Abstract

Methane (CH4) emissions were compared for an intensively and extensively managed agricultural area on peat soils in the Netherlands to evaluate the effect of reduced management on the CH4 balance. Chamber measurements (photoacoustic methods) for CH4 were performed for a period of three years in the contributing landscape elements in the research sites. Various factors influencing CH4 emissions were evaluated and temperature of water and soil was found to be the main driver in both sites. For upscaling of CH4 fluxes to landscape scale, regression models were used which were specific for each of the contributing landforms. Ditches and bordering edges were emission hotspots and emitted together between 60% and 70% of the total terrestrial CH4 emissions. Annual terrestrial CH4 fluxes were estimated to be 203 (±48%), 162 (±60%) and 146 (±60%) kg CH4 ha−1 and 157 (±63%), 180 (±54%) and 163 (±59%) kg CH4 ha−1 in the intensively managed site and extensively managed site, for 2006, 2007 and 2008 respectively. About 70% of the CH4 was emitted in the summer period. Farm based emissions caused per year an additional 257 kg CH4 ha−1 and 172 kg CH4 ha−1 for the intensively managed site and extensively managed site, respectively. To further evaluate the effect of agricultural activity on the CH4 balance, the annual CH4 fluxes of the two managed sites were also compared to the emissions of a natural peat site with no management and high ground water levels. By comparing the terrestrial and additional farm based emissions of the three sites, we finally concluded that transformation of intensively managed agricultural land to nature development will lead to an increase in terrestrial CH4 emission, but will not by definition lead to a significant increase in CH4 emission when farm based emissions are included.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The assessment of the contribution of the trace gas methane (CH4) to the greenhouse gas effect and the related global warming is of great importance. Northern peatlands are significant sources of CH4, and are estimated to emit between 20 and 50 Tg yr−1 (Mikaloff Fletcher et al. 2004a, b). In northern oligotrophic and eutrophic managed peatland systems, net uptake and emission rates of CH4 have been found to depend on groundwater level, soil moisture content, temperature, and grassland management (Van den Pol-van Dasselaar et al. 1998a; Hargreaves and Fowler 1998; Christensen et al. 2003; Blodau and Moore 2003; Hendriks et al. 2007; Pelletier et al. 2007). CH4 emissions are difficult to estimate because of their large spatial and temporal variability (e.g. Smemo and Yavitt 2006). Therefore there are two major challenges when upscaling of CH4 fluxes from small scale to landscape scale: 1) selecting the correct ecosystem variables for stratification and 2) developing robust predictive relationships (Groffman et al. 2000).

The majority of fen meadow areas in Atlantic Europe are intensively managed. In the Netherlands, eutrophic peatlands have been drained for centuries and in the last 50 years peatlands have been drained even more deeply to make modern agriculture possible. These peatlands are therefore major carbon sources of CO2 as a result of peat oxidation (Langeveld et al. 1997; Veenendaal et al. 2007). Burgerhart (2001) has suggested that peat oxidation can be reduced if agricultural peatlands are transformed into wetland nature by raising the water table and by reducing agricultural intensity. These measures alter the carbon cycle and probably turn carbon sources into carbon sinks. Large uncertainties exist, however, of such measures on the CH4 balance. Hendriks et al. 2007 studied a nature restoration site with no agricultural practices since 1997. They found that a sink of 71 g CO2-equiv m−2 yr−1 had developed and they attributed this to a decrease in CO2 emissions from fields and an increase in CH4 emissions from ditches and waterlogged soil after stopping agricultural activity. However, in this case the previous situation for CH4 emission in the time that this area was used for intensive farming is unknown.

The objective of this study is 1) to find empirical relationships that describe the CH4 emissions from the different landscape elements and to provide a spatially integrated flux for the intensively managed and extensively managed area and 2) to investigate the influence of agricultural activity on the CH4 balance. Firstly, terrestrial methane fluxes were studied in an intensively managed area, where manure and fertiliser are applied and frequent mowing is practiced. These fluxes are compared to terrestrial CH4 fluxes measured in an extensively managed area with reduced agricultural activity. Secondly, farm based methane fluxes were estimated using an emissions factor approach. Methane fluxes of the two managed sites were compared to methane fluxes in a former agricultural site which was converted to a nature reserve 11 years ago by stopping intensive dairy farming, raising the water table (>20 cm below field level for most of the year) (Hendriks et al. 2007).

Experimental sites and methodology

Experimental sites

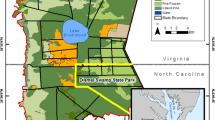

The experimental areas Oukoop, an intensively managed dairy farm and Stein, an extensively managed area are located in a polder in the western part of the Netherlands 52°02′01″N″ 04°46″E″ and 52°01′07″N″ 04°46″E″, respectively (Fig. 1). The climate is temperate and humid, with mean annual precipitation of about 800 mm and an annual long-term mean temperature of 9.8°C. Nol et al. (2008) estimated that 21% of the polder is open water (ditches and small permanent pools), 6% is ditch edges (waterlogged land bordering the ditches) and 73% is drier land with a fluctuating water table. The soils consist of a clayey peat or peaty clay top layer of about 25 cm overlying 12 m eutrophic peat deposits. The polder is between 1.6 and 1.8 m below sea level. Perched water tables occur after heavy rains, when the soil impedes water infiltration. Both sites have been described in more detail by Veenendaal et al. (2007) and Schrier-Uijl et al. (accepted, AFM).

The Oukoop experimental area is situated on an intensively managed dairy farm. The management regime varies, but on average consisted of mowing three to four times a year, whereas applications of manure and/or fertiliser took place 5–6 times a year. Lolium perenne is the most dominant species and Poa trivialis is co-dominant with no plants in the drainage ditches. On average the water table is being kept at 50 cm below the surface with perching water tables after heavy rain. Main characteristics of the Oukoop site are given in Table 1.

The management in Stein has been changed from intensive to extensive some 20 years ago and the area has been turned into a bird reserve. The research area was used as hayfield without application of manure and fertiliser during the measurement period and was mown three times each year after June 15 (2006, 2007 and 2008). The water table was adjusted since 2006, with a high water table (15–20 cm below the surface) in winter and a low water table in summer (50 cm below the surface). In Stein, Lolium perenne is also dominant, often with Poa trivialis co-dominant and no plants are present in the drainage ditches. Over time, Holcus lanatus, Anthoxanthum odoratum and Rumex acetosa have become more abundant. Characteristics of the Stein site are given in Table 1.

Methodology

Measurements

Terrestrial emissions of CH4 were determined using a closed chamber method (Hutchinson and Mosier 1981). Methane concentrations were measured using a Photo Acoustic Field Gas Monitor (INNOVA 1412 sn, 710-113, ENMO services, Belgium) connected by Teflon tubes to a PVC chamber (e.g. van Huissteden et al. 2005). Samples were taken from the headspace of a closed cylindrical, dark chamber (30 cm diameter, 25 cm height) that was placed on a collar. A small fan was installed in the chamber to homogenize the inside air and a water lock was placed to control inside pressure. On land we used water between the chamber and the collar to seal the chamber from the ambient air during the measurement. For the ditches we used floaters and a lever system to gently lower the chamber onto the water surface, carefully avoiding the effect of pressure differences and the disturbance of the water surface. We used external silica gel and soda lime filters to minimize cross-interference of CO2 and water vapour when CH4 was measured at high CO2 concentrations. The gas analyser was annually calibrated and tested for drift at the NMI (The Netherlands Institution of Standards, Delft, the Netherlands). In addition, the equipment was occasionally cross-checked for drift with a standard calibration gas. During the measurement period however, the equipment was not found to drift. All measurements were taken during the day, between 9am and 4pm. Each flux measurement consisted of five point-measurements taken at one-minute intervals from which dC/dt was calculated.

At the beginning of January 2005, 6 PVC collars (diameter 30 cm) were installed randomly in the footprint area of the eddy covariance systems at both experimental sites, so that gas emissions could be sampled. The measurements were carried out from January 2005 to November 2008 once a month up to twice a month or more during intensive field campaigns.

From February 2006 until November 2008, 19 additional sampling points, distributed over the experimental sites, were sampled every month at both research locations to study spatial variability. At both locations three landscape elements were distinguished with different soil/water temperatures and soil moisture conditions. They were: permanently water-filled ditches, ditch edges, and the field area with a fluctuating water table. Acreage of the landforms was determined by measurements in the field (Nol et al. 2008), the use of GIS maps and use of aerial photographs. In each of the two fields, four sample points were located on the water surface of the ditches, four points on the ditch edges and 11–14 sample points in the fields. In total over 1200 measurements were taken.

In addition to each flux measurement, soil or water temperature was measured at 5 cm depth and soil moisture content was determined in the top 5 cm of soil at the sample points, using a HH2 Delta-T device (Delta T Devices, Llandindrod Wells, USA) calibrated for the soil type. Soil and water temperatures were measured every half hour by sensors installed at a depth of 4 cm (Campbell scientific, USA and e+ sensor L-50, Eijkelkamp, the Netherlands, respectively). Water table depth was recorded hourly with pressure sensors installed in a steel frame to a depth of 70 cm into the soil at one or two places in the field (e+ sensor L-50, Eijkelkamp Agrisearch Equipment BV, Giesbeek, the Netherlands). In the ditch water of both experimental sites, electrical conductivity (EC) (Multi 350i, Fisher Scientific, the Netherlands) and pH (Cond340i-SET, Fisher Scientific, the Netherlands) was measured in 2008. In Stein, water tables were determined during each field CH4 measurement in 2008 at the location of the measurement.

Wind speed, air temperature and water vapour pressure were measured with an eddy covariance system consisting of a Campbell Csat C3 Sonic anemometer (Campbell Scientific, Logan, Utah, USA) directed into the main wind direction and a Licor 7500 open path Infrared gas analyser (LI-COR Lincoln, NE, USA). The height of the mast was 305 cm and was located in the middle of the field sample points in both areas (Veenendaal et al. 2007; Schrier-Uijl et al., accepted AFM). For continuous measurements of CH4 in the intensively managed site, we used the eddy covariance dataset of Kroon et al. (2007) where CH4 concentrations were measured with a system consisting of a three-dimensional sonic anemometer and a QCL spectrometer (model QCL-TILDAS-76, Aerodyne Research Inc., Billerica MA, USA).

Calculations and statistical analyses

Each flux measurement consisted of five points taken at one-minute intervals. The slope dC/dt of the gas concentration curve at time t = 0 s was estimated using linear regression and the slope-intercept method as described by Kroon et al. (2008). The average flux values for CH4 estimated by the slope intercept method were not significantly different from those estimated by the linear method and therefore, linear regression was used to calculate CH4 fluxes. The short measurement period of 240 seconds, the rejection of the last point in the case of levelling, and additional measures taken to prevent leakage, mixing and temperature artefacts made it possible to use linear regression (Schrier-Uijl et al., accepted AFM). First, the data quality was assessed: outliers resulting from disturbances, chamber leakage or instrument failures were removed from the data set. Annual mean net CH4 emissions were estimated by linear regression models of natural-logarithm transformed CH4 data using T soil /T water as explanatory variables (model-based approach, e.g. Hargreaves and Fowler 1998). The reliability of this model based approach has been tested previously for the Oukoop experimental site by performing a comparison of the chamber method measurements with eddy covariance measurements of CH4. The methods agreed well and the difference in cumulative emissions was 17% over a three months period (Schrier-Uijl et al. accepted AFM).

The statistical significance of differences between landscape elements within sites was calculated with one-way ANOVA. Analysis of covariance, with temperature as covariate, was used to ascertain the statistical significance of differences in the emissions from the landscape elements of the two sites. Correlations between natural-logarithm transformed CH4 emissions and independent variables were calculated using step-wise multiple linear regression analysis (case-wise elimination of variables). Paired T-tests were used to calculate the statistical difference in emission between sites at the same day. Uncertainties per landscape element were estimated with a temperature dependent approach and were weighted for the proportion of each landscape element in the total landscape. Statistical analyses were carried out with SPSS. For the calculations of the contribution of animals and manure in the total CH4 balance, we used the method as described by Hensen et al. (2006) which uses simple emission factors for dairy cows, heifers, calves, manure and farmyard manure.

Results

Landscape elements

We compared the landscape elements for the period that measurements of emissions from all landscape elements ran parallel (January 2006–December 2008). The average water table depth, water temperature and soil temperature during this period are shown in Fig. 2. Because temperatures of the two experimental areas are similar (within 0.5°C) for most of the time, only Stein is shown.

Monthly averaged water temperatures (green triangles) and soil temperatures (blue dots) at 4 cm depth in Stein (upper graph) and water table depths (lower graph) for the intensively managed (red squares) and extensively managed (blue dots) areas from month 1 (January 2006) to month 36 (December 2008)

At both sites, the CH4 emissions from the ditches (21% of the area) and ditch edges (6% of the area) were significantly higher than those from the fields (P < 0.01) and CH4 emissions from ditches were significantly higher that those from edges (P < 0.01). Ditches showed sometimes episodic, exceptionally high emission values. For example in 2006 on September 27 and 28 emissions were 366 (n = 6) and 123 (n = 4) mg m−2 hr−1 for the intensively managed and extensively managed areas, respectively versus 5 mg m−2 hr−1 averaged for the whole summer. During these extreme measurements wind velocity was high and turbulent water surface conditions were observed visually. Field fluxes in Stein were slightly higher compared to field fluxes in Oukoop, with maximum values of 22 and 19 mg m−2 hr−1, respectively. Field emission rates were highest in March, April, May and June in Oukoop and in May, June and July in Stein. Field fluxes were found to be increased by about 4% after manure application, which may cause the slightly higher emissions in March and April in Oukoop compared to Stein. Ditches and ditch edges together emit 60% and 68% of the total terrestrial emission in Stein and Oukoop, respectively (Fig. 3). Average flux values were not significantly different between Oukoop and Stein. In the ditch edges highest maximum values were observed in the spring period in Oukoop and in the summer period in Stein (365 and 118 mg m−2 hr−1, respectively), the difference between the average edge fluxes of the sites was not significant. At both sites in 2006, 2007 and 2008 ditch emission rates were highest in June, July, August and September with average summer fluxes of 25 and 31 mg m−2 hr−1 for Oukoop and Stein, respectively. Emission rates varied greatly depending on the time of the year and about 70% of the total annual CH4 emissions were observed in summer. Plant cover, composition and biomass in both areas were mostly similar, and field fluxes appeared not influenced by differences in vegetation.

Driving variables

Methane emission was found to be correlated with several parameters (Table 2), with temperature being to be the most important driver for CH4 emission in all three landscape elements for both Oukoop and Stein. When pooling water temperatures into classes, ln-transformed CH4 emissions (ln(CH4)) and water temperature in ditches showed a strong positive correlation in both sites (r 2 = 0.996; P < 0.01; and r 2 = 0.947; P < 0.01 for Oukoop and Stein, respectively; Fig. 4). The ln(CH4) emission in fields was strongly correlated with soil temperature (r 2 = 0.939; P < 0.01; and r 2 = 0.865; P < 0.01, for Oukoop and Stein respectively; Fig. 4). For ditch edges the r2 was 0.941 (P < 0.01) and 0.861 (P < 0.01) for Oukoop and Stein, respectively.

The dependency of ln transformed CH4 fluxes (mg m−2 hr−1) on temperature (°C) in ditches and fields in Oukoop (left) and Stein (right). Temperatures are pooled. The x-error bars represent the standard deviation of the temperature per class and the y-error bars represent the standard deviation of the ln(CH4) flux

Correlation of field CH4 emissions with soil moisture were significant (P < 0.05) in both the intensively and the extensively managed sites (Table 2), but when using non-linear multiple regression with temperature as explanatory variable, adding moisture did not significantly improve the predictive power of the regression equation. However, comparing monthly datasets revealed an exception for April in 2006 and 2007, when soil moisture was a stronger predictor than soil temperature for ln(CH4) at both sites. The water table did not show a correlation with ln(CH4) neither measured by eddy covariance in Oukoop nor measured by chambers in Stein (Table 2). Eddy covariance measurements show that after temperature correction variability in fluxes over the total area seem to be significantly correlated to wind velocity (Table 2). However, because fluxes measured by eddy covariance are integrated over a large area it is not clear if this dependence on turbulence appears in fields, edges, ditches or in a combination of these landscape elements. Ditch water temperature and electrical conductivity (EC) in Oukoop were positively correlated with ln(CH4) fluxes and pH was not (Table 2). Correlation statistics of chamber measurements (over three years) and eddy covariance measurements (over three months) are given in Table 2.

Water temperature was the main driving variable for CH4 emission in ditches and soil temperature in soils and therefore, water and soil temperature based regressions were used to estimate annual CH4 balances.

Annual terrestrial methane balances

To estimate annual terrestrial CH4 balances over 2006–2008, we used non-linear regression with temperature as explanatory variable

as described by Schrier et al. (accepted AFM) where F CH4 is the CH4 flux (mg m−2 hr−1) measured by the chamber, T is the temperature of soil or water (°C) and a and b are the coefficients which were derived for each landscape element using the measured temperatures and CH4 fluxes. Uncertainties in the chamber based regressions were temperature dependent and were different for Oukoop and Stein and for each landform. Average daily uncertainty was about ±60% of the average flux. To further evaluate the reliability of the use of day-time measurements for upscaling to 24-hour fluxes, diurnal variation of CH4 fluxes was tested using an independent continuous eddy covariance dataset of Kroon et al. (2007). Residual fluxes ln(F Res) (in mg m−2 hr−1) were determined after CH4 fluxes as measured by eddy covariance ln(F EC ) (in mg m−2 hr−1) were corrected for temperature dependency using

with a = −1.8, b = 0.17 and T soil = soil temperature (°C). The residual ln-fluxes were normally distributed (data not shown) and did not differ significantly between day and night (Fig. 5).

Day/night dynamics of CH4 fluxes represented by the residual fluxes ln(F Res ) after correction for temperature by \( \ln \left( {{F_{Res}}} \right) = \ln \left( {{F_{EC}}} \right) - \left( {a + b{T_{\text{soil}}}} \right) \) for October 2006 based on eddy covariance flux measurements given in Kroon et al. (2007). Error bars show the uncertainty in the mean residual CH4 flux given by \( {{2{\sigma_{\ln \left( {{F_{\text{res}}}} \right)}}} \mathord{\left/{\vphantom {{2{\sigma_{\ln \left( {{F_{\text{res}}}} \right)}}} {\sqrt n }}} \right.} {\sqrt n }} \) with σ the standard deviation

Half hourly soil temperature and water temperature data and equation 1 were used to estimate half hourly CH4 fluxes for Oukoop and Stein. Because fluxes were significantly different between the landforms, daily emissions were estimated per landscape element and multiplied by the area occupied by the landscape element, thus providing a spatially integrated daily flux (Fig. 6). Total terrestrial modelled fluxes ranged from 203 (±48%) to 146 (±60%) kg ha−1 yr−1 for Oukoop and from 180 (±54%) to 157 (±63%) kg CH4 ha−1 yr−1 for Stein. Methane fluxes did not differ significantly between Oukoop and Stein and did not differ significantly between years. Estimates of cumulative fluxes per site and per year are given in Table 3.

Time series of upscaled daily spatially integrated CH4 fluxes in Oukoop (left) and Stein (right) during the period 1 January 2006 to 31 December 2008. The temperature dependent uncertainty band around the dotted line represents plus and minus one standard error for mean prediction, based on the regression analyses, and calculated for each day

Discussion and conclusions

The objective of this research was to investigate the influence of reduced agricultural activity on the CH4 balance in two distinct areas. Therefore, the CH4 emission from a drained, intensively managed peat area was compared to the CH4 emission from a drained, extensively managed peat area.

First, the spatial and temporal variation of fluxes was investigated and a regression based approach was used to get spatially integrated annual CH4 emissions. Both areas were stratified into fields, ditches and ditch edges and in both sites the permanently water-filled, 30–60 cm deep ditches and ditch edges turned out to be CH4 hotspots that together emit 60% and 68% of the total terrestrial emission in Stein and Oukoop, respectively. Apparently, in the procedure of upscaling of the chamber based fluxes to landscape scale it is of great importance to determine the flux associated with each landscape element because they contribute significantly different to the CH4 balance.

The edges of the ditches were saturated for most of the year, with soil moisture contents >60%. These conditions can give rise to a differently vegetation than in the drier fields and in some places Iris pseudacorus and Typha angustifolia are present. These aerenchymatic plants may cause additional emissions in the edges because CH4 diffuses rapidly through their stems (e.g. Hendriks et al. 2007).

The CH4 emission rates from all three landscape elements vary seasonally. In the extensively managed site, high CH4 emissions were concentrated in the summer period, while in the intensively managed site they were concentrated in early spring and summer, partly associated with field applications of slurry. Van den Pol-van Dasselaar et al. (1999) also reported higher CH4 emissions after manure application suggesting the combination of higher temperatures in summer, wet soil, the application of easily decomposable organic material and the anaerobic conditions in the slurry as the reason for enhanced CH4 production. In both sites, over 70% of the total terrestrial CH4 flux is emitted in summer. The exceptionally high emission peaks from ditches (up to 800 mg m−2 hr−1 in the summer) may have resulted from ebullition events, during which CH4 quickly passes through the top layer in the water column. These events mainly occurred when both the water temperature and the wind velocity were high. Ebullition can play an important role during turbulent conditions when bubbles are triggered to escape from the ditch bottom and also low air pressure can cause an increase in ebullition (Hendriks et al. 2008). Besides, during turbulent conditions the aquatic boundary layer thickness is decreased and the potential diffusion rate increases (Kremer et al. 2003; Minkkinen and Laine 2006).

Because an integration-based approach may lead to overestimation due to exceptionally high emissions eg. in the summer months, a regression based approach was used to calculate annual CH4 fluxes (eg. Mikkelä et al. 1995; Chanton et al. 1995). Therefore, we aimed to find empirical relationships that describe the CH4 emissions from the landscape elements of the two drained peat areas and we found temperature to be the main driver. Except for temperature, no other measured variables did contribute significantly to the predictive power of the chamber based regression. Electrical conductivity was significantly correlated to CH4 emission from ditches, but to less data was available to include this in the regression. The only month for which we found a strong significant correlation between volume fraction of water in the soil and CH4 emission rates was April—the period when the field begins to dry out after being waterlogged in winter and when air temperature may rise rapidly from 10 to 25°C. Water table did not influence CH4 emissions significantly, but the highest emissions occurred at intermediate and sometimes high water tables. In the study areas the water table fluctuated seasonally and within seasons also due to rainfall and polder level regulation by the Dutch water board with high (−15 cm) average water table depths in winter and low (−50 cm) in summer in Stein. In Oukoop water tables depths were low (−65 cm) in summer and high (−20 cm) in winter, and in the winter period perched water tables occurred after heavy rains. Most strong correlations between water table and CH4 emission in other studies have been found at water tables between 0 and 20 cm below field level (eg. Furukawa et al. 2005; Hargreaves and Fowler 1998; Strack et al. 2004). The mostly lower water table (>20 cm below field level) in our site could be the cause for the lack of correlation between water table and CH4 emission.

Eddy covariance measurements showed that no significant differences in CH4 flux occurred between day and night after correction for temperature. Thus, empirical relations based on temperature can be used to predict 24-hour fluxes of CH4 per landscape element. The predictions of monthly to annual CH4 emission have found to be in good agreement with values as measured by eddy covariance (Schrier et al, accepted AFM). However, considering the daily variability in CH4 fluxes a better understanding of the influence of variables such as wind, precipitation, air pressure and application of manure and fertiliser on CH4 emission is needed.

The measurements showed that both areas in this study are a net terrestrial source of CH4 with annual regression-based means ranging from 146 to 203 kg ha−1 for Oukoop and from 156 to 180 kg ha−1 for Stein. These values are compared to emissions found in other managed and unmanaged peatland ecosystems (Table 4). Van den Pol-van Dasselaar et al. (1998a) studied CH4 emissions in peat soils in a nature reserve elsewhere in the Netherlands and reported also a large spatial variability. Though the emission values in fields were quite similar to ours, the emission rates they found in saturated land were higher.

The field fluxes found in this study (water tables of 20–60 cm below field level) are lower compared to fluxes found in some other eutrophic systems with water tables between 0 and 20 cm below field level for most of the year (eg. Bellisario et al. 1999; Hendriks et al. 2007; Furukawa et al. 2005; Hargreaves and Fowler 1998; Strack et al. 2004). The extremely high emission rates from ditches found by Minkkinen and Laine (2006) and by Bubier et al. (1993) were similar to the extreme values we found at turbulent water conditions in summer, but average summer fluxes of 18.72 mg m2 hr−1 were higher.

The total ecosystem CH4 emissions for both areas includes besides the terrestrial emissions also emissions from the farm itself. We estimated the total farm emissions (Q) for the farm located in the Oukoop area using a general accepted emission factor approach as described by Hensen et al. (2006) by

with N the number of animals and with emission factors for dairy cows (E d ), heifer (E y ), calves (E c ), manure (E m ) and farmyard manure (E f ): 274, 170, 48, 53 and 40 g CH4 day−1 animal−1 or m−3 for farm yard manure, respectively (Sneath et al. 2006; van Amstel et al. 2003).

The Oukoop farm owned during the measurement period 50 ha land with 65 adult cows, 20 heifer, 10 calves and had a storage of 700 m3 slurry and no other farm yard manure. The total farm emissions were estimated at 429 kg CH4 ha −1 yr−1. In addition, this farm used about 20 ha extra land in the Stein area for grass production. The grass is being removed to feed cows in the Oukoop area, and thus the estimated total farm emissions have to be distributed by approximately 0.4 and 0.6 over the extensively managed area and the intensively managed area, respectively. The mean total CH4 emissions (terrestrial + farm based) for Oukoop and Stein are given in Table 5.

To investigate the influence of agricultural activity on the CH4 balance, CH4 fluxes of our two managed sites were also compared to a former agricultural peat site which was converted to a nature reserve 11 years ago by raising the water table (>20 cm below field level for most of the year) and cessation of any agricultural management (Hendriks et al. 2007). Without farm based emissions, the intensively managed area and extensively managed area are a net source of CH4 ranging from 146 to 203 kg ha−1 and from 156 to 180 kg ha−1, respectively and the natural site is a larger source of 417 kg ha−1. When we took account of the farm-based emissions, the estimated total annual CH4 flux was 427 kg ha−1 in the intensively managed site and 339 kg ha−1 in the extensively managed site averaged over the three years compared to 417 kg ha−1 in the natural site of Hendriks et al. (2007). This suggests that transformation of intensively managed agricultural land to nature development will lead to an increase in terrestrial CH4 emission, but not by definition lead to a significant increase in CH4 emission when farm based emissions are included.

References

Adrian NR, Robinson JA, Suflita JM (1994) Spatial variability in biodegradation rates as evidenced by methane production from an aquifer. Appl Environ Microbiol 60:3632–3639

Bellisario LM, Bubier JL, Moore TR, Chanton JP (1999) Controls on CH4 emissions from a northern peatland. Global Biogeochem Cycles 13:81–91

Blodau C, Moore TR (2003) Experimental response of peatland carbon dynamics to a water table fluctuation. Aquat Sci 65:47–62

Bubier J, Costello A, Moore TR, Roulet NT, Savage K (1993) Microtopography and methane flux in boreal peatlands, northern Ontario, Canada. Can J Bot-Revue Canadienne De Botanique 71:1056–1063

Burgerhart N (2001) Mogelijkheden voor koolstofopslag in Nederlandse ecosystemen, Dutch National Inventory Report for LULUCF sector, category 5D1

Chanton JP, Whiting GJ, Happell JD, Gerard G (1993) Contrasting rates and diurnal patterns of methane emission from emergent aquatic macrophytes. Aquat Bot 46:111–128

Christensen TR, Ekberg A, Strom L, Mastepanov M, Panikov N, Mats O, Svensson BH, Nykanen H, Martikainen PJ, Oskarsson H (2003) Factors controlling large scale variations in methane emissions from wetlands. Geophys Res Lett 30(7):1414

Furukawa Y, Inubushi K, Ali M, Itang AM, Tsuruta H (2005) Effect of changing groundwater levels caused by land-use changes on greenhouse gas fluxes from tropical peat lands. Nutr Cycl Agroecosyst 71:81–91

Groffman PM, Brumme R, Butterbach-Bahl K, Dobbie KE, Mosier AK, Ojima D, Papen H, Parton WJ, Smith KA, Wagner-Riddle C (2000) Evaluating annual nitrous oxide emissions at the ecosystem scale. Global Biogeochem Cycles 14:1061–1070

Hamilton JD, Kelly CA, Rudd JWM, Hesslein RH, Roulet NT (1994) Flux to the atmosphere of CH4 and CO2 from wetland ponds on the hudson-bay lowlands (hbls). J Geophys Res-Atmos 99:1495–1510

Hargreaves KJ, Fowler D (1998) Quantifying the effects of water table and soil temperature on the emission of methane from peat wetland at the field scale. Atmos Environ 32:3275–3282

Hendriks DMD, van Huissteden J, Dolman AJ, van der Molen MK (2007) The full greenhouse gas balance of an abandoned peat meadow. Biogeosciences 4:411–424

Hendriks DMD, Dolman AJ, van der Molen MK, van Huissteden J (2008) A compact and stable eddy covariance set-up for methane measurements using off-axis integrated cavity output spectroscopy. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 8(2):431–443

Hensen A, Groot TT, Van den Bulk WCM, Vermeulen AT, Olesen JE, Schelde K (2006) Dairy farm CH4 and N2O emissions, from one square meter scale to the full farm scale. Agric Ecosyst Environ 112(2–3):146–152

Hutchinson GL, Mosier AR (1981) Improved soil cover method for field measurement of nitrous-oxide fluxes. Soil Sci Soc Am J 45(2):311–316

Huttunen JT, Nykanen H, Turunen J, Martikainen PJ (2003) Methane emissions from natural peatlands in the northern boreal zone in finland, fennoscandia. Atmos Environ 37:147–151

Kroon PS, Hensen A, Jonker HJJ, Zahniser MS, van ’t Veen WH, Vermeulen AT (2007) Suitability of quantum cascade laser spectroscopy for CH4 and N2O eddy covariance flux measurements. BG 4:715–728

Kroon PS, Hensen A, van den Bulk WCM, Jongejan PAC, Vermeulen AT (2008) The importance of reducing the systematic error due to non-linearity in N2O flux measurements by static chambers. Nutr Cycl Agroecosyst 82(2):175–186

Kremer JN, Reischauer A, D’Avanzo C (2003) Estuary-specific variation in the air-water gas exchange coefficient for oxygen. ESTUARIES 26(4a):829–836

Langeveld CA, Segers R, Dirks BOM, van den Polvan Dasselaar A, Velthof GL, Hensen A (1997) Emissions of CO2, CH4 and N2O from pasture on drained peat soils in the Netherlands. Eur J Agron 7(1–3):35–42

Liblik LK, Moore TR, Bubier JL, Robinson SD (1997) Methane emissions from wetlands in the zone of discontinuous permafrost: Fort simpson, northwest territories, Canada. Global Biogeochem Cycles 11:485–494

Mikaloff Fletcher SE, Tans PP, Bruhwiler LM, Miller JB, Heimann M (2004a) CH4 sources estimated from atmospheric observations of CH4 and 13C/12C isotopic ratios: 1. Inverse modeling of source processes. Glob Biogeochem Cycles 18(4), doi:10.1029/2004GB002223

Mikaloff Fletcher SE, Tans PP, Bruhwiler LM, Miller JB, Heimann M (2004b) CH4 sources estimated from atmospheric observations of ch4 and 13C/ 12C isotopic ratios: 2. Inverse modeling of CH4 emissions from geographical regions. Glob Biogeochem Cycles, 18

Mikkelä C, Sundh I, Svensson BH, Nilsson M (1995) Diurnal variation in methane emission in relation to the water table, soil temperature, climate and vegetation cover in a Swedish acid mire. Biogeochemistry 28(2):93–114

Minkkinen K, Laine J (2006) Vegetation heterogeneity and ditches create spatial variability in methane emissions from peatlands drained for forestry. Plant Soil 285:289–304

Nol L, Verburg PH, Heuvelink GBM, Molenaar K (2008) Effect of land cover data on nitrous oxide inventory in fen meadows. J Environ Qual 37:1209–1219

Pelletier L, Moore TR, Roulet NT, Garneau M, Beaulieu-Audy V (2007) Methane emissions from three peatlands in the La Grande Riviera watershed, James Bay lowland, Canada. J Geophys Res-Biogeosci, 112, noG1, Note(s): G01018.1-G01018.12] (3/4 p)

Smemo KA, Yavitt JB (2006) A multi-year perspective on methane cycling in a shallow peat fen in central New York State, USA. Wetlands 26(1):20–29

Sneath W, Beline F, Hilhorst A, Peu P (2006) Monitoring GHG from manure stores on organic and conventional dairy farms. Agric Ecosyst Environ 112:122–128

Strack M, Waddington JM, Tuittila ES (2004) Effect of water table drawdown on northern peatland methane dynamics: Implications for climate change. Global Biochemical Cycles, doi:10.1029/2003GB002209

Van Amstel A, Kroeze C, van Eerdt M, Dumont M, Both D (2003) National emissions of methane and nitrous oxide from agriculture in The Netherlands: current estimates and future trends, Workshop on Inventories and projections of greenhouse gas and ammonia emissions from agriculture, 27–28 February 2003, European Environmental Agency, Copenhagen

van den Pol-van Dasselaar A, Corre WJ, Prieme A, Klemedtsson AK, Weslien P, Stein A, Klemedtsson L, Oenema O (1998a) Spatial variability of methane, nitrous oxide, and carbon dioxide emissions from drained grasslands. Soil Sci Soc Am J 62:810–817

van den Pol-van Dasselaar A, van Beusichem ML, Oenema O (1998b) Effects of soil moisture content and temperature on methane uptake by grasslands on sandy soils. Plant Soil 204:213–222

van den Pol-van Dasselaar A, Van Beusichem ML, Oenema O (1999) Methane emissions from wet grasslands on peat soil in a nature preserve. Biogeochemistry 44:205–220

van Huissteden J, Maximov TC, Dolman AJ (2005) High methane flux from an arctic floodplain (Indigirka lowlands, eastern Siberia). J Geophys Res-Biogeosci 110(G2):G02002

Veenendaal EM, Kolle O, Leffelaar PA, Schrier-Uijl AP, Van Huissteden J, van Walsem J, Möller F, Berendse F (2007) CO2 exchange and carbon balance in two grassland sites on eutrophic drained peat soils. Biogeosciences 4:1027–1040

Waddington JM, Day SM (2007) Methane emissions from a peatland following restoration, J Geophys Res-Biogeosci, doi:10.1029/2007JG000400

Acknowledgements

This research project was funded by Wageningen University, The Province of North Holland, CarboEurope IP (contract number: GOCE-CT-2003-505572) and the Dutch National Research Programme Climate Changes Spatial Planning (www.klimaatvoorruimte.nl). Many thanks are due to Jan van Walsem and Frans Möller for their help in the field and in the lab and to the van Eijk and van Eeuwijk families for their logistical support. We are grateful to the State Forestry Service for access to the site and to Nico de Bruin for his collaboration. J. Burrough advised on the English and E.J. Bakker advised on the statistical analyses.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Responsible editor: Klaus Butterbach-Bahl.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Schrier-Uijl, A.P., Kroon, P.S., Leffelaar, P.A. et al. Methane emissions in two drained peat agro-ecosystems with high and low agricultural intensity. Plant Soil 329, 509–520 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-009-0180-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-009-0180-1