Abstract

The ecological impact of the dithiocarbamate fungicide metiram was studied in outdoor freshwater microcosms, consisting of 14 enclosures placed in an experimental ditch. The microcosms were treated three times (interval 7 days) with the formulated product BAS 222 28F (Polyram®). Intended metiram concentrations in the overlying water were 0, 4, 12, 36, 108 and 324 μg a.i./L. Responses of zooplankton, macroinvertebrates, phytoplankton, macrophytes, microbes and community metabolism endpoints were investigated. Dissipation half-life (DT50) of metiram was approximately 1–6 h in the water column of the microcosm test system and the metabolites formed were not persistent. Multivariate analysis indicated treatment-related effects on the zooplankton (NOECcommunity = 36 μg a.i./L). Consistent treatment-related effects on the phytoplankton and macroinvertebrate communities and on the sediment microbial community could not be demonstrated or were minor. There was no evidence that metiram affected the biomass, abundance or functioning of aquatic hyphomycetes on decomposing alder leaves. The most sensitive populations in the microcosms comprised representatives of Rotifera with a NOEC of 12 μg a.i./L on isolated sampling days and a NOEC of 36 μg a.i./L on consecutive samplings. At the highest treatment-level populations of Copepoda (zooplankton) and the blue-green alga Anabaena (phytoplankton) also showed a short-term decline on consecutive sampling days (NOEC = 108 μg a.i./L). Indirect effects in the form of short-term increases in the abundance of a few macroinvertebrate and several phytoplankton taxa were also observed. The overall community and population level no-observed-effect concentration (NOECmicrocosm) was 12–36 μg a.i./L. At higher treatment levels, including the test systems that received the highest dose, ecological recovery of affected measurement endpoints was fast (effect period < 8 weeks).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

This paper deals with the ecological impact of environmentally realistic concentrations of the dithiocarbamate fungicide metiram on freshwater organisms in outdoor freshwater microcosms. Despite the frequent use of fungicides to protect crops from fungal infections and the reported pollution of surface waters with these chemicals (e.g. Verro et al. 2009; Schäfer et al. 2011), relatively little experimental information is available on the ecological impact of realistic fungicide exposures on freshwater communities. The aquatic semi-field studies with fungicides published in the open literature are limited to chlorothalonil (Ernst et al. 1991), pentachlorophenol (e.g. Willis et al. 2004), carbendazim (Cuppen et al. 2000; Van den Brink et al. 2000; Slijkerman et al. 2004; Daam et al. 2009), triphenyltin (Roessink et al. 2006), fluazinam (Van Wijngaarden et al. 2010) and azoxystrobin (Gustafsson et al. 2010), illustrating the lack of open domain ecosystem-level information on effects of dithiocarbamates in edge-of-field surface waters.

The semi-field studies mentioned above focussed on measurement endpoints related to responses of primary producers and invertebrates, while treatment-related responses on aquatic fungi and bacteria hardly received attention. However, other ecotoxicological studies (also not including metiram) have demonstrated effects of fungicide exposure on aquatic fungi (e.g. Bundschuh et al. 2011; Dijksterhuis et al. 2011) and aquatic bacteria (e.g. Widenfalk et al. 2008; Milenkovski et al. 2010). Microbial communities are pivotal for the functioning of practically any ecosystem on Earth and that is why studying the potential effects of environmentally realistic pesticide exposures on the ecosystem services provided by microbes is important (Nienstedt et al. 2012). On the other hand, it is reported that functional redundancy and recovery potential of microbial communities may be high (Van den Brink et al. 2007). Here we begin to address this knowledge gap by investigating the effects of metiram on leaf litter breakdown and associated fungi (fungal biomass and hyphomycete abundance) and on the composition of the microbial community in the sediment compartment.

Formulated products of metiram have been used worldwide for over 40 years on a variety of fruits, vegetables, and ornamental crops to control fungal diseases like early blight, brown spot and black spot (McMullen and Jong 1971; Vawdrey et al. 2008; Horsfield et al. 2010). Metiram may unintentionally enter edge-of-field surface waters by, for example, spray drift. Metiram can be applied repeatedly (three up to nine times; minimum interval of 7 days) in crop protection programmes, potentially resulting in repeated short-term exposures in edge-of-field surface water of approximately 0.28–25 μg a.i./L (European Commission 2005; based on FOCUS calculations, personal communication with Peter Dohmen of BASF).

Acute laboratory toxicity data for standard and additional aquatic species and exposed to metiram demonstrate that the L(E)C50 values for fish, aquatic invertebrates and algae are 333–>20,000, 110–>1,000 and 63–>1,000 μg a.i./L, respectively (European Commission 2005). On average algae are more sensitive than aquatic invertebrates, but the difference in geometric mean L(E)C50 value for these taxonomic groups is less than a factor of 10. For metiram, Maltby et al. (2009) calculated a median HC5 (=hazardous concentration to 5 % of the tested species) of 40 μg a.i./L on basis of a species sensitivity distribution curve constructed with acute toxicity data for aquatic algae and aquatic invertebrates.

The aim of this paper is to evaluate the population and community level effects of realistic exposures of metiram in experimental freshwater ecosystems simulating the community of drainage ditches. This paper has its focus on treatment-related responses of zooplankton, macroinvertebrates, phytoplankton and microbes, as well as decomposition and community metabolism endpoints [e.g. dissolved oxygen (DO), pH].

Materials and methods

Test systems

The test was performed by using 14 enclosures (outdoor microcosms) situated in one of the experimental ditches located at the Sinderhoeve Experimental Station, Renkum, the Netherlands (Drent and Kersting 1993). Each enclosure consisted of a polycarbonate, translucent cylinder (diameter: 1.05 m; surface area 0.865 m2; height: 0.9 m), pushed approximately 0.15 m into the sandy loam sediment of the ditch. Water depth was approximately 0.5 m. The enclosures were installed into the experimental ditch on 16 July 2010, 25 days before start of the treatment. The enclosures simulated a shallow, mesotrophic, macrophyte-dominated freshwater community, but fish was not present. Shortly after placing the enclosures in the ditch, 30 individuals of Gammarus pulex and 28 individuals of Asellus aquaticus were introduced in each enclosure to ensure a more or less equal distribution in each test system. This was done since these macroinvertebrate shredders play an important role in the breakdown of leaf material. Both species are common in the experimental ditches of the Sinderhoeve Research Station, but their densities appeared to be low in the ditch selected for the experiment.

Fungicide treatment

Metiram was applied to enclosures as the formulated product BAS 222 28F (Polyram®) that was provided by BASF SE and had a measured active ingredient content of 70.39 % (w/w). The test substance was applied on the 10th, 17th and 24th of August, 2010 (interval 7 days) and the intended initial metiram concentrations in the overlying water of the enclosures were 0, 4, 12, 36, 108, and 324 μg a.i./L, in line with the expected population level effects on basis of single species toxicity tests and predicted environmental concentrations (PECs). The lowest test concentration is based on the reported 21-day NOEC of Daphnia magna (4.3 μg a.i./L) and the highest test concentration on the (lower) acute toxicity values reported for Tier-1 aquatic standard test species (see introduction section). Four test systems were used as controls and two test systems were used for each metiram concentration. Treatments and controls were assigned randomly to the 14 enclosures. The fungicide was applied by pouring approximately 2 L of dosing solution over the water surface and gently stirring to mix the compound in the water column. The control enclosures received water only.

Fungicide residues in water

Since metiram shows an extremely fast dissipation in water, actual peak concentrations were estimated by analyzing the metiram concentration of the dosing solutions and measuring the exact volume of dosing solution applied to each enclosure. In addition, 2 h after each application duplicate 500 mL depth-integrated samples were taken from each enclosure by means of a vacuum pump and stainless steel suction tubes and stored in borosilicate glass flasks. Metiram analysis of these water samples was performed at Alterra by liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometric detection by measuring the concentration of the ethylenebisdithiocarbamate (EBDC) ligand released in the water samples. The formed EBDC analyte was methylated with iodomethane. The methylated EBDC was then quantified by HPLC with MS/MS detection. The limit of quantification (LOQ) of the method for metiram analysis in water is 50 ng/L.

In addition, water samples collected on day 17 (3 days after the last metiram application) and on day 59 (end of experiment) from enclosures that received the three highest treatment levels were analysed by BASF SE for concentrations of metiram and its degradates ethylene–thiourea (ETU), ethylene–urea (EU), hydantoin (HY), carbamid, ethylene bisisothiocarbamate (EBIS) and C8H8N4S2 (TDIT). Before analysis of these compounds by means of LC/MS/MS, metiram water samples were methylated with iodomethane. Samples for the analysis of EBIS, carbamid and TDIT were acidified with formic acid, and samples for ETU, EU and HY measurements with acetic acid.

Ecological endpoints investigated

The endpoints measured in this study are summarized in Table 1. Artificial substrates, in the form of litter bags and pebble baskets, were used to monitor the macroinvertebrate community. Two litter bags (initially containing 2 g dry weight of Populus leaves) and two pebble baskets were incubated in the enclosures for approximately 2 weeks prior to sampling. For a detailed description of the artificial substrates and the collection of macroinvertebrates see Brock et al. (1992).

Approximately 10 L depth-integrated water samples were collected from each enclosure by means of a perspex tube to monitor the plankton community. A 5-L aliquot of each sample was filtered through a 55-μm mesh net and the collected zooplankton removed and preserved with acetate buffered lugol solution. The remaining 5-L aliquot of each sample was filtered through a 20-μm mesh net and the collected phytoplankton removed and also preserved with acetate buffered lugol solution. The filtered water was returned to its original enclosure. Cladocerans, ostracods and copepods were counted using a binocular microscope at a magnification of 25 times. Using an inverted microscope (100–400 times magnification), the numbers of rotifers and copepod nauplii were determined by counting the specimens in a known volume. Rotifers and cladocerans were identified to the lowest practical taxonomic level (in most cases species/genus level). Copepods (except nauplii) were divided into calanoids and cyclopoids.

Phytoplankton species composition was studied by counting the number of cells or colonies in a known volume of concentrated sample. Taxa and abundance measures were based on a maximum of 40 counting fields or a minimum of 200 observations (in at least 20 counting fields of a cuvette) using an inverted microscope (magnification ×400). Phytoplankton were identified to the lowest practical taxonomic level. Concentrations of total phytoplankton chlorophyll a were measured by means of a BBE AlgaeTorch (Envitech Ltd.). The measurements with this instrument are based on the natural fluorescence of algae cells as described for the BBE spectrofluorometric probe by Beutler et al. (2002). The BBE AlgaeTorch was placed in the bucket that contained 10 L of depth-integrated water sample from each enclosure and chlorophyll a measurements were performed at least three times in each sample.

Pre-application above-sediment macrophyte biomass was assessed by sampling three representative plots (0.25 m2) inside the study ditch but outside of the enclosures. The above-sediment macrophyte biomass was sampled from each enclosure at the end of the study. Sampled plant material was rinsed under tap water to remove loosely attached materials (e.g. sediment particles and invertebrates), packed in pre-weighted aluminium foil and dried in an oven for at least 48 h at 70 °C and until constant weight was reached.

Temperature, pH and DO were measured at approximately 25 cm water depth using an HQ40D (Hach) oxygen-acidity meter, equipped with a luminescent DO probe. Electrical conductivity was measured at the same water depth using a WTW LF191 meter and the alkalinity of a 100-mL unfiltered water sample from each enclosure was measured by titration with 0.02 N HCl to pH 4.2. Nutrient status was assessed by filtering a 100-mL depth integrated water sample through a GF/C glass fibre filter (mesh size 1.2 μm). The filtrate was stored in polyethylene flasks at −18 °C until analysis of total nitrogen, nitrate/nitrite, ammonium, ortho-phosphate and total phosphate following standard procedures.

Fungal biomass, aquatic hyphomycete abundance and leaf decomposition were assessed by deploying 5 or 8 g of air-dried alder leaf material in fine mesh (600 μm) or coarse mesh (0.5 cm × 0.5 cm) bags. The fine mesh excluded macroinvertebrates whereas the coarse mesh did not. Leaf material was conditioned in an experimental ditch for 4 weeks and allocated to the enclosures 4 days before the first fungicide application. Fifteen fine and 15 coarse mesh bags were initially placed in each enclosure and three bags of each type were retrieved on each sampling date. After retrieval, all leaf material was washed gently to remove attached sediment before processing.

Twenty-five 1-cm diameter alder leaf discs were cut per fine mesh bag; 10 discs being used for fungal identification and 15 discs for fungal biomass measurements. Conidial morphology was used to identify aquatic hyphomycetes (Ingold 1975) and leaf discs were agitated in sterile distilled water for 4 days prior to examination to stimulate sporulation. A measure of relative abundance was obtained by assigning species a score between 0 and 4 based on conidial abundance: 0 (conidia absent), 1 (1–3 conidia), 2 (4–9 conidia), 3 (10–15 conidia), 4 (>15 conidia). The remaining 15 leaf discs were placed in sterile eppendorf tubes and stored frozen until analysed for fungal biomass using an ergosterol assay modified from Newell and Fell (1992).

Alder leaf decomposition, expressed as mass loss, was determined for leaf material deployed in fine mesh bags (i.e. microbial decomposition) and coarse mesh bags (i.e. microbial decomposition + invertebrate consumption). Mass loss calculations took account of leaf material used for the assessment of fungal biomass and species identification.

In order to study the effects of metiram application on microbes in the sediment, three cores of the upper 3 cm of sediment (using a Perspex tune with an inner diameter of 2.4 cm) from each control enclosure and from those that received the two highest treatment levels (108 and 324 μg metiram/L) were collected on each sampling date (see Table 1). The three cores were thoroughly mixed in order to get one homogeneous sediment sample per test system. Subsequently, subsamples were taken and stored in eppendorf tubes, which were directly put on dry ice and later stored at −80 °C until use. Microbial community structure was assessed using molecular techniques (Bending et al. 2007; Ferreira et al. 2009; Tzeneva et al. 2008; Villeneuve et al. 2011). Total DNA was isolated from these subsamples using the FastDNA® Kit for Soil (MP Biomedicals, Santa Ana, CA) according to the manufacture’s protocol (Mincer et al. 2005). Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) (Mullis et al. 1986) amplifications were performed using the isolated DNA where the bacterial community was targeted by amplification of 16S rRNA gene fragments, whereas fungal community was targeted by both amplification of 18S rRNA gene fragments and internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region fragments, using the primers listed in Table 2. PCR products were analysed by denaturating gradient gel electrophoresis (DGGE) using a Dcode Universal Mutation Detection System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) (Muyzer et al. 1993). DGGE was performed on polyacrylamide gels with a denaturant gradient from 30 to 60 % for the separation of 16S rRNA gene amplicons, from 20 to 45 % for 18S rRNA gene amplicons and from 20 to 50 % for the ITS region (100 % denaturing acrylamide was defined as 7 M urea and 40 % (v/v) formamide). Aliquots of PCR products were loaded on the gel and electrophoresis was carried out with 1 × Tris-acetate-EDTA buffer at 60 °C and at 85 V for 16 h. After the completion of the electrophoresis, gels were silver-stained (Sanguinetti et al. 1994) and scanned. DGGE band detection and quantification of band intensity were performed using the Bionumerics software version 4.61 (Applied Maths, Belgium) (Tzeneva et al. 2009) and the results used to assess operational taxonomic units (OTUs) for microbes in the sediment samples (Massana and Jürgens 2003).

Statistics

Prior to statistical analysis, zooplankton, macroinvertebrate, phytoplankton, bacteria and fungi data were Ln(ax + 1) transformed, where x stands for the abundance value. For zooplankton a = 10, for macroinvertebrates a = 2, for phytoplankton a = 1.47, for bacteria a = 12.5 and for fungi a = 20. This was done to down-weigh high abundance values and to approximate a normal distribution for the data (for rationale see Van den Brink et al. 2000). NOEC calculations at taxon or parameter level (p ≤ 0.05) were carried out using the Williams test (ANOVA; Williams 1972). The analyses were performed with the Community Analysis computer program (Hommen et al. 1994).

Effects on the zooplankton, macroinvertebrate, phytoplankton, sediment bacterial and sediment fungal communities were analysed by the principle response curves (PRC) method (Van den Brink and Ter Braak 1999). In addition to the overall significance of the effects of the treatment regime (Monte Carlo permutation tests), each treatment was also compared to the controls to identify the NOEC at the community level. The NOEC calculations were carried out by applying the Williams test to the sample scores of the first principle component of each sampling date in turn (Van den Brink et al. 1996). Effects were considered consistent when they showed statistically significant deviations pointing in the same direction for at least two consecutive sampling points or occurred on a single sampling day during or immediately after the application period. The data were also evaluated for possible artefacts relating to small magnitude of measured counts, or having no treatment related concentration–response and/or no clear causality with community interactions or timing (European Commission 2002).

Results

Physico-chemical measurements

Water temperatures in the enclosures were approximately 18–19 °C at the start of the experiment and during the metiram application period. Temperatures gradually declined from sampling day 17 onwards and the lowest water temperature measured in the enclosures was approximately 12 °C. Data on weather conditions during the experiment can be found in the Supporting Information.

Statistically significant changes in physico-chemical endpoints are presented in Table 3 and temporal trends are presented in the Supporting Information. A significant, but small, treatment-related increase in electronic conductivity was observed at the highest treatment-level on the days 10 and 17. Control enclosure pH values ranged between 7.2 and 9.0 and pH of control enclosures were significantly lower than that of treatment enclosures in the pre-treatment period (day −1) and immediately after first metiram application (day 3). However, on sampling days 10, 17 and 48, pH values showed a small, but statistically significant, treatment-related decrease and on day 59 there was a significant increase in pH although all deviations were less than 1 pH unit.

DO concentrations were relatively low in all enclosures during the application period, but were always higher than 4 mg/L. After day 17, DO levels increased to approximately 10 mg/L. A small but significant decline in DO was observed on day 17 in the 324 μg a.i./L treatment, and on day 48 DO levels were significantly higher in all treated enclosures relative to controls. All treatment-related differences in DO concentration were less than 1–2 mg/L.

Alkalinity values in control enclosures ranged between 1.08 to 1.24 mmol/L. On day 17, a small but significant treatment-related increase in alkalinity was measured while at the end of the experiment (day 59) a small but significant treatment-related decrease was observed.

At the start and the end of the experiment, nitrate/nitrite, ammonium, ortho-phosphate and total phosphate concentrations in depth-integrated water samples from the enclosures were below detection limits. On days −1 and day 59 measured concentrations of total soluble nitrogen ranged between 0.9–1.1 and 0.4–0.7 mg/L, respectively. Treatment-related effects on nutrient concentrations in the water column could not be demonstrated.

Exposure concentrations

Metiram concentrations in the dosing solutions were on average 92.7 % of the intended concentration (range of 79.0–113.4 %), but concentrations in depth-integrated water samples collected approximately 2 h after the first fungicide application were only 36.6 % (range 16.0–65.1 %) of the initial concentration, highlighting the rapid disappearance of metiram from the water compartment. Unfortunately, the water samples collected 2 h after the second and third treatment were lost due to technical problems during metiram analysis (corrosion of the metal tubes of the measurement equipment).

Three days after the last application (day 17), the average concentration in water samples collected from the 324 μg metiram/L enclosures was 0.14 μg metiram/L (0.04 % of the initial concentration) and no metiram was detected in samples from the 108 and 36 μg metiram/L enclosures (<0.05 μg metiram/L). Average concentrations of the metabolites EU and ETU in day 17 water samples from the 324, 108 and 36 μg metiram/L enclosures, were 38.8 μg EU/L and 12.2 μg ETU/L, 15.6 μg EU/L and 0.6 μg ETU/L and 4.3 μg EU/L and 0.13 μg ETU/L, respectively. All other degradates analysed were below detection limits (i.e. <20 μg/L for HY; <0.2 μg/L for EBIS, carbimid and TDIT). At the end of the experiment (day 59 after the first treatment) the concentrations of metiram and all metabolites analysed were below detection limits (metiram < 0.05 μg/L; EU < 1.0 μg/L; HY < 20 μg/L; ETU, EBIS, carbimid and TDIT < 0.2 μg/L). These data illustrate that metiram dissipates very fast (estimated water dissipation DT50 of approximately 1–6 h) and that its metabolites are not persistent in the water compartment.

Zooplankton responses

Of the 30 zooplankton taxa collected during this study, 23 were rotifers, three were cladocerans, three were copepods and one was an ostracod. The most abundant zooplankton taxa in decreasing order were: Anuraeopsis fissa (Rotifera), copepod nauplii (Copepoda), Polyarthra remata (Rotifera), Trichocerca gr. similis (Rotifera), Keratella cochlearis (Rotifera), Lecane gr. luna (Rotifera), Cyclopoida (Copepoda), Ceriodaphnia sp. (Cladocera), Trichocerca gr. porcellus (Rotifera) and Squatinella rostrum (Rotifera). The number of zooplankton taxa was significantly reduced relative to controls at the highest dose (324 μg a.i./L) 10 days after the first application (Table 4). However, a statistically non-significant decline in zooplankton richness was observed in the post-exposure period (days 17–24) in the two highest doses (Fig. 1a).

Dynamics in taxa richness of zooplankton (a), macroinvertebrates (b), phytoplankton (c) and chlorophyll a biomass of phytoplankton (d) in the different treatments of the metiram enclosure experiment. The shaded area shows the range observed in control enclosures and the geometric mean values are presented per treatment. The vertical dotted lines indicate days of metiram application. The NOECs for treatment-related responses are presented in Tables 4, 5 and 6

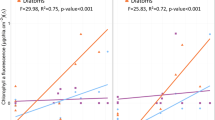

Multivariate PRC analysis indicated that the zooplankton community was significantly affected by exposure to metiram (Monte Carlo permutation test p = 0.009) with the rotifers Anureopsis fissa and P. remata being particularly negatively affected by the metiram application (Fig. 2a). Significant treatment-related effects on the zooplankton community were detected at the highest concentration (324 μg a.i./L) on day 3 and in the 108 and 324 μg a.i./L enclosures on days 10, 17 and 24 (Table 4).

Principal response curve diagram for the zooplankton dataset (a), the sediment bacteria DGGE band intensity dataset (b) and sediment bacteria OTUs dataset based on presence of DGGE bands (c) of the metiram enclosure study (for further explanation see description in text). The vertical dotted lines indicate days of metiram application. C dt canonical coefficient showing the difference between treatments and control in time, b k species weight that indicates the affinity of the taxon (a) or specific DGGE bands on the gels (b, c) with the PRC. The NOECs for treatment-related responses are presented in Tables 4 and 7. a 33 % of all variance could be attributed to sampling date (horizontal axis) and 31 % to treatment level, 34 % of which is displayed on the vertical axis. b 39 % of all variance could be attributed to sampling date and 21 % to treatment level, 17 % of which is displayed on the vertical axis. c 35 % of all variance could be attributed to sampling date and 23 % to treatment level, 17 % of which is displayed on the vertical axis

At the population level, statistically significant differences between treatments and controls could be observed for 13 of the 30 zooplankton taxa, but for two of them these differences occurred in the pre-treatment period (Table 4) and consequently were not treatment-related. Results of univariate analyses of population data (Williams test, p < 0.05) are presented in Table 4 and temporal trends illustrated in Fig. 3.

Dynamics in population abundance of zooplankton taxa (a–g) and of the phytoplankton taxon Anabaena sp. (h) in the different treatments of the metiram enclosure experiment. The shaded area shows the range observed in control enclosures and the geometric mean values are presented per treatment. a Total Rotifera, b A. fissa (Rotifera), c P. remata (Rotifera), d T. gr. similis (Rotifera), e total Copepoda, f Cyclopoida (Copepoda), g nauplii (Copepoda), h Anabaena sp. (Cyanophyta). The NOECs for treatment-related responses are presented in Tables 4 (zooplankton) and 6 (Anabaena sp.)

Treatment-related effects on Rotifera total abundance were observed at the two highest treatment-levels (NOEC = 36 μg a.i./L) and started soon after first application. Full recovery was observed on day 31 (Fig. 3a). Similar treatment-related declines were observed for A. fissa from day 3 to day 24 at the two highest treatment levels (NOECpopulation = 36 μg a.i./L). After day 31 densities in controls declined to zero and differences in abundance between treatments did not show a clear concentration–response relationship (Fig. 3b; Table 4). P. remata was the most sensitive rotifer species with minor but significant declines observed at the 36 μg a.i./L treatment level (days 3 and 24) and clear treatment-related declines observed from day 3 to day 31 at 108 and 324 μg a.i./L, followed by recovery. Note, however, that the decline in the 108 μg a.i./L enclosures was more pronounced than in enclosures that received 324 μg a.i./L (Fig. 3c; Table 4). The abundance of the rotifers T. gr. similis and K. cochlearis declined in the highest treatment level from day 3 to day 17 and in the 108 μg a.i./L enclosures on day 17. After day 17, abundance of T. gr. similis declined in all enclosures, including the controls (Fig. 3d; Table 4). Significant declines in the abundance of K. cochlearis were observed in the 36 μg a.i./L enclosures on day 24 (Table 4). Treatment-related declines in abundance of the rotifer Scaridium longicaudum were observed on day 10 (NOEC = 108 μg a.i./L), day 17 (NOEC = 36 μg a.i./L) and day 31 (NOEC = 108 μg a.i./L) and at the highest treatment level this species was not detected from day 10 to day 31, followed by recovery (Table 4).

Effects of metiram on Copepoda total abundance were consistent, but small. Statistically significant treatment-related declines in abundance were observed from day 3 up to day 24 and on day 48 (NOECs of 108 μg a.i./L, except on day 24 when a NOEC of 12 μg a.i./L was calculated) (Fig. 3e; Table 4). Treatment-related declines in Cyclopoida abundance were observed from day 3 to day 31 at the highest treatment level (NOEC = 108 μg a.i./L), except on day 17 when a NOEC of 36 μg a.i./L could be calculated. Full recovery of Cyclopoida was observed after day 31 (Fig. 3f; Table 4). Copepod nauplii were abundant in all enclosures and minor, but statistically significant, declines were observed at the highest concentration (NOEC = 108 μg a.i./L) on days 3, 10, 24 and 48. On day 24, the calculated NOEC was 12 μg a.i./L (Table 4).

Total abundance of Cladocera was not affected by metiram (Fig. 3g; Table 4) and the only treatment-related response observed was for Alona sp. on day 48 when a NOEC of 108 μg a.i./L could be calculated (Table 4). All other populations of Cladocera did not show a treatment-related response. Ostracoda occurred at low densities in all enclosures and a significant increase in abundance was observed (Table 4; NOEC = 108 μg a.i./L) on an single sampling date (day 17).

Macroinvertebrate responses

Sixty-three macroinvertebrate taxa were collected from the enclosures, the majority of which were Insecta (34 taxa), Mollusca (10), Oligochaeta (6), Hirudinea (5), Turbellaria (5), Crustacea (2) and Hydracarina (1). Several of these taxa occurred in low densities and/or were observed on a limited number of sampling dates only. The most abundant macroinvertebrate taxa in decreasing order were: Dero sp. (Oligochatea), Chaoborus sp. (Insecta), Chironomini (Insecta), Mesostoma sp. (Turbellaria), Lumbriculus sp. (Oligochaeta), Orthocladinae (Insecta), Ceratopogonidae (Insecta), Caenis sp. (Insecta), Zygoptera (Insecta) and Dugesia lugubris (Turbellaria).

A small decrease in the number of macroinvertebrate taxa relative to controls could be observed on day 15 (a day after the third metiram application) in the enclosures that received the highest concentration (324 μg a.i./L) (Fig. 1b; Table 5). Treatment-related effects of metiram on the macroinvertebrate community could not be demonstrated by means of multivariate PRC analysis (Monte Carlo permutation test p = 0.83). Although statistically significant differences between treatments and controls could be observed for 15 of the 63 macroinvertebrate taxa, these deviations predominantly occurred on isolated sampling days (Table 5). The only macroinvertebrate taxon for which statistical significant differences were observed on two consecutive samplings in the post-treatment period (days 43 and 57) was Dytiscidae larvae, but this taxon occurred in low densities (always <5 individuals per sample) and the effect concerned a treatment-related increase. For the ephemeropteran Caenis sp. and the mollusc Gyraulus crista, a statistically significant decline in numbers was calculated on day 15 (immediately after the third application), but densities of both taxa were low in all enclosures (Table 5).

Phytoplankton responses

One hundred and nine phytoplankton taxa were collected during this study, the majority of which were Chlorophyta (49 taxa), Desmidiaceae (23), Cyanophyta (14), Diatomeae (10), Euglenophyceae (7), Chrysophyceae (3), Dinoflagellata (2) and Cryptophyceae (1). A limited number of taxa dominated the phytoplankton community and many taxa occurred in low densities and/or were observed on a limited number of sampling dates only. The most abundant phytoplankton taxa in decreasing order were: Volvox (Chlorophyta), Scenedesmus arcuatus (Chlorophyta), Tetraedron minimum (Chlorophyta), Pennales (Diatomeae), Pseudanabaenaceae (Cyanophyta), Phacotus lendneri (Chlorophyta), Aphanocapsa (Cyanophyta), Anabaena (Cyanophyta), Oocystis (Chlorophyta) and Aphanothece (Cyanophyta).

A small decrease in the number of phytoplankton taxa relative to controls was observed on day 17 at the highest concentration (324 μg a.i./L) (Fig. 1c; Table 6). There was little evidence of a treatment-related response in total chlorophyll a biomass with significant reductions only observed on day 31 at the highest concentration (Fig. 1d; Table 6).

PRC analysis demonstrated that metiram treatment did not explain a significant component of the variation in phytoplankton community composition (Monte Carlo permutation test p = 0.544). Nevertheless, statistically significant treatment-related effects could be calculated for 42 of the 109 phytoplankton taxa (not including the abundance of main taxonomic groups), although the vast majority of these taxa (37 out of 42) showed a statistical significant response on an isolated sampling day only and mostly concerned low density taxa (<10 individuals/ml). In addition, statistically significant responses related to both decreases (15 cases) and increases (27 cases) in abundance and were mostly observed in the highest treatment only (NOEC of 108 μg a.i./L) (Table 6).

The blue-green alga Anabaena sp. (Fig. 3h) was one of the few phytoplankton taxa that showed a clear treatment-related decline in abundance on two consecutive sampling days (day 17 NOEC = 108 μg a.i./L and day 24 NOEC = 36 μg a.i./L), followed by recovery (Table 6).

In the Supporting Information more detailed information is provided on the treatment-related responses on total abundance of the main taxonomic groups of algae, and on abundance of individual phytoplankton taxa that showed a statistical deviation on at least two consecutive sampling days, or on a single sampling day during the application period (day 3–17).

Biomass of macrophytes

Prior to the metiram application the above-sediment macrophyte biomass was estimated to be 58.6 ± 13.4 g dry weight per enclosure (geomean ± SD; n = 3). At the end of the study the above-sediment macrophyte biomass in control enclosures had increased to 79.8 ± 6.8 g dry weight (geomean ± SD; n = 4), but no significant treatment-related effects on above-sediment biomass could be observed in the treated enclosures when compared to controls (also see Supporting Information).

Microbial endpoints and alder leaf decomposition

Based on conidia abundance, the dominant aquatic hyphomycetes on pre-conditioned alder leaf material were Angillospora longissima and Tetracladium setigerum. Whereas in controls the abundance score of A. longissima conidia generally increased during the course of the experiment (Fig. 4a), the abundance of T. setigerum conidia remained relatively low (Fig. 4b). For both species statistically significant treatment-related effects could not be demonstrated (William’s test, p > 0.05) despite the trend in lower abundance for T. setigerum in most enclosures that received metiram (Fig. 4b). A statistically significant effect of metiram on total fungal biomass (increase) associated with alder leaf litter could be observed on sampling day 3 only (William’s test, p < 0.05; NOEC 4 μg a.i./L; Table 7). This effect, however, did not show a clear concentration–response relationship (Fig. 4e). Mass loss of decomposing alder leaves increased during the experiment; mass loss in coarse mesh bags (Fig. 4c) increasing at a faster rate than mass loss in fine mesh bags (Fig. 4d). However, there was no significant treatment effect on mass loss in both types of litter bags (William’s test, p > 0.05).

Dynamics in conidia abundance scores of aquatic hyphomycetes, and alder leaf decomposition. The shaded area shows the range observed in control enclosures and the mean values are presented per treatment. a Conidia abundance score A. longissima, b conidia abundance score T. setigerum, c mass loss (g dry weight) of alder leaves in coarse mesh bags, d mass loss (g dry weight) of alder leaves in fine mesh bags, e fungal biomass (μg/mg) in decomposing alder leaves. The NOECs for treatment-related responses are presented in Table 7

PRC analysis indicated that sediment bacterial community structure differed significantly between control and metiram-treated enclosures whether expressed in terms of relative band density values of the DGGE profiles (Fig. 2b; Monte Carlo permutation test p < 0.05) or OTUs (Fig. 2c; Monte Carlo permutation test p < 0.05). Given that significant differences between control and treated enclosures were present pre-application (i.e. day −4, Table 7) they cannot be attributed to the metiram treatments. PRC analyses detected no significant effect of metiram application on the sediment fungal community structure (Monte Carlo permutation test p > 0.05).

Discussion

Dissipation of metiram

In our microcosm experiment, dissipation of metiram from the water compartment was fast (overall dissipation half-life 1–6 h) and the metabolites formed were not persistent. A laboratory DT50 of 0.7 days for metiram in water–sediment systems is reported (www.eu-footprint.org). Note that this DT50 should be interpreted with caution, since metiram is a polymer less soluble in water but disintegrating fast in this compartment. The fast dissipation of metiram from the water compartment is in accordance with results of Dutch chemical monitoring programmes. Metiram was hardly ever detected in surface waters despite its frequent use in the Netherlands (www.bestrijdingsmiddelenatlas.nl).

Responses of microbes

Despite being a fungicide, there was no evidence that metiram adversely affected the biomass, abundance or functioning of aquatic fungi. This may in part be due to the fact that the study was performed in a lentic system and aquatic fungi, in particular aquatic hyphomycetes, are more abundant and play a more important ecological role in lotic systems (Maltby 1992). The most likely explanation, however, is low exposure due to the fast dissipation of metiram in water. Note that on the plant surfaces of treated crops the exposure concentrations of metiram may be orders of magnitude higher than in the water column of our test systems.

Although on isolated sampling dates, minor differences on DGGE profiles (presence and absence of bands as well as intensity of bands) could be observed between sediment samples of controls and treated test systems, statistical analysis of the sediment microbial communities failed to show significant (fungi) or consistent (bacteria) effects of the metiram treatment. However, it is important to keep in mind the limitations of the PCR–DGGE technique in demonstrating treatment-related effects. Other studies revealed that bacterial populations that make up less than 1 % of the total community cannot be detected by PCR–DGGE (Muyzer et al. 1993; Murray et al. 1996), meaning that possible effects on low abundance populations could not be detected. However, an important question at stake is whether these low abundance populations are crucial for the ecosystem services provided. Another important limitation when dealing with a high number of samples is gel-to-gel variation, which can occur even with a well-established and standardized methodology (Powell et al. 2003; Nakatsu 2007). When dealing with complex and diverse microbial communities and a high number of samples, perfect alignment of obtained DGGE profiles is often laborious and difficult to obtain, which can mislead the analysis.

As already mentioned little information is available on the ecological impact of realistic dithiocarbamate fungicide exposures on freshwater microbial communities. Milenkovski et al. (2010) demonstrated effect of thiram and captan on denitrification, although at higher exposure concentrations (>2–3 mg a.i./L) than normally predicted for edge-of-field surface water due to normal agricultural use. Widenfalk et al. (2008) found that bacterial activity, and fungal and microbial biomass of a freshwater sediment were not affected by exposure to environmentally relevant concentrations of the fungicide captan. However, they observed significant shifts in the bacterial community composition using molecular techniques. In future studies, the use of more novel sequencing techniques may be necessary to get a better identification and understanding of the potential effects of environmentally realistic pesticide concentrations on microbial communities. For example, the combination of PCR–DGGE and sequencing techniques have been applied successfully to demonstrate impacts of different pesticides on soil microbial communities (Bending et al. 2007; Zhang et al. 2009). Furthermore, next generation sequencing-based approaches, such as 454 pyrosequencing analysis of barcoded PCR amplicons can provide information with respect to composition of microbial communities, including less abundant populations (Andersson et al. 2008; Lauber et al. 2009).

Threshold level for community and population effects

A summary of the treatment-related responses observed in our metiram enclosure experiment is provided in Table 8. In this table the treatment-related impacts on several endpoint categories are expressed in terms of Effect Classes (see European Commission 2002; Brock et al. 2006; De Jong et al. 2008). Of all endpoints investigated, the zooplankton community and several populations of Rotifera and Copepoda showed the clearest treatment-related response due to metiram application. The lowest-observed-effect concentration (LOEC) observed for the zooplankton community was 108 μg a.i./L (Effect class 3A), while at the population level the lowest LOEC for a treatment-related decline in abundance was 36 μg a.i./L. This LOEC, however, was observed on isolated sampling days only (Effect class 2, during application period; Effect class 1–2, after application period) and the LOECs for more prolonged effects were 108 μg a.i./L (Effect class 3A) for rotifer populations and 324 μg a.i./L (Effect class 3A) for the decline in Copepoda abundance. In contrast to zooplankton, consistent prolonged treatment-related effects on macroinvertebrate endpoints were only observed for Dytiscidae larvae (Insecta) at the end of the experiment (Effect class 3A–4; LOEC = 324 μg a.i./L). There was a small decline in phytoplankton taxon richness at the highest treatment level during the application period (Effect class 2) and treatment-related effects (increases and decreases in abundance) were observed for several phytoplankton taxa, although they were usually small in magnitude and/or observed on isolated sampling dates (Effect classes 1–2 or 2). The lowest LOEC for a phytoplankton taxon that showed a treatment-related decline on consecutive sampling days (Effect class 3A) was 324 μg a.i./L (Cyanophyta, Anabaena sp.). There was no evidence of treatment-related effects on macrophytes, leaf decomposition or microbial endpoints and hence the threshold level of effects based on the NOECs/LOECs of the most sensitive populations (Rotifera) in our metiram microcosm study is 12–36 μg a.i./L.

We are not aware of other aquatic micro/mesocosm experiments conducted with the fungicide metiram that have been published in the open literature, and thus allowing comparisons of population/community level effects with our study. However, micro/mesocosm experiments have been performed with other dithiocarbamate fungicides for regulatory purposes (not published in the open literature) in which Rotifera populations were also amongst the most sensitive populations. Aquatic model ecosystem experiments with other types of fungicides, such as carbendazim (Van den Brink et al. 2000), pentachlorophenol (Willis et al. 2004), triphenyltin (Roessink et al. 2006) and fluazinam (Van Wijngaarden et al. 2010) also demonstrated that Rotifera are relatively sensitive, but in these studies other groups of invertebrates (e.g. Copepoda, Cladocera, Turbellaria, Oligochaeta, Mollusca) were equally or somewhat more sensitive than rotifers. In contrast, Rotifera are hardly reduced in abundance by strobilurin fungicides (e.g. azoxystrobin; Gustafsson et al. 2010).

Comparison of microcosm and laboratory toxicity test results

For metiram, Maltby et al. (2009) calculated a median HC5 (=hazardous concentration to 5 % of the tested species) of 40 μg a.i./L on basis of a species sensitivity distribution curve constructed with acute toxicity data for aquatic algae and invertebrates. The ecological threshold level found in our metiram enclosure study is fully in accordance with the observation of Maltby et al. (2009) that population and ecosystem level effects in aquatic micro/mesocosms repeatedly exposed to a pesticide with high certainty do not occur at peak concentrations that are lower than the median acute HC5 divided by an assessment factor of 3. The database used by Maltby et al. (2009) on which this relationship between HC5 values and threshold values from micro/mesocosm experiments is based contains several insecticides, herbicides and fungicides, to which metiram can now be added.

Direct and indirect population-level effects and community metabolism endpoints

On basis of the available acute laboratory toxicity tests for aquatic organisms and metiram it was expected that populations of algae would be at least as sensitive than invertebrates (Maltby et al. 2009). In our study, however, zooplankton populations of Rotifera, and to a lesser extend Copepoda, were the most sensitive, while reductions in abundance of phytoplankton taxa were limited and less pronounced. In part this may be explained by the fact that the database of laboratory toxicity tests with aquatic invertebrates and metiram did not include Rotifera, but also the combination of rapid growth and recovery rates of algae and sampling frequency could have masked possible effects.

The short-term, but treatment-related decreases in several phytoplankton groups coupled with the small increase in electronic conductivity and alkalinity and the minor decrease in pH and DO during and/or immediately after the application period, suggest the occurrence of some treatment-related effects on primary producers. Effects of pesticides on the DO–pH–EC–Alkalinity syndrome via direct or indirect effects on the photosynthesis and metabolism of algae have been reported frequently (e.g. Brock et al. 1993; Van Wijngaarden et al. 2010). The fact that this treatment-related decrease in primary productivity did not cause prolonged treatment-related declines in abundance of phytoplankton populations may to some extent be explained by the compensation of reduced phytoplankton grazing by Rotifera and Copepoda (interplay of direct and indirect effects) or by the sublethal nature of the metiram effects on algae.

Compensation of direct toxic effects on phytoplankton due to toxicant-induced reduced grazing by zooplankton has been observed in aquatic model ecosystem experiments treated with other broad spectrum fungicides (e.g. Van den Brink et al. 2000; Roessink et al. 2006) and biocides (Fliedner et al. 1997; Jak et al. 1998) and in microcosms treated with an insecticide–herbicide mixture (Van den Brink et al. 2009). The observed short-term increases in population densities of several macroinvertebrate taxa in our microcosm experiment may also be due to shifts in species interactions caused by direct toxic effects of metiram. Indirect effects in toxicant-stressed aquatic micro-/mesocosms are reported to be more pronounced if the toxicant eliminates key species that do not recover rapidly, causing shifts in species interactions in the same (release of competition) or adjacent trophic level (release of grazing or predation) (see e.g. Baird et al. 2001; Fleeger et al. 2003; Relyea and Hoverman 2006; Clements and Rohr 2009). This apparently is not the case in our metriram enclosure study.

Ecological recovery

In our study we found fast recovery of all affected measurement endpoints (effect period < 8 weeks). According to Brock et al. (2008), and literature cited therein, recovery of affected populations from pesticide-stress in aquatic ecosystems may be rapid if the following conditions apply: the pesticide is not persistent and the exposure regime is short-term; the generation time of the populations affected is short; population reductions are only partial and/or pesticide-resistant life stages (e.g. eggs and ephyppia) are present (internal recovery); there is a ready supply of propagules of eliminated populations through active immigration by swimming or flying organisms or through passive immigration by e.g. wind and water transport (external recovery). Obvious explanations for the fast ecological recovery in our microcosm experiment are (1) the short-term exposure to metiram (overall dissipation DT50 1–6 h) despite its repeated application and (2) the short generation time of the sensitive populations affected. According to Barnthouse (2004) the reported mean generation time of Rotifera is 8 days with a range of 6 to 35 days.

Conclusions

In field enclosures that simulated an aquatic community of shallow drainage ditches, the dissipation of metiram from water was very fast (overall dissipation half-life 1–6 h). A few days after the third and last weekly metiram application (nominal concentrations of 4–324 μg a.i./L), the metabolites EU and ETU were measured in water above their detection limit, but these substances were not persistent. Amongst the large number of biological endpoints measured, the zooplankton community, and Rotifera populations in particular, showed clear treatment-related effects, followed by fast recovery (within 8 weeks after the first application). Treatment-related effects on phytoplankton and macroinvertebrates were minor and transient. There was no evidence that metiram application adversely affected alder leaf breakdown, fungal biomass and abundance of aquatic hyphomycetes on leaf litter. In addition, consistent treatment-related effects on the microbial community in the sediment compartment were not observed. The threshold level of effects based on the NOECs of the most sensitive populations (Rotifera) in our metiram microcosm study is 12–36 μg a.i./L.

References

Andersson AF, Lindberg M, Jakobsson H, Backhed F, Nyren P, Engstrand L (2008) Comparative analysis of human gut microbiota by barcoded pyrosequencing. PLoS One 3:e2836

Baird DJ, Brock TCM, De Ruiter PC, Boxall ABA, Culp JM, Eldridge P, Hommen U, Jak RG, Kidd KA, Dewitt T (2001) The food web approach in the environmental management of toxic substances. In: Baird DJ, Burton GA (eds) Ecological variability: separating natural from anthropogenic causes of ecosystem impairment. SETAC Press, Pensacola, pp 83–122

Barnthouse LW (2004) Quantifying population recovery rates for ecological risk assessment. Environ Toxicol Chem 23:500–508

Bending GD, Rodríguez-Cruz MS, Lincoln SD (2007) Fungicide impacts on microbial communities in soils with contrasting management histories. Chemosphere 69:82–88

Beutler M, Wiltshire KH, Meyer B, Moldaenke C, Lüring C, Meyerhöfer M, Hansen UP, Dau H (2002) A fluorometric method for the differentiation of algal populations in vivo and in situ. Photosynth Res 72:39–53

Brock TCM, Crum SJH, Van Wijngaarden RPA, Budde BJ, Tijink J, Zuppelli A, Leeuwangh P (1992) Fate and effects of the insecticide Dursban® 4E in indoor Elodea-dominated and macrophyte-free freshwater model ecosystems: I. Fate and primary effects of the active ingredient chlorpyrifos. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol 23:69–84

Brock TCM, Vet JJRM, Kerkhofs MJJ, Lijzen J, Van Zuilekom WJ, Gijlstra R (1993) Fate and effects of the insecticide Dursban® 4E in indoor Elodea-dominated and macrophyte-free freshwater model ecosystems: III. Aspects of ecosystem functioning. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol 25:160–169

Brock TCM, Arts GHP, Maltby L, Van den Brink PJ (2006) Aquatic risks of pesticides, ecological protection goals and common aims in EU legislation. Integr Environ Assess Manag 2:e20–e46

Brock TCM, Solomon KR, Van Wijngaarden RPA, Maltby L (2008) Temporal extrapolation in ecological effect assessment of chemicals. In: Solomon KR, Brock TCM, De Zwart D, Dyer SD, Posthuma L, Richards SM, Sanderson H, Sibley PK, Van den Brink PJ (eds) Extrapolation practice for ecotoxicological effect characterization of chemicals. SETAC Press & CRC Press, Boca Raton, pp 187–221

Bundschuh M, Zubrod JP, Kosol S, Maltby L, Stang C, Duester L, Schulz R (2011) Fungal composition on leaves explains pollutant-mediated indirect effects on amphipod feeding. Aquat Toxicol 104:32–37

Clements WH, Rohr JR (2009) Community responses to contaminants: using basic ecological principles to predict ecotoxicological effects. Environ Toxicol Chem 28:1789–1800

Cuppen JGM, Van den Brink PJ, Camps E, Uil KF, Brock TCM (2000) Impact of the fungicide carbendazim in freshwater microcosms. I. Water quality, breakdown of particulate organic matter and responses of macroinvertebrates. Aquat Toxicol 48:233–250

Daam MA, Satapornvanit K, Van den Brink PJ, Nogueiraa AJA (2009) Sensitivity of macroinvertebrates to carbendazim under semi-field conditions in Thailand: implications for the use of temperate toxicity data in a tropical risk assessment of fungicides. Chemosphere 74:1187–1194

De Jong FMW, Brock TCM, Foekema EM, Leeuwangh P (2008) Guidance for summarizing and evaluating aquatic micro- and mesocosm studies. RIVM Report 601506009, Bilthoven

Dijksterhuis J, Van Doorn T, Samson R, Postma J (2011) Effects of seven fungicides on non-target aquatic fungi. Water Air Soil Pollut. doi:10.1007/s11270-011-0836-3

Drent J, Kersting K (1993) Experimental ditches for research and natural conditions. Water Res 27:1497–1500

Ernst W, Doe K, Jonah P, Young J, Julien G, Hennigar P (1991) The toxicity of chlorothalonil to aquatic fauna and the impact of its operational use on a pond ecosystem. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol 21:1–9

European Commission (2002) Health & consumer protection directorate-general, 2002. Guidance document on aquatic ecotoxicology in the context of the directive 91/414/EEC, working document SANCO/3268/2001 rev.4 (final)

European Commission (2005) Health & consumer protection directorate-general, 2005. Review report for the active substance metiram. Finalised in the Standing Committee on the Food Chain and Animal health at its meeting on 3 June 2005 in view of the inclusion of metiram in Annex I of Directive 91/414/EEC, SANCO/4059/2001–rev3.3, 3 June 2005

Ferreira EPB, Dusi AN, Costa JR, Xavier GR, Rumjanek NG (2009) Assessing insecticide and fungicide effects on the culturable soil bacterial community by analyses of variance of their DGGE fingerprinting data. Eur J Soil Biol 45:466–472

Fleeger JW, Carman KR, Nisbet RM (2003) Indirect effects of contaminants in aquatic ecosystems. Sci Total Environ 317:207–233

Fliedner A, Remde A, Niemann R, Schäfers C, Stein B (1997) Effects of the organotin pesticide azoclotin in aquatic microcosms. Chemosphere 35:209–222

Gustafsson K, Blidberg E, Elfgren IK, Hellström A, Kylin H, Gorokhova E (2010) Direct and indirect effects of the fungicide azoxystrobin in outdoor brackish water microcosms. Ecotoxicology 19:431–444

Hommen U, Düllmer U, Vith D (1994) A computer program to evaluate plankton data from freshwater field tests. In: Hill IR, Heimbach F, Leeuwangh P, Matthiesen P (eds) Freshwater field tests for hazard assessment of chemicals. Lewis, Baca Raton, pp 503–513

Horsfield A, Wicks T, Davies K, Wilson D, Paton S (2010) Effect of fungicide use strategies on the control of early blight (Alternaria solani) and potato yield. Australas Plant Pathol 39:368–375

Ingold CT (1975) An illustrated guide to aquatic and water-borne hyphomycetes (fungi imperfecti) with notes on their biology. Freshwater Biological Association, Scientific Publication, 30, Ambleside

Jak RG, Ceulemans M, Scholten MCT, Van Straalen NM (1998) Effects of tributyltin on a coastal North Sea plankton community in enclosures. Environ Toxicol Chem 17:1840–1847

Lauber CL, Hamady M, Knight R, Fierer N (2009) Pyrosequencing-based assessment of soil pH as a predictor of soil bacterial community structure at the continental scale. Appl Environ Microbiol 75:5111–5120

Maltby L (1992) Detritus processing. In: Calow P, Petts GE (eds) The rivers handbook, vol 1. Blackwell Scientific, Oxford, pp 331–353

Maltby L, Brock TCM, Van den Brink PJ (2009) Fungicide risk assessment for aquatic ecosystems: importance of interspecific variation, toxic mode of action, and exposure regime. Environ Sci Technol 43:7556–7563

Massana R, Jürgens K (2003) Composition and population dynamics of planktonic bacteria and bacterivorous flagellates in seawater chemostat cultures. Aquat Microb Ecol 32:11–22

May LA, Smiley B, Schmidt MG (2001) Comparative denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis of fungal communities associated with whole plant corn silage. Can J Microbiol 47:829–841

McMullen RD, Jong C (1971) Dithiocarbamate fungicides for control of pear Psylla. J Econ Entomol 64:1266–1270

Milenkovski S, Bååth E, Lindgren P-E, Berglund O (2010) Toxicity of fungicides to natural bacterial communities in wetland water and sediment measured using leucine incorporation and potential denitrification. Ecotoxicology 19:285–294

Mincer TJ, Fenical W, Jensen PR (2005) Culture-dependent and culture-independent diversity within the obligate marine actinomycete genus Salinispora. Appl Environ Microbiol 71:7019–7028

Mullis K, Faloona F, Scharf S, Saiki R, Horn G, Erlich H (1986) Specific enzymatic amplification of DNA in vitro: the polymerase chain reaction. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol 51:263–273

Murray AE, Hollibaugh JT, Orrego C (1996) Phylogenetic compositions of bacterioplankton from two California estuaries compared by denaturing gradient electrophoresis of 16S rDNA fragments. Appl Environ Microbiol 62:2676–2680

Muyzer G, de Waal EC, Uitterlinden AG (1993) Profiling of complex microbial populations by denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis analysis of polymerase chain reaction-amplified genes coding for 16S rRNA. Appl Environ Microbiol 59:695–700

Nakatsu CH (2007) Soil microbial community analysis using denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis. Soil Sci Soc Am J 71:562–571

Newell SY, Fell JW (1992) Ergosterol content of living and submerged, decaying leaves and twigs of red mangrove. Can J Microbiol 38:979–982

Nienstedt KM et al (2012) Development of a framework based on an ecosystem services approach for deriving specific protection goals for environmental risk assessment of pesticides. Sci Total Environ 415:31–38

Nubel U, Engelen B, Felske A, Snaidr J, Wieshuber A, Amann RI, Ludwig W, Backhaus H (1996) Sequence heterogeneities of genes encoding 16S rRNAs in Paenibacillus polymyxa detected by temperature gradient gel electrophoresis. J Bacteriol 178:5636–5643

Powell SM, Bowman JP, Snape I, Stark JS (2003) Microbial community variation in pristine and polluted nearshore Antarctic sediments. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 45:135–145

Relyea R, Hoverman J (2006) Assessing the ecology in ecotoxicology: a review and synthesis in freshwater systems. Ecol Lett 9:1157–1171

Roessink I, Crum SJM, Bransen F, Van Leeuwen E, Van Kerkum F, Koelmans AA, Brock TCM (2006) Impact of triphenyltin-acetate in microcosms simulating floodplain lakes. I. Influence of sediment quality. Ecotoxicology 15:267–293

Sanguinetti CJ, Dias Neto E, Simpson AJ (1994) Rapid silver staining and recovery of PCR products separated on polyacrylamide gels. Biotechniques 17:914–921

Schäfer RB, Pettigrove V, Rose G, Allinson G, Wightwick A, Von der Ohe PC, Shimeta J, Kühne R, Kefford BJ (2011) Effects of pesticides monitored with three sampling methods in 24 sites on macroinvertebrates and microorganisms. Environ Sci Technol 45:1665–1672

Slijkerman DME, Baird DJ, Conrad A, Jak RG, Van Straalen NM (2004) Assessing structural and functional plankton responses to carbendazim toxicity. Environ Toxicol Chem 23:455–462

Tzeneva VA, Heilig HG, van Vliet WA, Akkermans AD, de Vos WM, Smidt H (2008) 16S rRNA targeted DGGE fingerprinting of microbial communities. Methods Mol Biol 410:335–449

Tzeneva VA, Salles JF, Naumova N, de Vos WM, Kuikman PJ, Dolfing J, Smidt H (2009) Effect of soil sample preservation, compared to the effect of other environmental variables, on bacterial and eukaryotic diversity. Res Microbiol 160:89–98

Van den Brink PJ, Ter Braak CJF (1999) Principal response curves: analysis of time-dependent multivariate responses of a biological community to stress. Environ Toxicol Chem 18:138–148

Van den Brink PJ, Van Wijngaarden RPA, Lucassen WGH, Brock TCM, Leeuwangh P (1996) Effects of the insecticide Dursban_4E (a.i. chlorpyrifos) in outdoor experimental ditches. II. Invertebrate community responses. Environ Toxicol Chem 15:1143–1153

Van den Brink PJ, Hattink J, Bransen F, Van Donk E, Brock TCM (2000) Impact of the fungicide carbedazim in freshwater microcosms. II. Zooplankton, primary producers and final conclusions. Aquat Toxicol 48:251–264

Van den Brink PJ, Maltby L, Wendt-Rasch L, Heimbach F, Peeters F (2007) New improvements in the aquatic ecological risk assessment of fungicidal pesticides and biocides. Society of Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, Brussels

Van den Brink PJ, Crum SJH, Gylstra R, Bransen F, Cuppen JGM, Brock TCM (2009) Effects of a herbicide-insecticide mixture in freshwater microcosms: risk assessment and ecological effect chain. Environ Pollut 157:237–249

Van Wijngaarden RPA, Arts GHP, Belgers JDM, Boonstra H, Roessink I, Schroer AFW, Brock TCM (2010) The species sensitivity distribution approach compared to a microcosm study: a case study with the fungicide fluazinam. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 73:109–122

Vawdrey LL, Grice KRE, Westerhuis D (2008) Field and laboratory evaluations of fungicides for the control of brown spot (Corynespora cassiicola) and black spot (Asperisporium caricae) of papaya in far north Queensland, Australia. Australas Plant Pathol 37:552–558

Verro R, Finizio A, Otto S, Vighi M (2009) Predicting pesticide environmental risk in intensive agricultural areas. I. Screening level risk assessment of individual chemicals in surface water. Environ Sci Technol 43:522–529

Villeneuve A, Montuelle B, Bouchez A (2011) Effects of flow regime and pesticides on periphytic communities: evolution and role of biodiversity. Aquat Toxicol 102:123–133

White TJ, Bruns T, Lee S, Taylor JW (1990) Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In: Innis MA, Gelfand DH, Sninsky JJ, White TJ (eds) PCR protocols: a guide to methods and applications. Academic Press, New York, pp 315–322

Widenfalk A, Bertilsson S, Sundh I, Goedkoop W (2008) Effects of pesticides on community composition and activity of sediment microbes—responses at various levels of microbial community organization. Environ Pollut 152:576–584

Williams DA (1972) The comparison of several dose levels with zero dose control. Biometrics 28:519–531

Willis KJ, Van den Brink PJ, Green JD (2004) Seasonal variation in plankton community responses of mesocosms dosed with pentachlorophenol. Ecotoxicology 13:707–720

Zhang B, Bai Z, Hoefel D, Tang L, Wang X, Li B, Li Z, Zhuang G (2009) The impacts of cypermethrin pesticide application on the non-target microbial community of the pepper plant phyllosphere. Sci Total Environ 407:1915–1922

Acknowledgments

The use of the research facilities and the research performed by Alterra employees was jointly funded by the Dutch Ministry of Economic Affairs, Agriculture & Innovation (research project BO-12.7-004-010) and BASF SE. The participation of Ronghua Lin was financially supported by the China Scholarship Council and Sujitra Kosol was in receipt of a scholarship from the Royal Thai Government (student reference ST_2481). Mauricio Rocha Dimitrov is supported through funding from the Strategic Research Fund of the WIMEK graduate school (project “Adaptive capacity and functionality of multitrophic aquatic ecosystems”).We would like to express our sincere gratitude to the following people that contributed to the experiment: Arrienne Matser, Steven Crum, Hans Zweers, Jan Bovenschen, Dick Belgers, Marie-Claire Boerwinkel, Caihong Yu, Paul van den Brink, Annelies J. Veraart, Sandro Sooß.

Conflict of interest

All authors, except Peter Dohmen, declare that they have no conflict of interest. Peter Dohmen is employee of BASF SE; BASF produces and markets the fungicidal active substance Metiram. The company is interested in learning all relevant facts on the environmental fate and effects of its products; such information is important for potential risk management and stewardship decisions.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Lin, R., Buijse, L., Dimitrov, M.R. et al. Effects of the fungicide metiram in outdoor freshwater microcosms: responses of invertebrates, primary producers and microbes. Ecotoxicology 21, 1550–1569 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10646-012-0909-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10646-012-0909-0