105-6

Midgley G, Hughes G, Thuiller W, Rebelo A (2006) Migration rate limitations on climate change-induced range shifts in Cape Proteaceae. Divers Distrib 12:555–562. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1366-9516.2006.00273.x

Moss R et al (2010) The next generation of scenarios for climate change research and assessment. Nature 463:747–756. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature08823

Newbold T et al (2016) Has land use pushed terrestrial biodiversity beyond the planetary boundary? A global assessment. Science 353:288–291. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaf2201

Newbold T et al (2014) A global model of the response of tropical and sub-tropical forest biodiversity to anthropogenic pressures. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci 281:20141371. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2014.1371

Pacifici M et al (2015) Assessing species vulnerability to climate change. Nat Clim Chang 5:215–225. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2448

Pacifici M, Visconti P, Butchart SHM, Watson JEM, Cassola FM, Rondinini C (2017) Species’ traits influenced their response to recent climate change. Nat Clim Chang 7:205–208. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate3223

Parmesan C (2006) Ecological and evolutionary responses to recent climate change. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst 37:637–669. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.37.091305.110100

Parmesan C, Burrows MT, Duarte CM, Poloczanska ES, Richardson AJ, Schoeman DS, Singer MC (2013) Beyond climate change attribution in conservation and ecological research. Ecol Lett 16:58–71. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.12098

Parmesan C, Yohe G (2003) A globally coherent fingerprint of climate change impacts across natural systems. Nature 421:37–42. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature01286

PBL (2012) Roads from Rio+20. Pathways to achieve global sustainability goals by 2050. Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency, The Hague

Pearson RG, Dawson TP (2003) Predicting the impacts of climate change on the distribution of species: are bioclimate envelope models useful? Global Ecology and Biogeography 12:361–371. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1466-822X.2003.00042.x

Pearson RG et al (2006) Model-based uncertainty in species range prediction. J Biogeogr 33:1704–1711. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2699.2006.01460.x

Pecl G et al (2017) Biodiversity redistribution under climate change: impacts on ecosystems and human well-being. Science 355. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aai9214

Peñuelas J et al (2013) Evidence of current impact of climate change on life: a walk from genes to the biosphere. Glob Chang Biol 19:2303–2338. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.12143

Ripple WJ, Wolf C, Newsome TM, Hoffmann M, Wirsing AJ, McCauley DJ (2017) Extinction risk is most acute for the world’s largest and smallest vertebrates. Proc Natl Acad Sci. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1702078114

Rogelj J et al (2018) Scenarios towards limiting global mean temperature increase below 1.5 °C. Nat Clim Chang 8:325–332. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-018-0091-3

sCBD (2014) Global Biodiversity Outlook 4. Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity, Montréal

Schnitzler A, Hale BW, Alsum EM (2007) Examining native and exotic species diversity in European riparian forests. Biol Conserv 138:146–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2007.04.010

Scholes RJ, Biggs R (2005) A biodiversity intactness index. Nature 434:45–49. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature03289

Sekercioglu C, Schneider S, Fay J, Loarie S (2008) Climate change, elevational range shifts, and bird extinctions. Conserv Biol 22:140–150. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2007.00852.x

Shoo L, Williams S, Hero J (2005) Climate warming and the rainforest birds of the Australian wet tropics: using abundance data as a sensitive predictor of change in total population size. Biol Conserv 125:335–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2005.04.003

Thomas C et al (2004) Extinction risk from climate change. Nature 427:145–148. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature02121

Tittensor DP et al (2014) A mid-term analysis of progress toward international biodiversity targets. Science 346:241–244. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1257484

UNFCCC (2015) Adoption of the Paris Agreement. Report No. FCCC/CP/2015/L.9/Rev.1. UNFCCC, Bonn, http://unfccc.int/resource/docs/2015/cop21/eng/l09r01.pdf

Urban M (2015) Accelerating extinction risk from climate change. Science 348:571–573. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaa4984

Urban M et al (2016) Improving the forecast for biodiversity under climate change. Science 353. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aad8466

van Vuuren D et al (2011) The representative concentration pathways: an overview. Clim Chang 109:5–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-011-0148-z

Viechtbauer W (2010) Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. J Stat Softw 36(3):1–48. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v036.i03

Virkkala R, Poyry J, Heikkinen RK, Lehikoinen A, Valkama J (2014) Protected areas alleviate climate change effects on northern bird species of conservation concern. Ecology and Evolution 4:2991–3003. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.1162

Visconti P et al (2015) Projecting global biodiversity indicators under future development scenarios. Conserv Lett 9:5–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/conl.12159

Warren R, Price J, Fischlin A, de la Nava Santos S, Midgley G (2011) Increasing impacts of climate change upon ecosystems with increasing global mean temperature rise. Clim Chang 106:141–177. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-010-9923-5

Warren R, Price J, VanDerWal J, Cornelius S, Sohl H (2018) The implications of the United Nations Paris agreement on climate change for globally significant biodiversity areas. Clim Chang 147:395–409. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-018-2158-6

Warren R et al (2013) Quantifying the benefit of early climate change mitigation in avoiding biodiversity loss. Nat Clim Chang 3:678–682. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate1887

Wiens JJ (2016) Climate-related local extinctions are already widespread among plant and animal species. PLoS Biol 14:e2001104

Funding

Wageningen UR received funding for this work from the EU FP7 programme for the “Impacts and Risks from High-End Scenarios: Strategies for Innovative Solutions (IMPRESSIONS)” project (Grant Agreement No. 603416).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Nunez, S., Arets, E., Alkemade, R. et al. Assessing the impacts of climate change on biodiversity: is below 2 °C enough?. Climatic Change 154, 351–365 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-019-02420-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-019-02420-x